The phases of the Moon are something you've noticed from time to time in the night sky, but perhaps never really thought about.

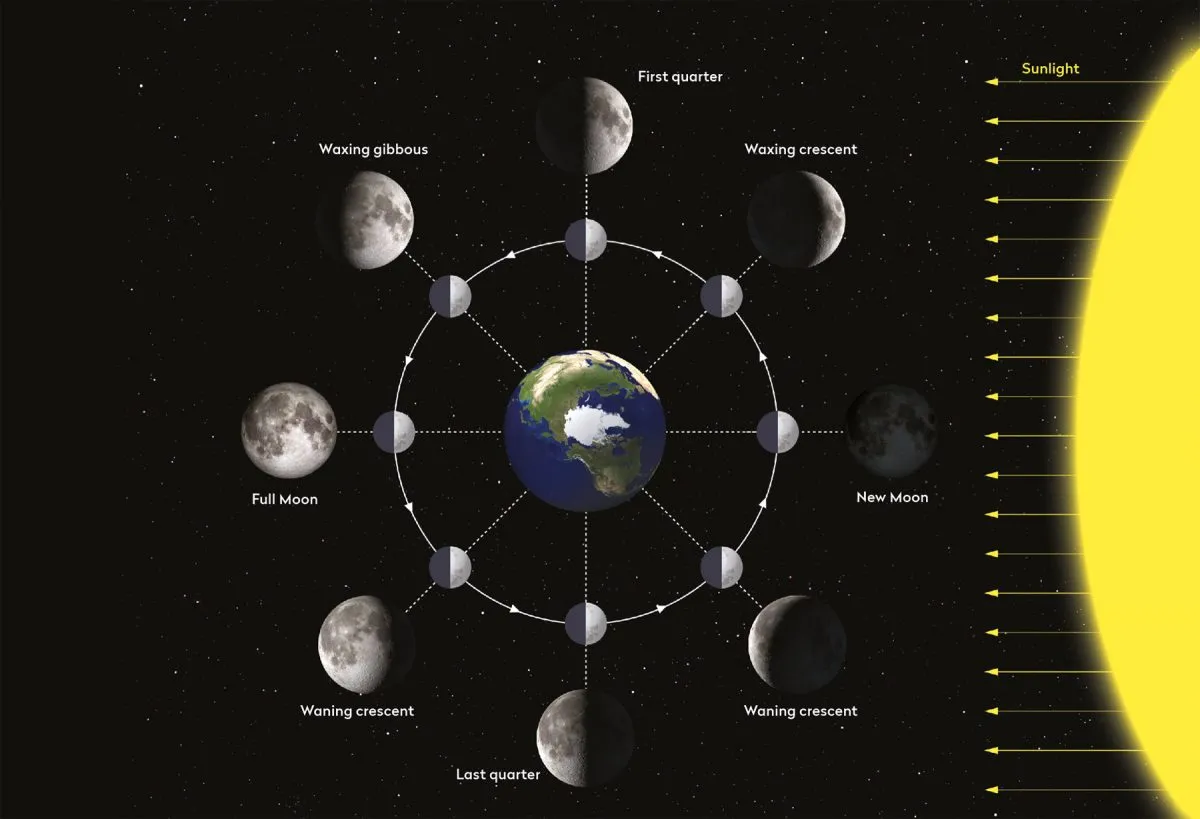

What causes the phases of the Moon is really nothing more than the Moon's orbit around Earth, Earth's orbit around the Sun, and how this all appears from our pespective.

The Moon may appear to change shape, but the bright surface you see and the 'moonlight' that reaches Earth is sunlight reflecting off the lunar surface.

As the Moon orbits our planet, its varying position means the Sun lights up different regions, creating the illusion that the Moon is changing shape over time.

Keep up with the phases of the Moon by signing up to receive the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter every week and downloading our 2024 lunar phases poster (PDF).

Observing the phases of the Moon

The best way of getting to know the phases of the Moon is to go out on a clear night when the Moon is in the sky and observe it.

For more on this, read our guide on how to observe the Moon.

The Moon lies on average 384,400km from Earth, it’s stunning to the naked eye and through binoculars or a small telescope.

It's also a great target to photograph. Read our guide on how to photograph the Moon or our beginners' guide to astrophotography.

The Moon's journey around Earth

The Moon seems serene but it is hurtling eastward travelling at 3,682 km/h.

Since its almost circular orbit is tipped just 5° relative to Earth’s, it more or less follows the ecliptic (the Sun’s apparent path) across the sky.

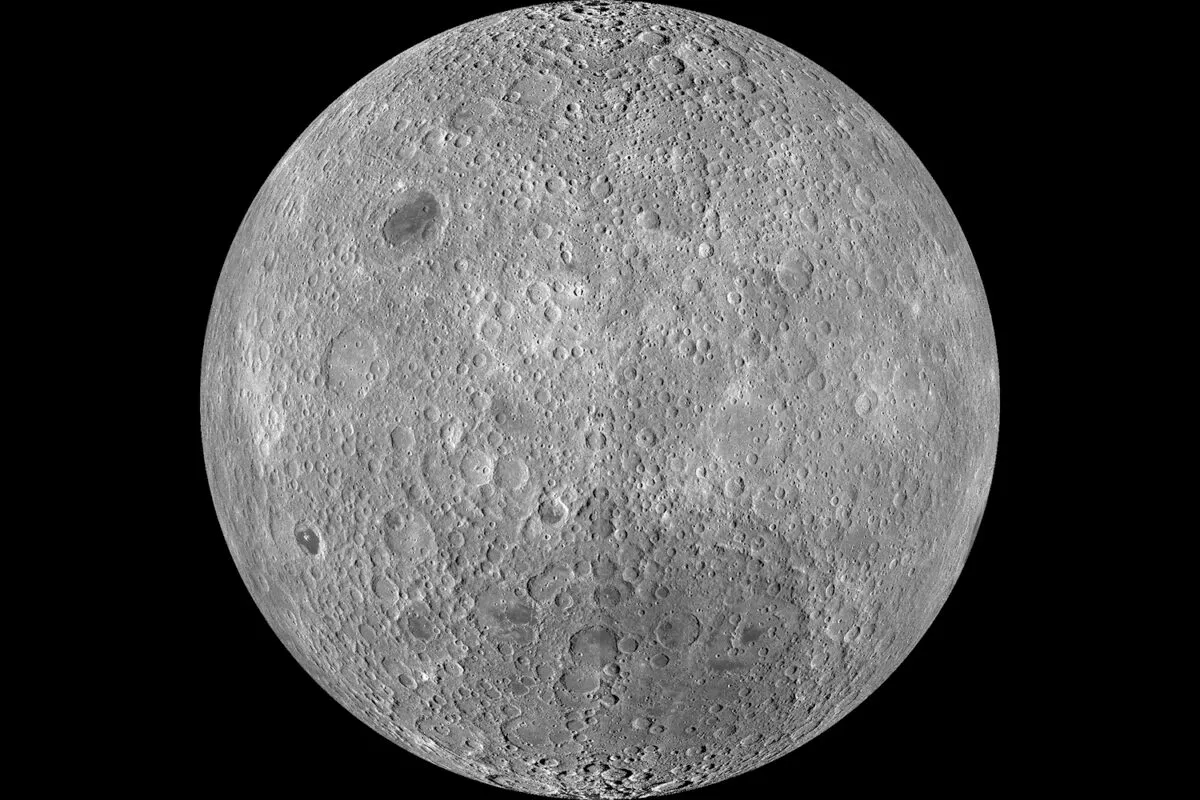

You may have noticed that the Moon always keeps the same face turned towards us.

This is because it rotates once on its axis in exactly the same time it takes to orbit Earth – 27 days and seven hours.

This synchronisation is called tidal locking and is a result of Earth’s gravitational effect on the young Moon when it was forming.

As a result, we don't see the far side of the Moon. But we also don't only see 50% of the Moon, either.

We get to peak 'round the corner' a bit every now and then during a phenomenon known as lunar libration.

During its elliptical orbit around Earth, the Moon moves through ‘phases’.

This is the term we use to describe how much of the lunar disc appears illuminated as seen from Earth.

This elliptical orbit, combined with the phases is also what leads to the appearance of a so-called supermoon.

In fact, the Moon is always half lit, we just don’t see it that way. Which ever of the Moon phases we’re seeing, the opposite phase is happening on the far side of the Moon.

And while we only ever see one terminator (the name given to the dividing line between the light and dark parts of the lunar surface) sweeping right to left across the lunar disc at any time, there are actually two of them circumnavigating the Moon exactly 180° apart.

There's the morning terminator (ushering in the lunar day) and the evening terminator (bringing the night behind it).

So sorry, Pink Floyd, there is no permanently dark side of the Moon.

Phases of the Moon at a glance

When describing the phases of the Moon, 'waxing' refers to the journey from new Moon to full Moon, as the Moon appears to gain more of its sunlight section every night.

'Waning' refers to the period from full Moon back to new Moon, as the Moon appears to lose more of its sunlit section every night.

The phases of the Moon are as follows:

- New Moon

- Waxing crescent

- First quarter

- Waxing gibbous

- Full Moon

- Waning gibbous

- Last quarter

- Waning crescent

Test out your knowledge of the Moon phases by playing the Half Moon Google Doodle.

Phases of the Moon explained

What many people don’t realise (even though it’s completely logical), is that there’s also a relationship between the Moon’s phases and moonrise times.

New Moon

During new Moon, we can't see the Moon.

With the Sun and Moon on the same side of Earth, they rise together but we cannot see the Moon as it’s hidden in the Sun’s glare.

There’s not much to see anyway, as its face towards us is totally in shadow.

Waxing crescent

Continuing its journey, the Moon’s western (right) edge becomes sunlit to create a sliver-thin waxing crescent.

The morning terminator starts its creep of 15.5km/h from west to east.

First quarter

The quarter Moon can confuse non-astronomers, because it clearly looks like half a Moon.

That’s because the terminator has completed a quarter (90°) of its 360° journey around the Moon.

By this logic a full Moon should be called a half Moon, but that’s just silly, right?

In this phase, the Moon rises at noon and sets at midnight.

Along the terminator, low-angled sunlight creates long shadows, throwing nearby crater and mountains into sharp relief – perfect for lunar observations.

Waxing gibbous

In waxing gibbous phase the Moon is almost fully illuminated.

The daylight area appears egg-shaped (gibbous) and is increasing in size (waxing) daily.

Full Moon

Halfway through the morning terminator’s journey, the Moon is on the opposite side of Earth from the Sun, with its near side fully illuminated and dazzling.

This is a full Moon.

Shadow-less, bleached and flat-looking, it’s not great for observation.

That’s a shame because in this phase it rises as the Sun sets, sets as the Sun rises and is visible all night long!

However, there are features you can observe during a full Moon. Why not have a look during the next full Moon?

And if it's been raining (or you happen to be near a waterfall at night!) you might be able to see a moonbow.

Waning gibbous

During the waning gibbous phase, the Moon’s western edge is consumed by darkness as the evening terminator comes into view.

The sunlit, egg-shaped area is diminishing (waning).

Last quarter

It’s seven days and nine hours since full Moon and, now 90° west of the Sun, just the Moon’s eastern (left) half is illuminated.

At last quarter phase, the Moon rises at midnight and sets at noon and, like the first quarter phase, offers staggering views.

Waning crescent

With just the eastern edge sunlit, during the waning crescent phase of the Moon you’ll admire a beautiful ‘C-shaped’ crescent.

Diminishing daily (waning) it will soon disappear as the lunar cycle concludes and the Moon returns to ‘new’.

While the Moon may keep the same face turned to us, it remains a daily changing delight to observe.

Lunar libration

Over the course of a lunar cycle, the Moon simultaneously wobbles both latitudinally and longitudinally.

These oscillations are known as librations.

Libration in latitude – nodding – occurs because the Moon’s axis is slightly inclined relative to Earth’s, enabling us to peer just a little over its north and, later in the month, south poles.

Libration of longitude – shaking – occurs because the Moon travels fastest when closest to Earth and slowest when farthest away.

Daily (diurnal) libration occurs because of our planet’s rotation.

We see the Moon from slightly different perspectives when it rises and when it sets, and this difference in perspective manifests as a slight apparent rotation in the satellite, first to the west and then to the east.

The combined effect of all the above means that instead of seeing just 50% of the Moon, over time we actually get to see about 59%.

So the phases of the Moon isn't the only way that our view of our lunar companion changes over time.