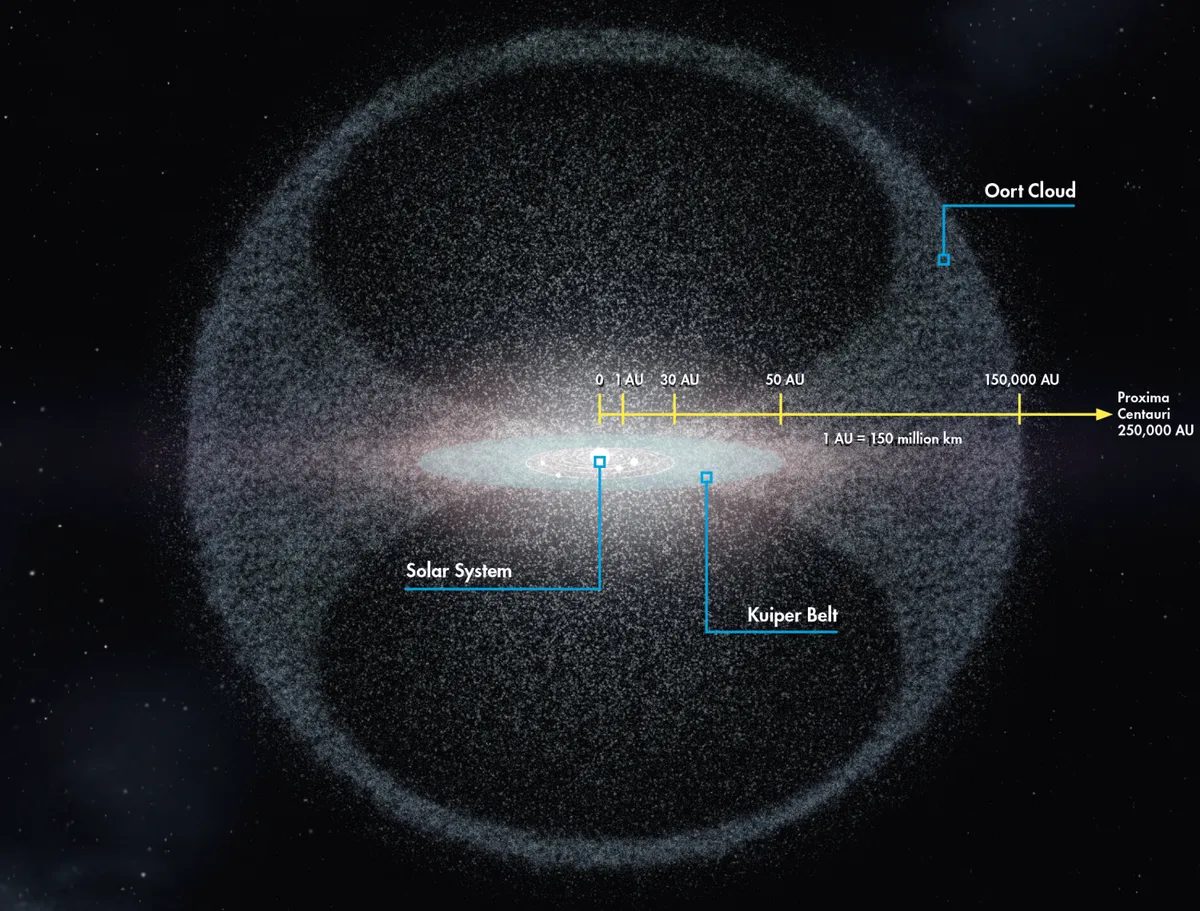

The Oort Cloud is a vast reservoir of icy bodies, numbered in their billions – perhaps trillions – that make up a ghostly shell around the entire Solar System.

Though it has never actually been observed, this spherical region is named the Oort Cloud after Jan Oort, the Dutch astronomer who suggested its existence in 1950.

More amazing space science

Oort did so to explain the appearance of comets with orbital periods of many thousands of years, reviving a similar idea that had been proposed by Estonian astronomer Ernst Öpik 18 years earlier.

Where is the Oort Cloud?

It's a tricky task, attempting to measure distance in space, but it has been suggested that the Oort Cloud begins at around a lightyear’s distance from the Sun and may stretch as far as a third of the way to the next nearest star, Proxima Centauri.

It is a region filled with frozen fragments of water, ammonia and methane left over from the formation of the Solar System.

And although the fragments are fairly insubstantial individually, together they could add up to several times the mass of the Earth.

Some of the most impressive long-period and non-periodic comets are thought to have started their journeys here, after being dislodged by some unknown event.

The Oort Cloud is thought to have sent us comets C/1996 B2 Hyakutake, C/2011 L4 PANSTARRS and C/2012 S1 ISON. But it is not the only source of them.

Short-period comets are thought to come from somewhere much closer – a region beyond Neptune called the Kuiper Belt and the area just beyond it known as the ‘scattered disc’.

Can we see the Oort Cloud?

We don’t have any observations to confirm whether the Oort Cloud exists or not, and it is too far to study with space probes.

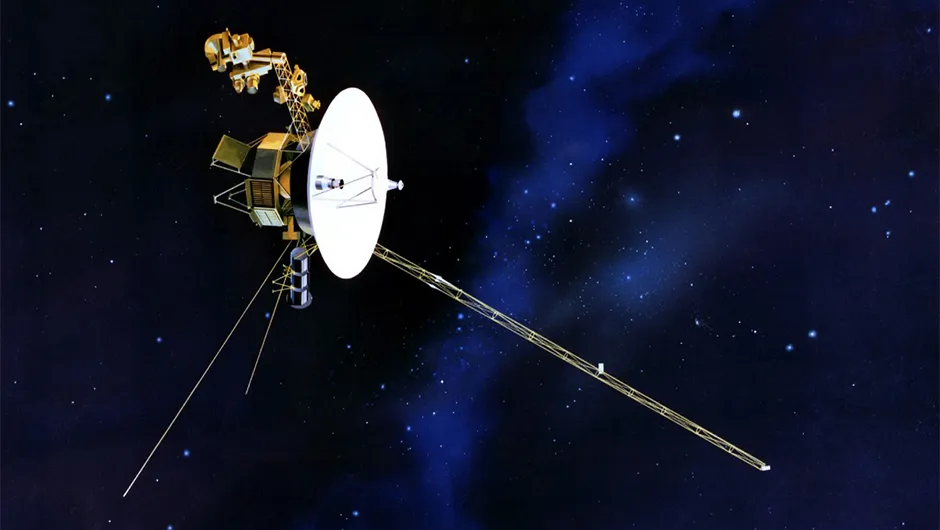

NASA's Voyager probes, which have crossed into interstellar space, will not reach it for hundreds of years, by which time they will be long past their useful life.

Even New Horizons, which has reached the Kuiper Belt, will be unable to help us.

But the theory that the cloud exists is a neat one, explaining how these icy Solar System leftovers come to grace our skies.

It came from the Oort Cloud...

What triggers the dislodging of an icy object in the Oort Cloud to send it hurtling into the inner Solar System?

Astronomers say that, in such a remote zone far from any giant planets and where even the Sun has little effect, the slightest external force can influence these bodies.

One such force could be the pull of the Milky Way, termed the galactic tide.

But a passing star or gas cloud might similarly alter the orbits of frozen chunks, sending them sunwards.

Even collisions between the objects themselves could set them on a new course towards the inner Solar System.

Some astronomers believe, however, that there could be a sizeable object within the Oort Cloud itself that is disturbing it – a hypothetical gas giant that may be several times the size of mighty Jupiter.

This potential ‘ninth planet’ even has a name, Tyche.

Its existence was proposed in 2002 to explain why one part of the Oort Cloud appears to be sending us more comets than others.

The theory remains highly controversial, but if Tyche does exist there is the chance it might be discovered in archived observations of from NASA’s WISE mission, which has imaged much of the sky to reveal cold asteroids and similar objects.

This article originally appeared in the November 2013 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.