Got a pen handy? Good… grab it. And if you haven’t, grab a tennis ball, a hairbrush or any other small, non-breakable object.

Hold the object out in front of you, and let it go.

What happens? The pen/hairbrush/ball/whatever falls to the ground, of course.

That’s due to gravity.

More on gravity

Gravity is the reason pens fall to Earth, the reason we all don’t go flying off into space as Earth rotates… and the reason planets orbit the Sun.

What’s more, you’ve probably known that for roughly as long as you’ve known your times tables, and just a little less time than you’ve been able to tie your own shoelaces.

But hang on a second.

If gravity from the Sun is pulling planets towards it (which it is), then why aren’t the Solar System’s eight planets drawn inexorably towards the Sun, just as your pen/hairbush/ball is drawn inexorably towards the Earth?

After all, it’s not like there’s much in-between the Sun and those planets to stop them.

So why do planets orbit the Sun and not simply get sucked into it?

That’s because gravity is only one of the forces we have to consider when we talk about the motion of the planets.

The other is inertia. So let’s look at those forces in a little more detail.

Gravity versus inertia

Without getting bogged down in equations, gravity is an attractive force that exists between any two given objects in the Universe, and derives from the relationship between their respective sizes and masses (or densities, if you prefer).

It’s just that, most of the time, we don’t notice that force is even there, because while gravity is one of the Universe’s fundamental forces, it’s actually quite a weak one.

For proof of that contention, drop a paperclip on the kitchen floor, then use a fridge magnet to pick it up.

Congratulations, you’ve just defeated the gravitational pull of the entire planet Earth, using a teeny, tiny fridge magnet. Electromagnetism 1, gravity 0!

This means that, as gravity attempts to shape the Universe, it’s often having to do battle with other forces, and in the case of the motion of the planets, one of those forces is inertia.

Inertia? Let's turn to Isaac Newton, whose first law says every object remains at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless there's another external force acting upon it.

This resistance to a change of state of motion (or lack of motion), is inertia.

The planets, of course, ARE in motion. They have been ever since they formed because, in the near-vacuum of space, there’s no substantial force causing their velocity to change.

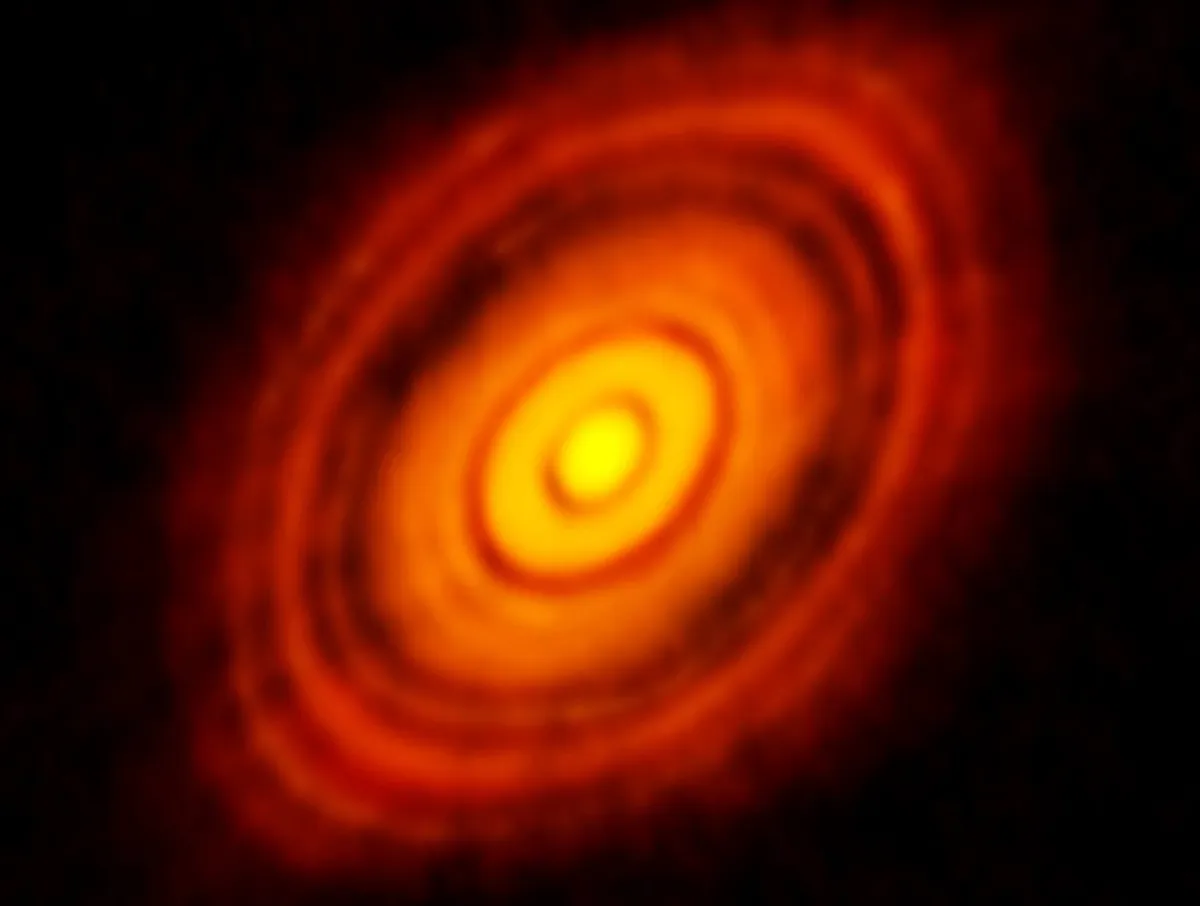

And they were already in motion WHEN they formed, because they formed out of a rapidly spinning mass of material (the Sun’s protoplanetary disc) that was already orbiting (i.e. in motion around) a much more massive body (the then new-born Sun).

So on the one hand, you’ve got eight planets, all whizzing through space at high velocities and, in the absence of any force to stop them, hell-bent on continuing to travel in a straight line forever.

And on the other hand, you’ve got the Sun with its immense gravity, endlessly trying to drag those planets toward it.

Were the planets not whizzing through space at mind-blowing velocities, if they were chugging along at 32km/h (20mph) rather than, say, 107,000 km/h (67,000mph) – the speed at which Earth travels along its orbit – then they would indeed be drawn towards the Sun, because the amount of inertia an object in motion has depends on the speed at which it is travelling.

But because the planets do move at such high speeds, inertia wins out.

The planets can’t travel in a straight line, because gravity’s pulling them towards the Sun, but neither can they fall into the Sun and perish, because inertia’s keeping them moving.

The result is that the planets begin to travel a curved path that’s effectively a compromise between the Sun’s gravity and their own inertia – and we call that equilibrium state an orbit.

Astronomers sometimes put it like this: the planets ARE constantly falling towards the Sun. It’s just that they’re constantly missing.

Satellites, gravity and inertia

Another way of looking at all this, is to reverse the process and think about humans trying to put satellites into orbit around the Earth.

The key is to launch the satellite at a sufficiently high velocity that it will overcome Earth’s gravity, staying up in the air and not falling back down to Earth.

But not at such a high velocity that the satellite will escape Earth’s gravity entirely and zoom off into space.

In the case of satellites, we want them to orbit at a certain altitude and we know their mass, so we can engineer a velocity that will allow that to happen.

Think of the International Space Station. It's not that astronauts are floating because they're in space, where there's no gravity.

They're floating because there IS gravity. They – and the Space Station – are constantly falling towards Earth, and constantly missing it.

The effect is similar to someone 'floating' in an ever-falling elevator.

Watch a timelapse of Earth from the Space Station and it seems like the ISS is passing over Earth like a plane in flight.

But another way of looking at it is that the Space Station is falling towards Earth, and constantly missing.

With the planets, of course, mass and velocity were a given from the start – which determined the amount of inertia they had when they formed.

And how much inertia they could muster up determined the distance from the Sun at which they could reach the equilibrium state described above – the size of their respective orbits, in other words.

So the interplay between gravity and inertia isn’t just what keeps the planets spinning around the Sun – it’s the reason they’re where they are in the first place!

Gravity caused the planets to form; gravity causes them to orbit the Sun.

Yet most planets don't seem to orbit their host stars in a perfect circle: they have eccentric orbits, meaning the orbits are slightly egg-shaped.

Read about exoplanet TIC 241249530 b for an example of a really eccentric orbit!

A perfect Solar System?

But what are the chances that all of the planets of the Solar System happened to gain just the right balance between gravity and inertia to keep them in orbit around the Sun?

If you think about it, it's likely that some young planets – or protoplanets – forming around the young Sun DIDN'T have the right orbital balance, and didn't survive.

They may have been flung out into space or fallen into the Sun, never getting the chance to fully form.

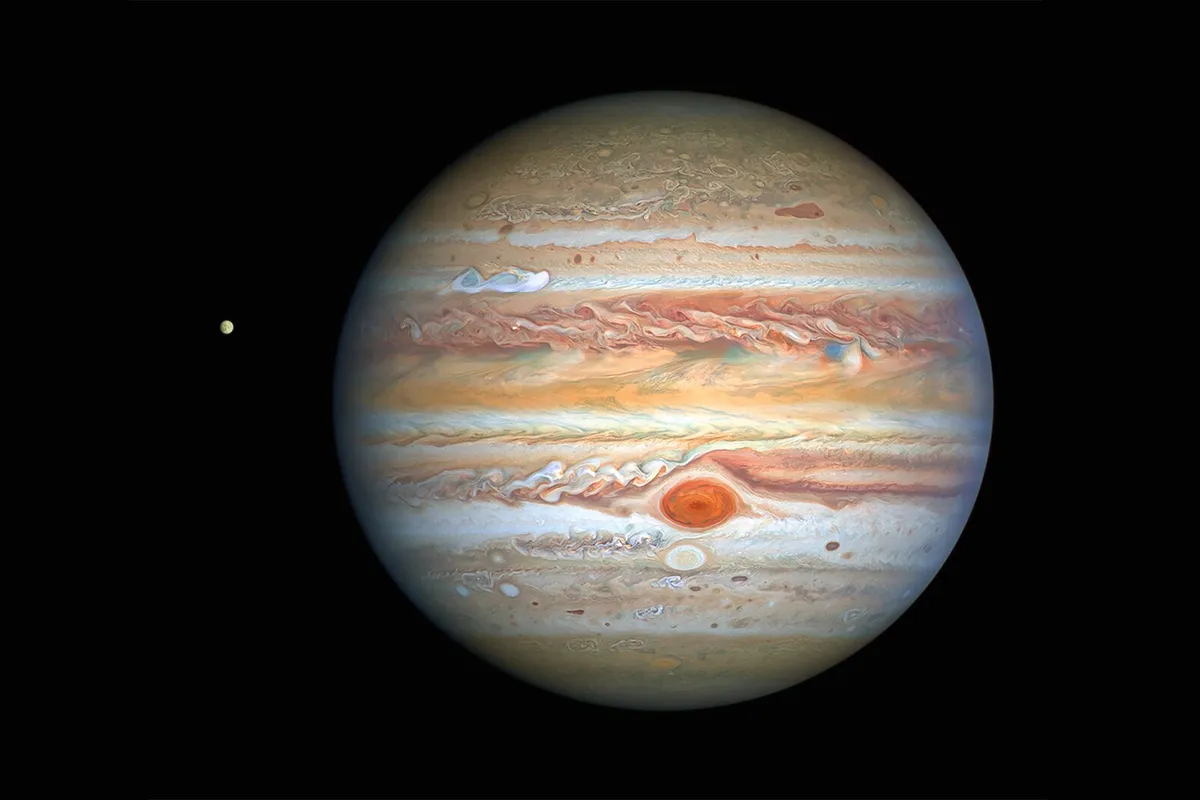

There's even a theory called the Grand Tack that says a young Jupiter, now the biggest planet in the Solar System and fifth in distance from the Sun, long ago moved inwards towards the Sun, getting as close as Mars is today.

It then moved outwards again, wreaking gravitational havoc as it did so.

The eight planets of the Solar System we know and love have such nice, balanced orbits today because those are the ones that that early. chaotic era.

After all, the Solar System has had about 4.5 billion years to settle into a relatively stable state of being.

Should nothing happen to change that – a huge star wandering too close to our Solar System or a large impact drastically changing one of the planets' orbits, for example – the Solar System is likely to stay that way (until the Sun begins to reach the end of its life, of course).

There are a few notable minor exceptions, like for example the fact that the Moon is slowly moving away from Earth in its orbit, at a rate of about 3.8cm a year.

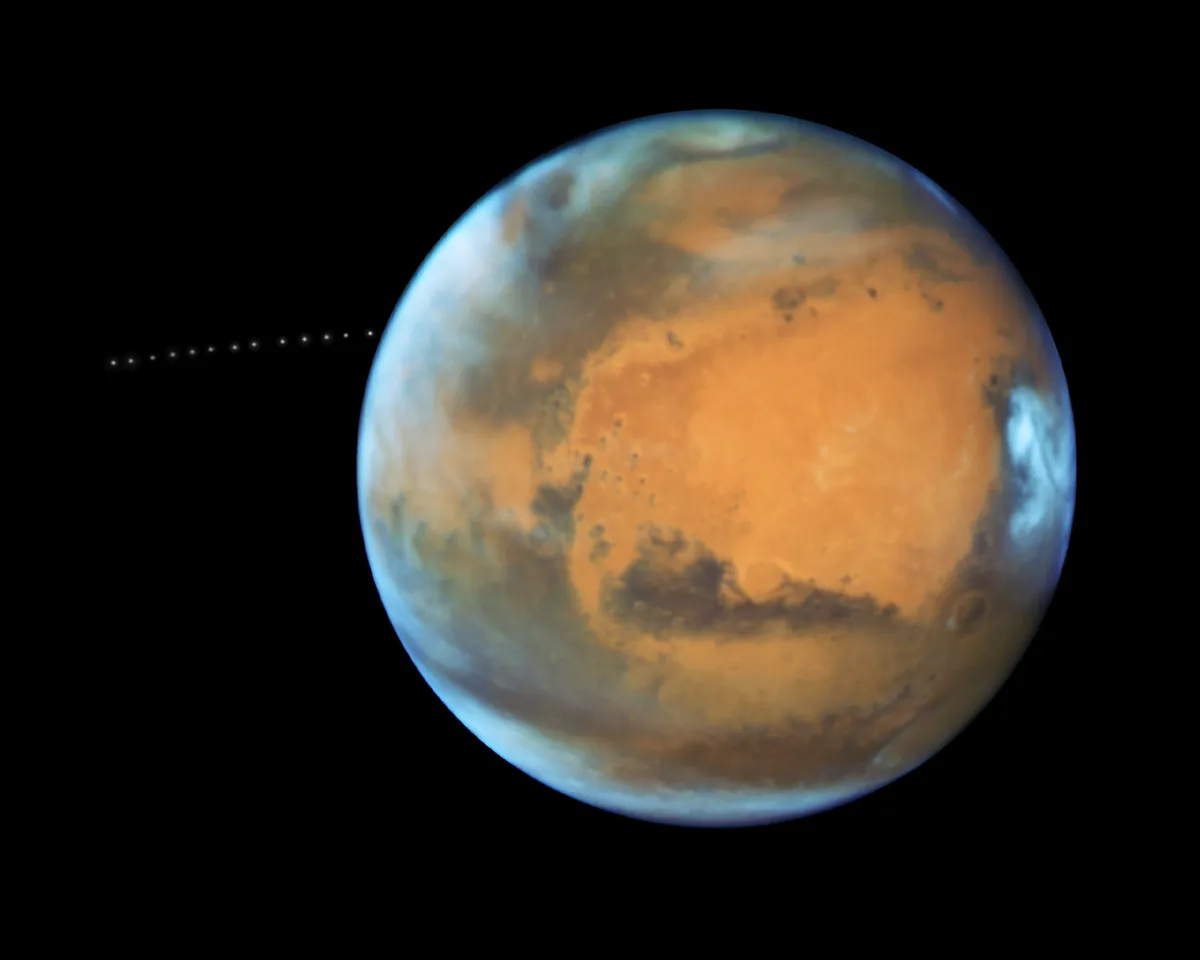

And the orbit of Mars's moon Phobos, on the other hand, is 'decaying', taking it closer to Mars at a rate of 1.8 metres every 100 years, says NASA.

This means that, within 30 to 50 million years, it could disintegrate and form a ring around Mars, or impact the Red Planet and be destroyed entirely.

A good example of how not every orbit is perfect, and how even something as apparently unchanging as our ever-reliable Moon is subject to the laws of physics.