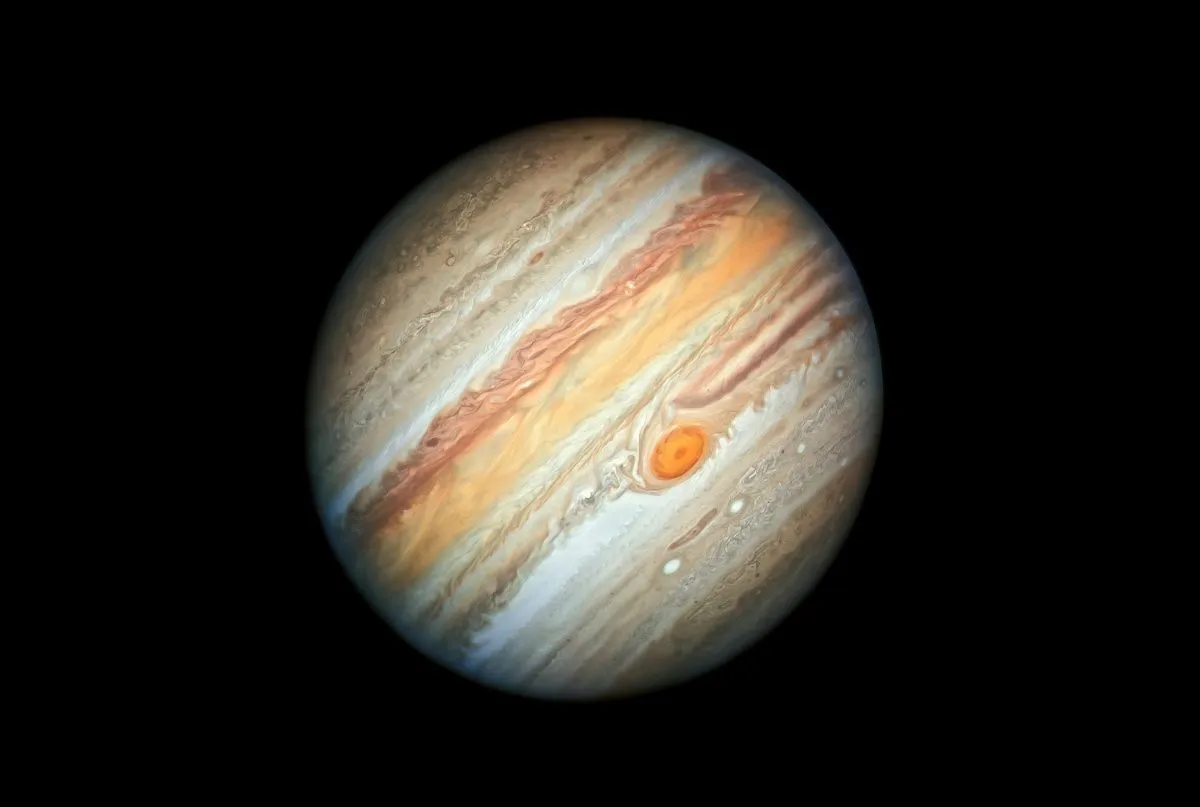

Jupiter is the undisputed King of the Planets. It’s a gas giant, its huge mass made up of hydrogen and helium gas.

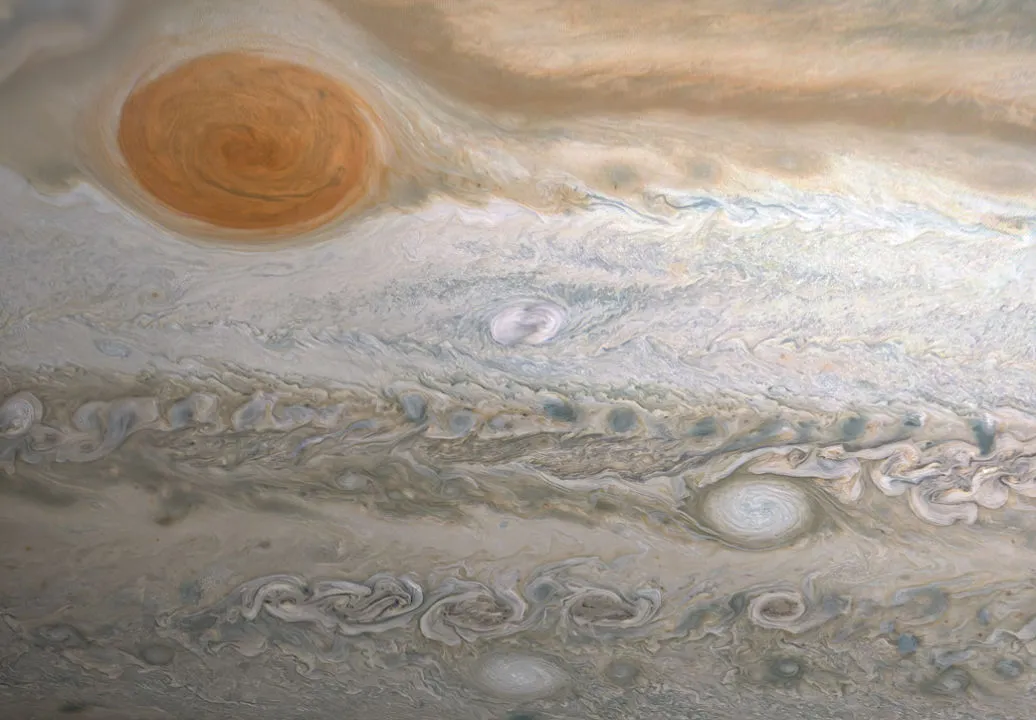

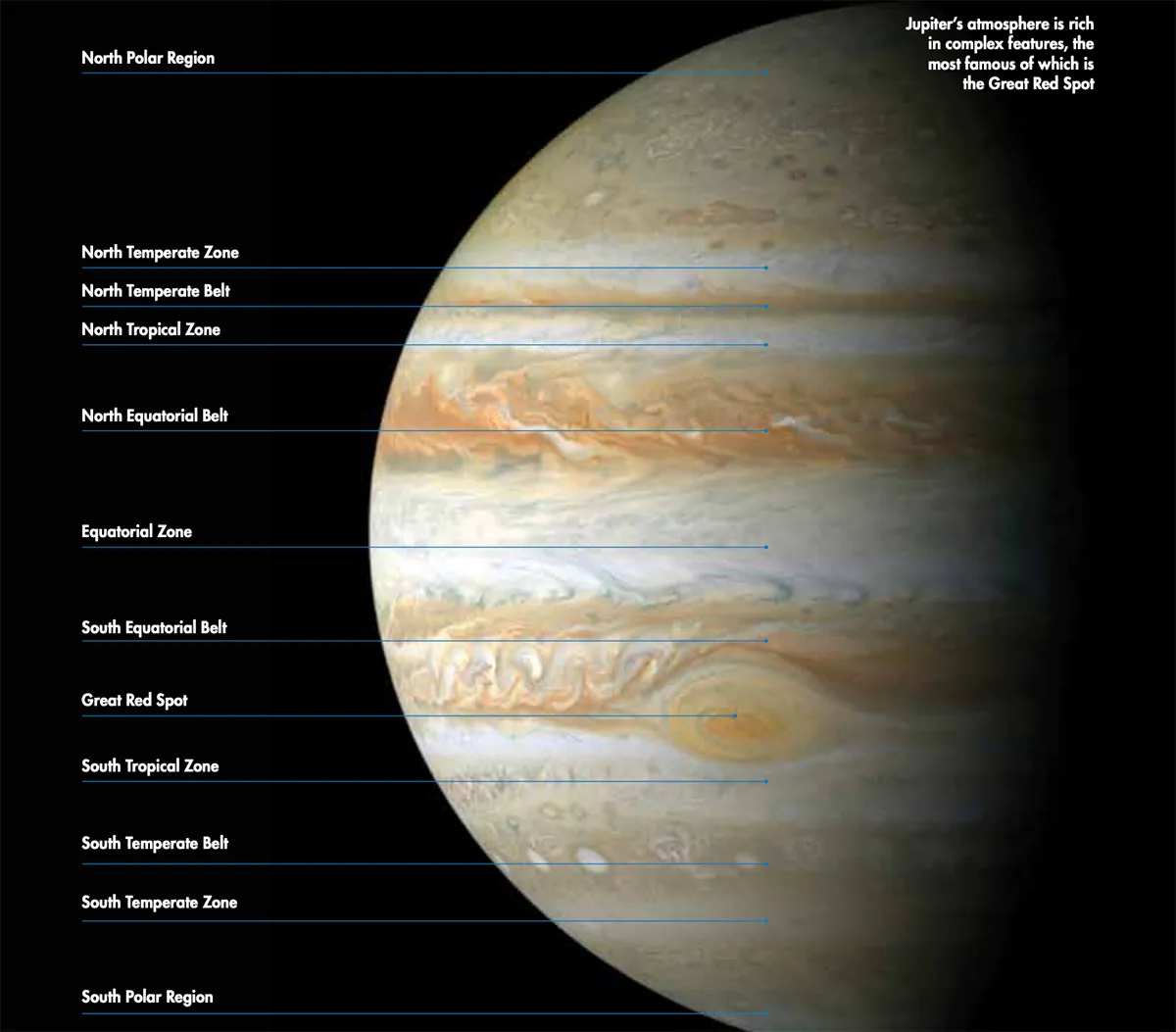

Jupiter's upper atmosphere is streaked by dark belts and white zones – streams of clouds that blow in alternating directions around the planet.

Caught between these are several huge storms. The largest of these, the Great Red Spot, has been raging for at least 150 years and could easily swallow the entire Earth.

Yet these features only make up the top few hundred kilometres of Jupiter’s atmosphere.

It’s thought that some kind of solid core lies at Jupiter’s heart, as the density of the planet would be incredibly intense, but no one is sure exactly what this core would look like or what it’s made of.

Jupiter's huge mass influences the entire Solar System, particularly the asteroid belt where the constant tug of the planet has created openings in the belt known as the Kirkwood gaps.

Here is our rundown of the greatest facts about Jupiter.

Quick facts about Jupiter

- Diameter: 142,984km at equator (11.2 times Earth), 133,708km through poles (10.5 times Earth)

- Mass: 1898 trillion trillion kg (318 times Earth)

- Distance from the Sun: 778.6 million km (5.27 AU)

- Length of day: 9.9 hours

- Length of year: 11.9 years

- Number of moons: 95

- Average temperature: -110ºC

- Type of planet: Gas giant

It’s a big unit

Here’s a fun fact for you: if you put Earth and the other six Solar System planets together, they still wouldn’t have even half the mass that Jupiter has!

With a radius of 69,911km (42,440mi) it’s 11 times wider than Earth, and if you could hollow it out, you could fit over 1,000 Earths inside it.

It’s made of gas

Our Solar System is home to several types of planets. Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars are all essentially big lumps of rock.

But Jupiter and Saturn are composed primarily of gas (largely helium and hydrogen), while Uranus and Neptune are basically made of various ices – primarily frozen water, ammonia and methane.

It’s named after the Roman king of the gods

It’s the largest of the Solar System planets, so why wouldn’t it be? The genitive form of Iuppiter, Iovis, gives us the English adjectival form ‘Jovian’ – but as the Greeks called both the same god and the planet Zeus, you’ll sometimes also see Jupiter-related terms that start with the Greek-derived prefix ‘zeno’.

Zenographic coordinates, for instance, are grid references (like latitude and longitude on Earth) that denote a specific point on the planet’s surface.

Its best-known feature is a monstrous storm

Along with lunar craters, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot has to be one of the most widely recognised features to be found anywhere in the Solar System.

But it’s not a topological feature: instead, it’s a huge cyclone that measures over 16,000km (10,000mi) across – roughly 1.3 times the diameter of Earth – and that’s been raging constantly since at least the 1830s, and possibly since as long ago as 1665.

It has the shortest day in the Solar System

Despite its gargantuan proportions, Jupiter is spinning very quickly on its axis: it takes just 10.5 hours for the gas giant to make a full rotation.

It’s a tad more sluggish when it comes to orbiting the Sun, though. One Jovian year equates to a little under 12 years (4,333 Earth days, to be precise).

Jupiter has rings

And no, we’re not thinking of Saturn here… Jupiter really does have rings! They’re just small, dark and faint. So small, dark and faint, in fact, that we didn’t know they were there at all until Voyager 1 made an historic fly-by in 1979.

But they’re there, and they’re thought to consist of dust ejected when meteoroids crash into the planet’s inner moons.

Jupiter has lots of moons

As with rings, Saturn has the edge here, boasting a whopping 274 confirmed moons (128 of which were only recently discovered). But Jupiter’s no slouch in the satellite department either, with 95 moons officially recognised by the International Astronomy Union (IAU).

Factor in ‘small body moons’ – irregular rocky or metallic objects with very large orbits, much like asteroids and comets – and that number soars even higher.

It has no surface

As Jupiter is mostly made of gas, it has no solid surface that you could ever land a spacecraft on. But you can’t fly through it like a cloud, either. The pressures and temperatures deep inside the planet would crush, melt and/or vaporise any spaceship that dared to venture too far inwards in seconds.

Jupiter has the Solar System’s biggest ocean

While Jupiter is, as we’ve seen, mostly made of helium and hydrogen, the immense pressures found inside the planet force these gases into their liquid form, creating a vast internal ocean of liquid hydrogen.

Therefore, arguably Jupiter has the biggest ocean in the Solar System.

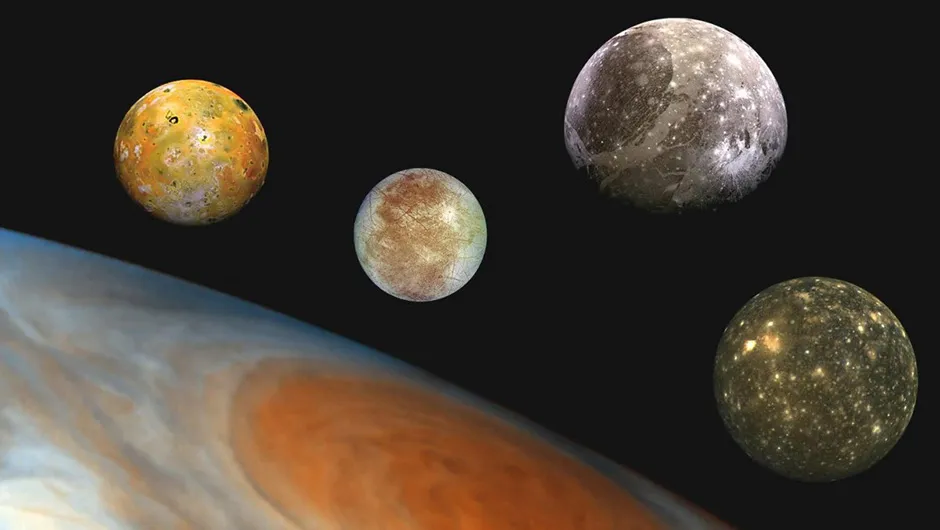

Its four largest moons were discovered by Galileo

Pretty much the first thing Galileo Galilei did, after coming up with the first truly practical telescope in 1609, was point it at Jupiter and discover its four largest satellites.

Accordingly, Io, Europe, Ganymede and Callisto are known to this day as the Galilean moons – even though it was Galileo’s contemporary Simon Marius who named them.

Its moons helped prove heliocentrism

In the early 17th Century, the jury was still out as to whether the Earth orbits around the Sun (heliocentrism) or vice versa (geocentrism). Galileo’s discovery of bodies orbiting Jupiter proved that the entire cosmos didn’t, in fact, revolve around the little blue marble that we live on.

alileo’s championing of a heliocentric world view got him into trouble with the Catholic Church. He was tried for heresy and spent the last 10 years of his life under house arrest. But this discovery, along with Johannes Kepler publishing his three laws of planetary motion a few years later, would prove to be one of the most important nails in geocentrism’s coffin.

Jupiter's largest moon is bigger than Mercury

Ganymede has a diameter of 5,262km (3,270mi) while Mercury has a diameter of just 4,880km (3,032mi).

Composed of rock and water in roughly equal proportions, Ganymede has a vast subsurface ocean sandwiched between two layers of ice, the inner of which wraps around a rocky core.

It has a stripy appearance

The bands that we see on the planet’s 'surface' – which, as we now know, it doesn’t actually have! – are gases in its atmosphere. Jupiter’s atmosphere is thought to consist of three layers, with the outer layer made of ammonia ice, the middle layer likely made of ammonium hydrosulphide crystals, and the inner layer believed to be composed mostly of water ice and vapour.

Plumes of gases containing sulphur and phosphorus rise from the planet and the planet’s rapid rotation causes these plumes to stretch out into the bands of cloud that give the planet its stripy appearance. These are known as Jupiter's belts and zones.

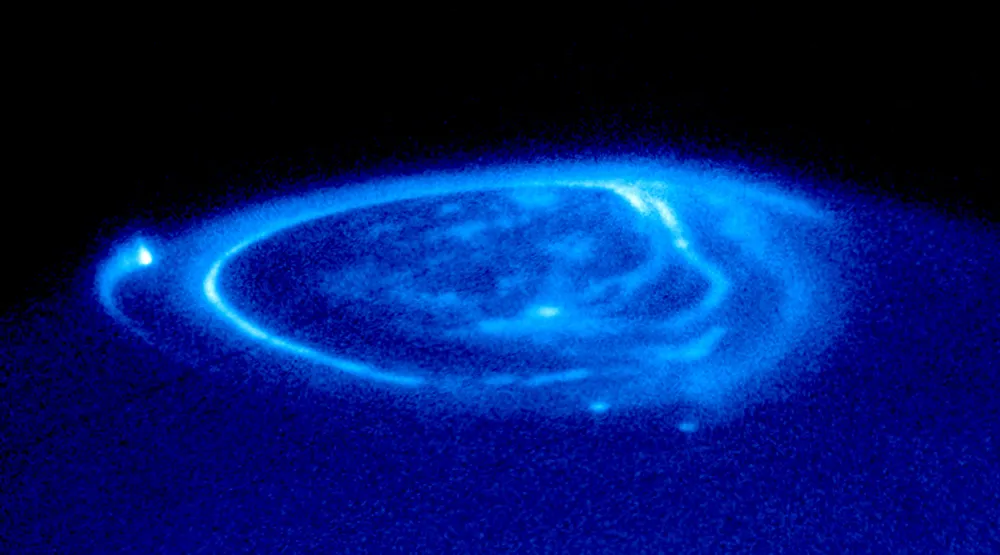

It has a large, powerful magnetosphere

Jupiter’s magnetosphere – the area surrounding a planet or other large body within which charged particles come under the influence of the planet’s magnetic field – is huge. It stretches out up to three million kilometres (two million miles) towards the Sun and up to one billion kilometres (600 million miles) towards Saturn on the opposite side, and is up to 54 times more powerful than Earth’s.

The magnetosphere rotates with the planet and sweeps up any charged particles it encounters. It then draws these particles closer and accelerates them to extremely high energies – with the result that Jupiter is surrounded by bands of lethal radiation.

Jupiter's aurorae put the Northern Lights to shame

Because Jupiter has the large, powerful magnetosphere described above, there’s a heck of a lot of electrical energy knocking around in the upper layers of its atmosphere.

Unsurprisingly, when the solar wind crashes into this highly-charged environment, sparks fly – making Jupiter's aurorae some of the most spectacular found anywhere in the Solar System.

It’s the oldest planet in the Solar System (probably)

The only sure way to tell a planet or other body’s age is by radiometric dating of rock samples – and we don’t have any samples of Jovian rock, for reasons that should be fairly obvious by now.

But Jupiter and Saturn are believed to have been the first Solar System planets to form, followed by the ice giants, and then the rocky planets last. If that’s correct, then that would make Jupiter 4.6 billion years old, compared to Earth’s 4.4 billion years.

It can be seen with the naked eye

Though you’ll need a decent telescope to make out Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, banded atmosphere or Galilean moons, you can actually see Jupiter with the naked eye.

Though you could easily be forgiven for thinking it was a very bright star, because…

Jupiter is the third-brightest object in the night sky

Only the Moon and Venus shine brighter. None of these three objects emits light themselves, of course. The light we see is merely sunlight reflected off their surfaces. But in the case of Jupiter, that’s one massive surface, which means lots of reflected light.

The Moon and Venus are a lot closer, though, so while they don’t reflect as much light, due to their smaller surface area, they appear brighter from where we’re standing.

It shares its orbit with over 10,000 asteroids

Jupiter’s path around the Sun is also the orbit of over 10,000 asteroids. The first of these was identified by German astronomer Max Wolf in 1906, and collectively they’re known as Trojan asteroids.

These asteroids clump together at two points, and somewhat confusingly, those that orbit the Sun on Jupiter’s orbit but 60° ahead of it are known as the Greek camp, while those that orbit the Sun 60° behind Jupiter are known as the Trojan camp. But they’re all Trojans, whether they’re in the Trojan or the Greek camp. The largest Trojan, 624 Hektor, has a diameter of around 225km (140mi).

Its moon Callisto is the most heavily cratered in the Solar System

Callisto has a mass of 1.08 x 1023 kg, and a diameter of 4,820km (2,995mi). Almost as large as Mercury, it is the third-largest Solar System moon overall (after Ganymede and Saturn’s moon Titan), and its entire surface is heavily cratered.

With no plate tectonics or volcanism at play, impacts by other celestial bodies soon after Callisto’s formation have been the dominant influence in shaping its evolution.

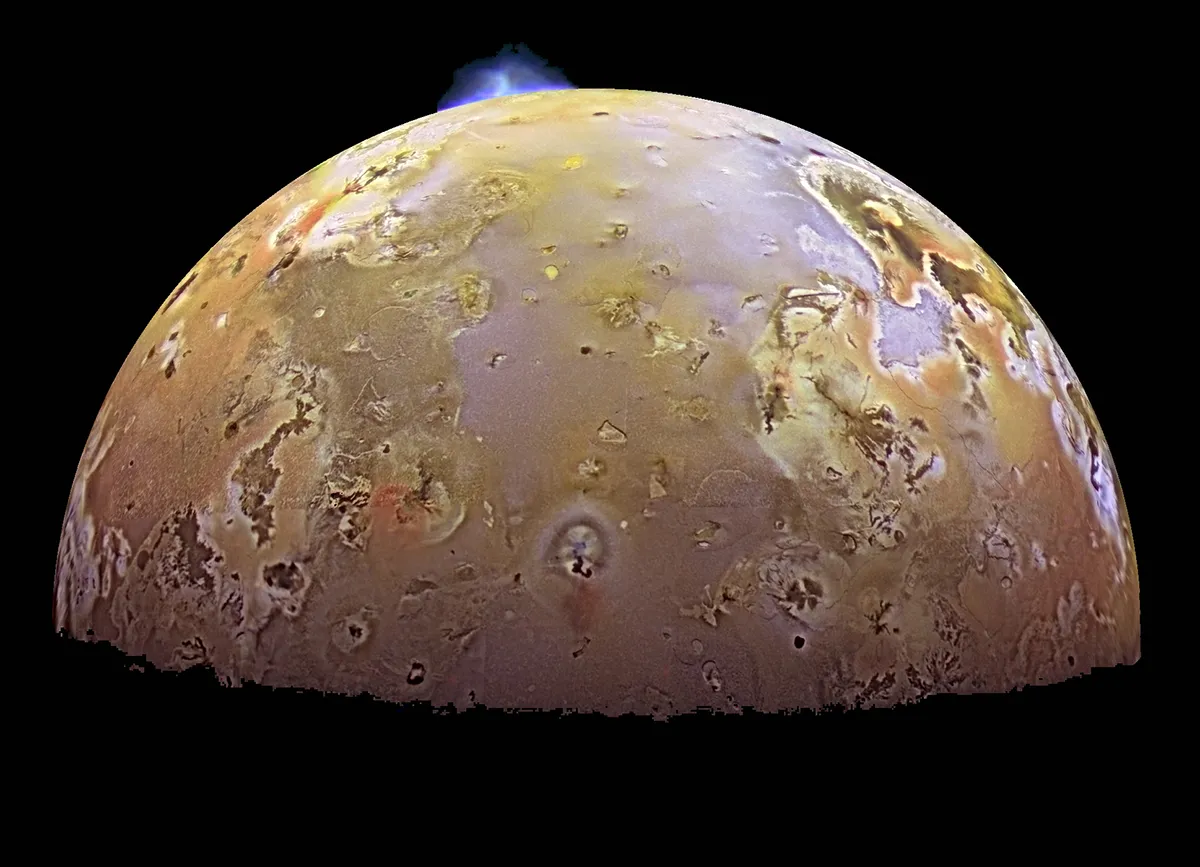

Its moon Io is a hotbed of volcanic activity

In complete contrast to its larger sibling Callisto, Io – which, with a diameter of some 3,463km (2,151mi), is just slightly larger than our own Moon – is one of the most geologically active places in the Solar System, with over 400 active volcanoes.

Outflows from these can cause Io to assume different hues when seen through a telescope – it can appear yellow, red, white, black or green.

Its moon Europa has a huge subsurface ocean.

Europa, the smallest of the four Galilean moons with a diameter of 3,121km (1,939mi), has an extremely smooth surface, beneath which lies a vast subsurface ocean of liquid water which astrobiologists believe may could harbour life.

Though if it does, we’re likely talking amoeba-like, single-cell organisms rather than little green men! In 2018, analysis of data provided by NASA’s Galileo probe, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003, confirmed that this ocean occasionally spews huge jets of water vapour out into space.

Jupiter is the vacuum cleaner of the Solar System

Due to its sheer physical size and mass, Jupiter exerts a very strong gravitational pull on any object that comes into its vicinity.

This means that smaller objects such as asteroids and comets that might otherwise have been heading Earth’s way are often sucked in – and smash into Jupiter instead. As a result…

It’s had to more impacts than any other Solar System body.

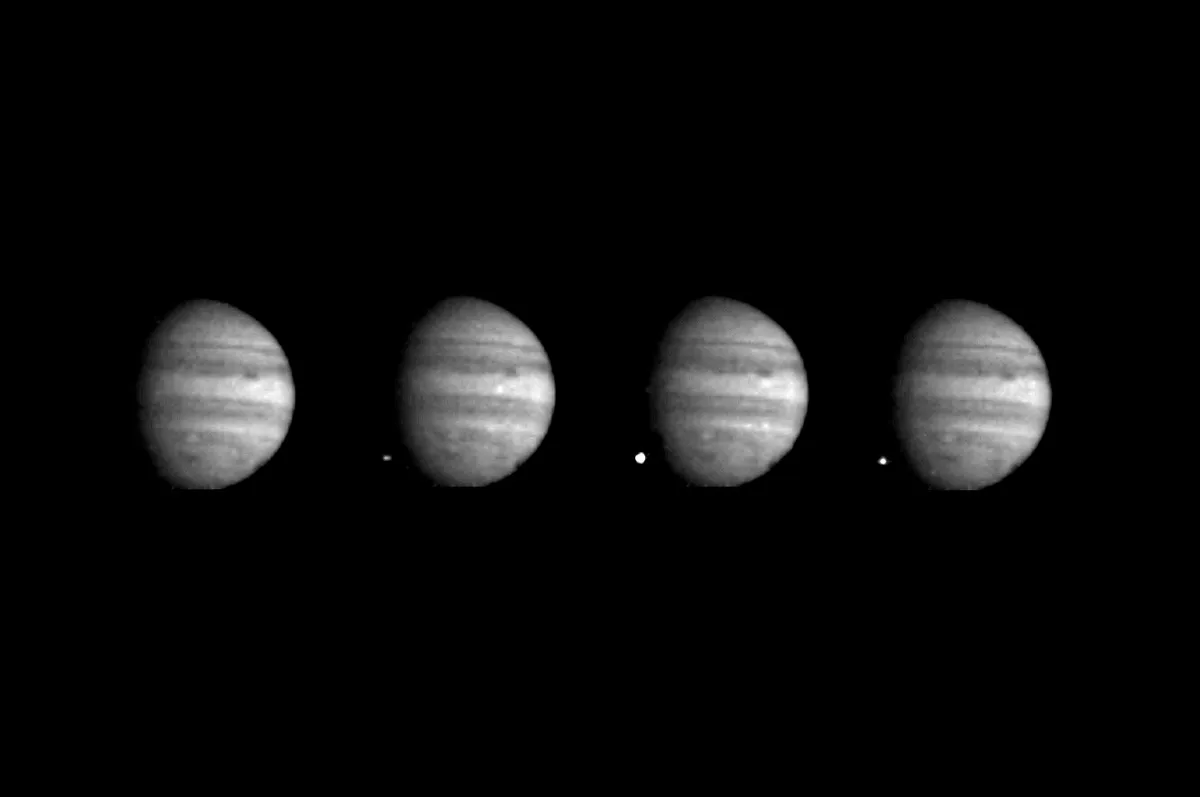

Comets and asteroids crash into Jupiter at around 200 times the rate at which they crash into Earth. Perhaps the best-known impact occurred in July 1994, when Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 collided with the planet in an event that was closely monitored by both the Hubble Space Telescope and NASA’s Galileo probe.

Jupiter helped shape the rest of the Solar System

Jupiter is such a behemoth that its gravity doesn’t just affect passing comets and meteors. It has had an influence on the other planets too, particularly early in the Solar System’s history.

Other than Mercury, the other planets’ orbits are closer to Jupiter’s orbital plane than they are to the equatorial plane of the Sun.

Most of its warmth doesn’t come from the Sun

Most planets in the Solar System are heated predominantly by the big, glowing star that sits at the heart of it.

But that’s not true in the case of Jupiter: its ongoing contraction generates more heat internally than it receives from its parent star.

Jupiter's moons form a mini 'planetary system' of their own

Jupiter has so many moons that they can almost be considered as a kind of mini-Solar System in their own right. Astronomers who study the complex interaction of these bodies and their parent planet call this the Jovian system.

The Galilean moons are clearly dominant here. In fact, the other 91 moons and the rings, put together, represent just 0.003% of all the mass that is in orbit around Jupiter.

Its atmosphere is mostly helium and hydrogen

Molecular hydrogen and helium make up roughly 76% and 24%, respectively, of Jupiter’s atmosphere – though it contains traces, too, of carbon, oxygen, sulphur, neon, ammonia and ammonium hydrosulphide (particularly in the troposphere), water vapour, phosphine, hydrogen sulphide and assorted hydrocarbons.

Jupiter's atmosphere is in four layers

Earth’s atmosphere has five layers: working outwards from the planet, these are the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere and exosphere. Jupiter, on the other hand, has no mesosphere.

The mesosphere is the layer of a planet’s atmosphere where gases are mixed together, as they are in the troposphere and stratosphere, rather than separating out into strata based on their molecular weight, as they do in the thermosphere and exosphere. But where temperature decreases with altitude (as it does in the troposphere) instead of rising (as it does in the stratosphere).

Jupiter is an oblate spheroid

All of the Solar System’s planets and most of its moons are oblate spheroids. Rather than being perfect spheres they look, in the words of astronomer Phil Plait, “like a basketball that someone has sat on”. This is because the rotation of the planets on their axes causes them to bulge outwards slightly at the equator.

But because Jupiter spins so fast it’s more oblate than most! Earth’s circumference at the equator is 0.3% larger than its circumference through the poles; the equatorial circumference of Jupiter, though, is 7 per% larger than its polar circumference.

It’s extremely unlikely to harbour life

While Jupiter’s moon Europa is thought to be one of the best places to look for signs of extraterrestrial life, the planet itself is an extremely hostile environment, whose pressure, temperature and chemical composition, put together, mean it would be pretty much impossible for life to exist there.

At least, any form of life that we could recognise as such.

It hasn’t always been where it is now

Jupiter lies around 5.2 AU (Astronomical Units) from the Sun. In other words, it’s 5.2 times further from the Sun than Earth is.

But according to the ‘grand tack hypothesis’, the current most-favoured model for Jupiter’s development, the planet originally formed around 3.5 AU from the Sun, then migrated inwards to 1.5 AU before drifting outwards again to its current position.

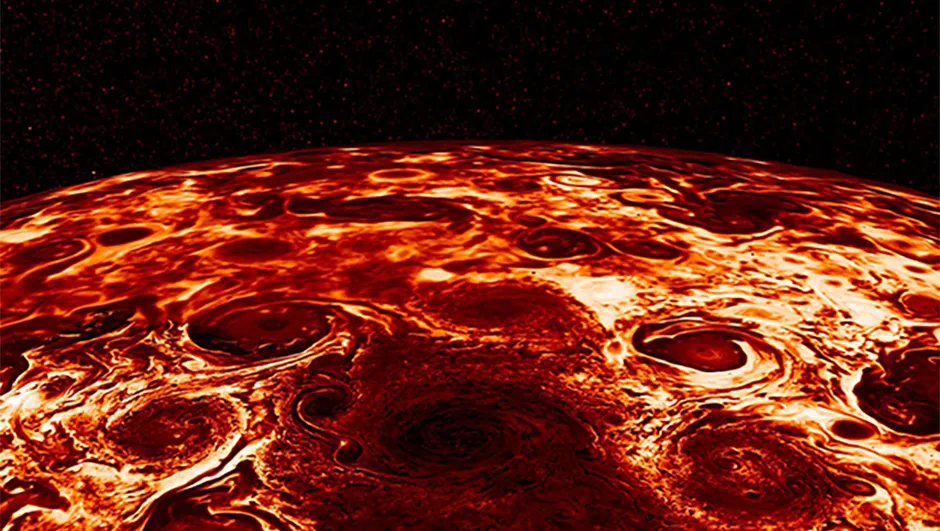

The Great Red Spot is by no means alone

The Great Red Spot may be Jupiter’s most famous dramatic weather event but it’s a long way from being only one.

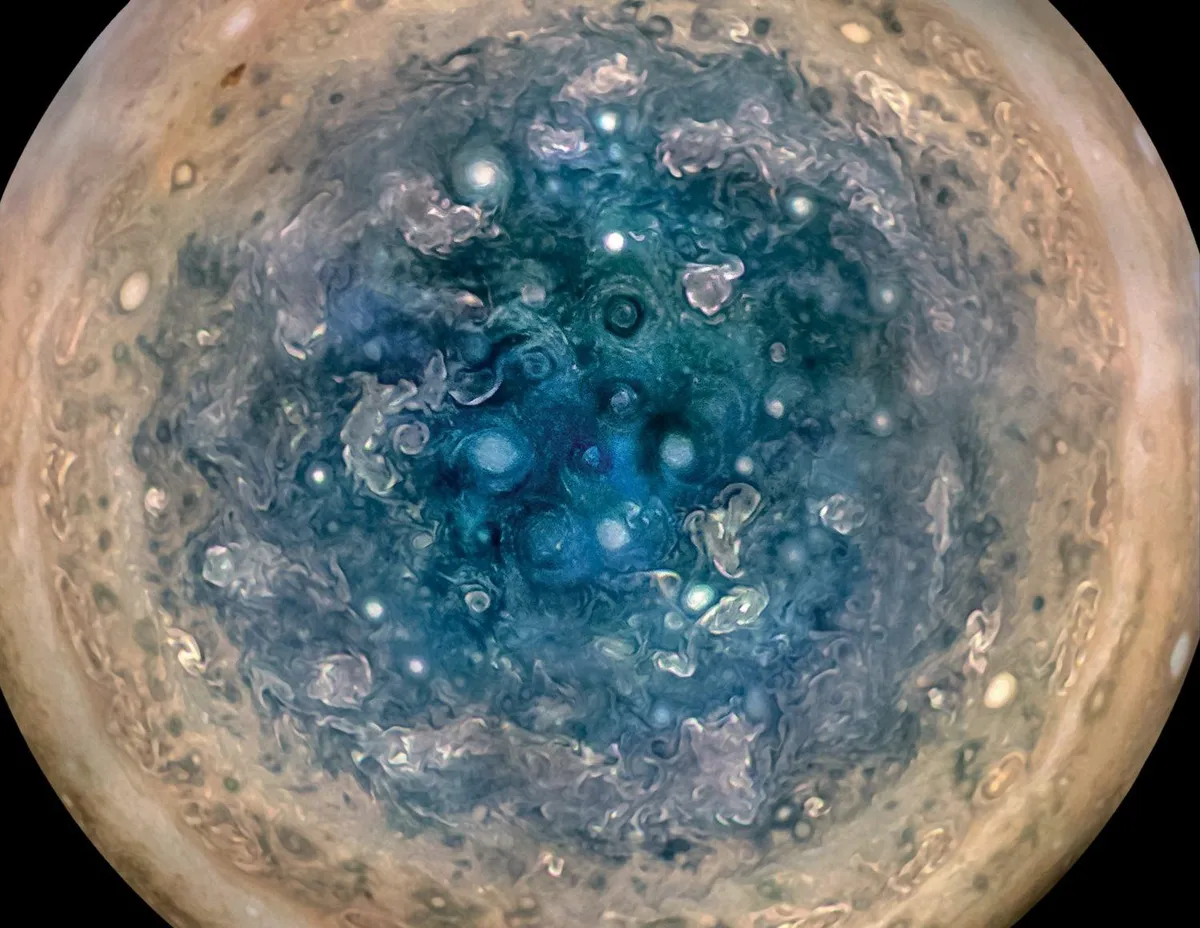

In fact, storms rage constantly throughout the planet’s atmosphere. The Juno mission, for instance, identified nine cyclones around the planet’s north pole and a further seven at its south pole, while since 2000 a GRS-like storm dubbed ‘Oval BA’ has been observed in the southern hemisphere.

Jupiter is a big emitter of radio waves

Under certain conditions, Earth sometimes receives more radio waves from Jupiter than from the Sun. This occurs because gases belched out by volcanoes become ionised by Jupiter’s magnetosphere, forming a plasma sheet that disrupts the planet’s magnetic field – causing energy to be transmitted outwards in a conical pattern.

When Earth passes through this cone, it is bombarded by radio waves. These waves have wavelengths measured in centimetres, and were first detected by Frank Drake and Hein Hvatum in 1959.

The first spacecraft to visit Jupiter were the Pioneer missions

NASA’s unmanned Pioneer 10 probe launched from Cape Canaveral on 3 March 1972, and sent back its first images of Jupiter on 6 November 1973.

Its closest approach to the planet occurred on 3 December 1973, when it came to within a distance of 132,252km (82,178mi). Pioneer 11 followed in Pioneer’s footsteps in December 1974, though unlike Pioneer 10, this probe carried on to Saturn as well.

Both Voyager probes flew past Jupiter

The next spacecraft to visit Jupiter were the two Voyager missions. Voyager 1 sent back images in the period January to April 1979, which was when the planet’s rings and Io’s volcanoes were first discovered.

Voyager 2 followed in July that year and identified three new moons: Adriasta, Metis and Thebe. It is debris from these three moons, plus Amalthea, that is thought to make up Jupiter’s rings.

In 1995, Galileo became the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter

Launched on the Space Shuttle in October 1989, the Galileo spacecraft arrived at Jupiter on 7 December 1995, and orbited the planet for seven years.

Problems with its antenna meant Galileo didn’t achieve all of its mission objectives, but it did capture the 1994 impact by Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, as well as firing a probe into the planet’s atmosphere, which travelled to a depth of around 150km (93mi) and sent back data for nearly an hour before being destroyed.

…and NASA then deliberately crashed it

No, the mission control crew weren’t experiencing a fit of rage caused by Galileo’s failed antenna! They simply wanted to ensure there was no chance of the craft crashing into Europa, due to the satellite’s status as a prime candidate for hosting extraterrestrial life.S

o instead they steered it into the planet on 21 September 2003.

The next mission to Jupiter was Juno

NASA’s Juno craft launched from Cape Canaveral on 5 August 2011 and arrived at Jupiter on 5 July 2016. This solar-powered probe was designed to study the planet’s gravity, magnetic field and magnetosphere.

By July 2018 it had completed 12 orbits, but its mission was extended until July 2021 – and in January that year it was extended again. The mission is currently expected to end in September 2025, when it too will be crashed into the planet.

Three other spacecraft have conducted Jupiter fly-bys

NASA’s solar probe Ulysses briefly flew by in 1992 and again in 2004, as did Cassini-Huygens on its way to Saturn in 2000.

But we learned the most from New Horizons. Although it was really on its way to Pluto, this 2007 mission was equipped with far more advanced cameras and equipment than previous missions, and so was able to send back much more detailed information, especially regarding atmospheric conditions and the planet’s magnetosphere.

New missions to Jupiter are all about the moons

Two spacecraft are currently on their way to the Jovian system. ESA’s Juice launched from French Guiana on 14 April 2023 and is expected to arrive in 2031. It’s there to study Callisto, Ganymede and Europa, hence the name (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer).

Meanwhile, NASA’s Europa Clipper – guess which moon that one’s headed to? – launched on 14 October 2024 and will arrive in 2030.

Transits of Jupiter by its moons are visible from Earth

If you have a telescope that’s capable of resolving Jupiter’s banded atmosphere and the Great Red Spot, then you should be able to see when its Galilean moons pass between Earth and planet, too.

Jupiter is our model for many other planets beyond the Solar System

The majority of the exoplanets discovered so far are so-called ‘hot Jupiters’. This means they’re of roughly similar size and composition to Jupiter, but orbit their parent star much more closely – as indeed Jupiter would, had it not migrated twice during its lifetime.

Studying Jupiter should therefore teach us much about planets in the wider Universe.

What are your favourite facts about Jupiter? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.co.uk