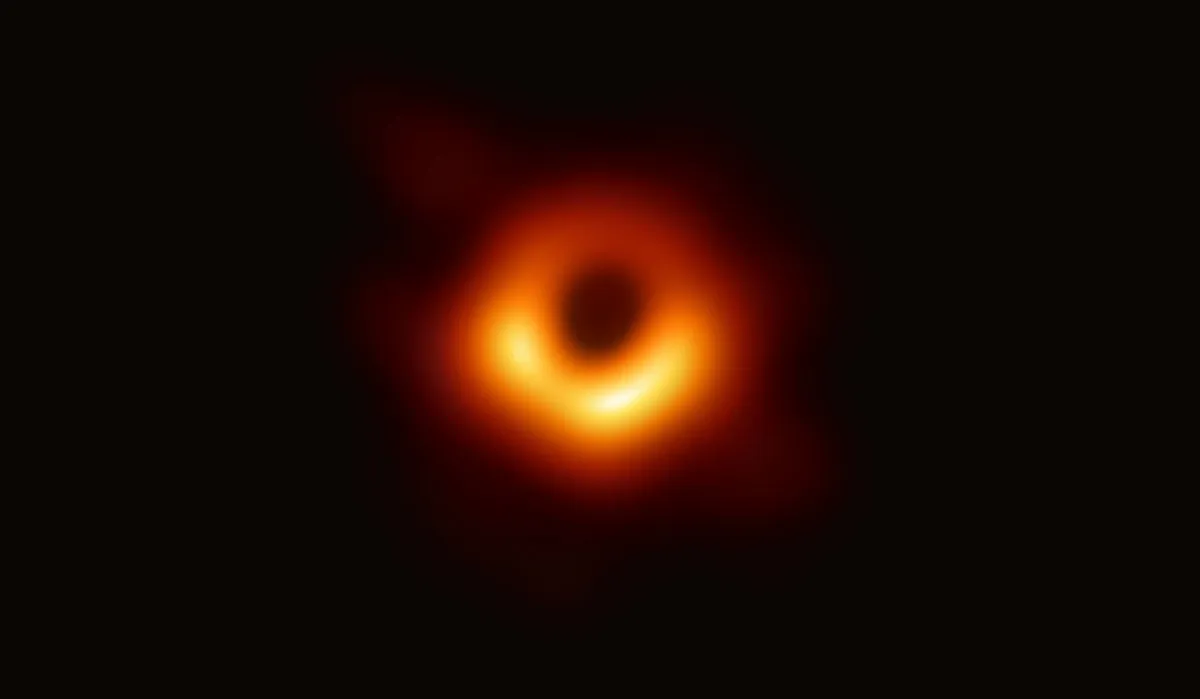

Black holes are having something of a moment. The last few years have seen the detection of gravitational waves from colliding black holes, and there was the Event Horizon Telescope’s magical image of the shadow of the large black hole that lurks at the heart of M87.

Last year saw the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics split between Roger Penrose for his theoretical study of these enigmatic objects and the two teams who have monitored the movements of stars around Sagittarius A* – our own Galaxy’s supermassive black hole.

With so much attention, it’s somewhat surprising to hear that we may not know where the closest black hole to Earth is.

The problem is that they are, well, black – a lone black hole wandering through the Galaxy would be nearly impossible to spot.

Things are easier when the black hole in question is the companion to a normal star, and the team behind a recent paper think they’ve spotted just such an object.

The star in question is V723 Monocerotis, a bright red giant 1,500 lightyears away from the Sun. It has long been catalogued as an eclipsing binary – a double star that fluctuates in brightness as the two components pass in front of each other.

New data, from NASA’s exoplanet-hunting TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) mission, the All Sky Automated Survey (ASAS) and the brilliantly named Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope (KELT), has led to a rethink.

V723 is indeed a double system but a rarer ellipsoidal variable. The red giant is being pulled out of shape by an unseen companion, and this distortion means it changes brightness as it completes its orbit.

But what is the companion? There is no obvious star contributing to either the system’s spectrum or the observed changes in brightness.

In a few recent cases, systems that astronomers thought might contain black holes turned out to be disappointments, containing normal stars so hot that they didn’t significantly contribute to the visible spectrum.

Here, we know how much ultraviolet light the system emits and so it can’t be hiding a hot, massive companion.

As a result, the second object has to be a compact object, either a black hole or a neutron star.

The behaviour of the giant suggests that the unseen companion weighs in a little under three times the mass of the Sun. This is just under the theoretical maximum mass for a neutron star, but it would make it by some distance the most massive such object known.

As a result, the authors suggest that a black hole is the most likely explanation.If that’s right, this is a record-breaking system.

It would be the closest known black hole, and the lowest mass black hole found in this sort of system.

In fact, it would be right in the middle of the so-called mass gap that sits between the lowest mass black holes known and the heaviest neutron stars.

All sorts of explanations have been proposed over the years for why such a gap should exist, but if these results from V723 bear out then it may just be that the smallest black holes have been there all along, waiting for us to find them.

Chris was reading A Unicorn in Monoceros: the 3M dark companion to the bright, nearby red giant V723 Mon is a non-interacting, mass-gap black hole candidate by T. Jayasinghe et al. Read it online at arxiv.org.

This article originally appeared in the March 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.