Since their discovery in 2007, fast radio bursts (FRBs) have continued to fascinate, not least because they have avoided simple explanations.

These sudden and intense flashes of radio waves, detected by telescopes around the world, are among the greatest astronomy discoveries of recent memory.

Often they seem to be one-off events, suggesting some sort of catastrophic explosion such as an extreme supernova might be responsible.

But some fast radio bursts repeat, occasionally on a regular pattern.

There is evidence even that gravitational lensing could be causing observed repetitions of fast radio bursts.

The fact that these things are fast, lasting just milliseconds, and bright, emitting a huge amount of energy, makes most people think they’re related to compact objects such as neutron stars or black holes (colliding neutron stars seem to fit most of the observed properties of at least some bursts).

More from Chris Lintott:

- Why do some galaxies have more supernovae than others?

- The mystery of double-dipping stars

- Can we measure the mass of the Milky Way?

Other suggestions – from active galactic nuclei to misbehaving pulsars to exotic behaviour in string theory – abound in the scientific literature.

There are many cases of strange signals coming from space, like the story of radio signal ASKAP J173608.2-321635.

One of the problems is that although there’s good evidence to suggest most fast radio bursts are distant, identifying their host galaxies is hard.

There is an exciting paper that takes a close look at one burst and manages to find its home.

Tracing the source of a fast radio burst

FRB 20181030A has been detected nine times by the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME) telescope, the world’s premiere FRB-hunting instrument.

Because it has been observed so often, the burst can be traced to a much smaller region of the sky than normal – a region that contains seven known galaxies, one of which, NGC 3252, is much closer than the others.

The odds of having a system that close – just 65 million lightyears away from the Milky Way (a stroll to the shops in galactic terms) – to where the FRB occurred by chance is estimated to be around 1 in 400, making this one of the closest FRBs to have a host galaxy determined.

In fact, two other repeating bursts have been found closer than this one and combining the three allows us to estimate how common they really are.

It turns out that by doing so we can rule out some of the most popular potential culprits.

People have blamed FRBs on a form of rapidly spinning, magnetically active neutron star known as a magnetar, but there aren’t nearly enough of these to account for even the three nearby examples we see.

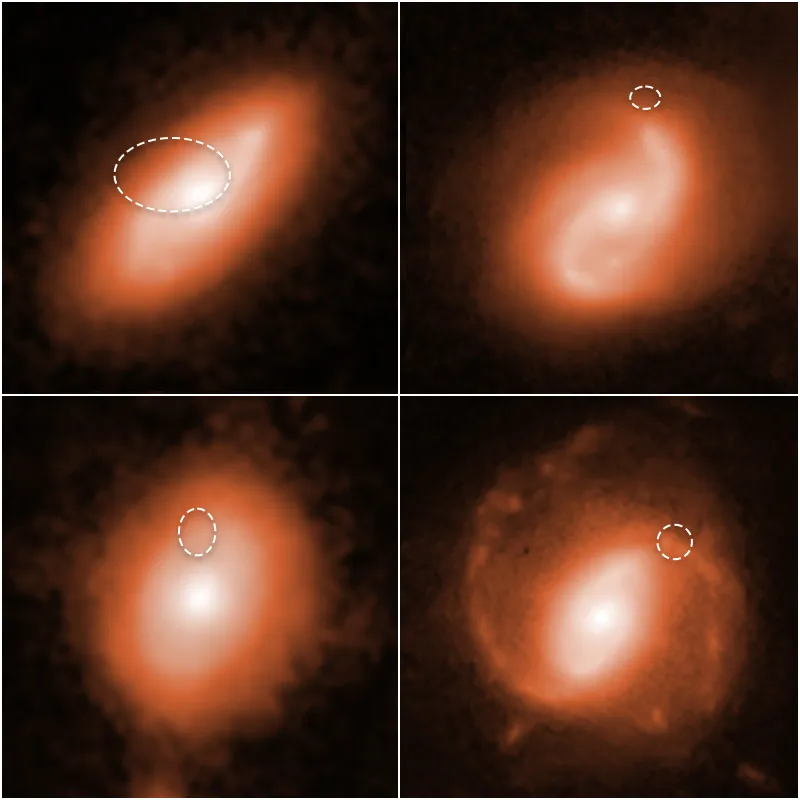

On the other hand, all of the five repeating FRBs whose host galaxies have been traced live in spiral systems.

This might be an excellent clue: spirals tend to host supernovae caused by the collapse of massive stars (except that one of the five is from a globular cluster in M81, a place where there should be no such events).

What’s more, all of the five are (relatively) low-energy events – much less spectacular than the cosmic beacons seen in the more distant Universe – so there may be more than one mechanism at work.

FRBs are a proper cosmic mystery, with astronomical detectives still very much on the trail of whatever is causing these spectacular events.

Identifying the host of this particular burst is a big step forward, but there’s a lot more still to discover.

Chris Lintott was reading A Local Universe Host for the Repeating Fast Radio Burst FRB 20181030A by M. Bhardwaj et al.Read it online at ui.adsabs.harvard.edu.

This article originally appeared in the January 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.