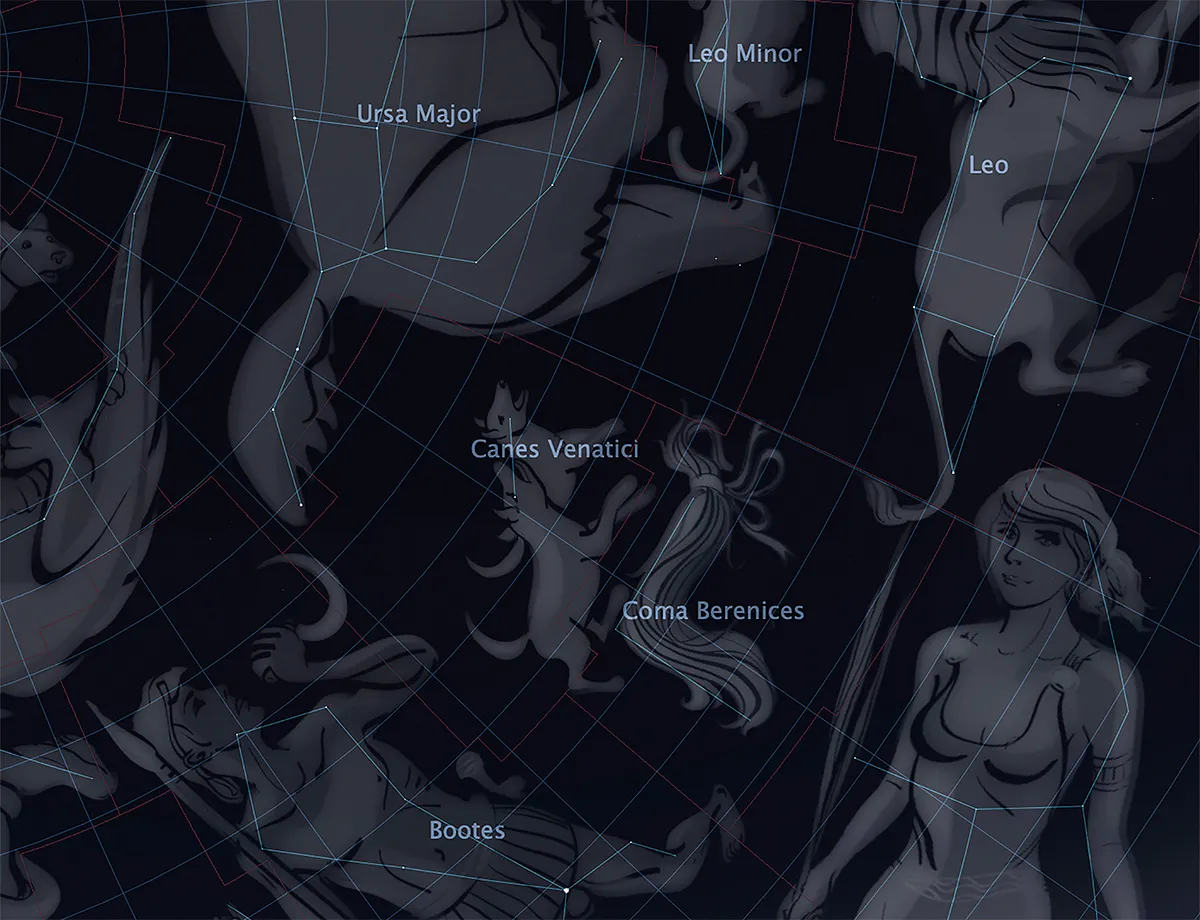

Two dogs snap at the heels of the Ursa Major, the Great Bear, in a nightly chase around the north celestial pole. These canines are the hunting hounds of Boötes, the Herdsman, who holds them on a leash in his outstretched hand.

In Greek tradition, Boötes was visualised in several ways, usually herding or driving animals.

One story says that the name Boötes comes from the Greek for ox driver, since the stars of the Plough were visualised as an ox cart.

An alternative explanation is that the name comes from a Greek word meaning ’noisy’, and we can perhaps imagine the sounds of the herdsman shouting to his animals in the night.

- Read more about the history of astronomy

The two dogs of Boötes are represented by the constellation of Canes Venatici, but this isn’t one of the 48 figures that the ancient Greek astronomer Ptolemy listed in his great source book, the Almagest, written around 150 AD.

Unlike the modern constellations, which fit neatly together, the Greek constellations didn’t fill the entire sky.

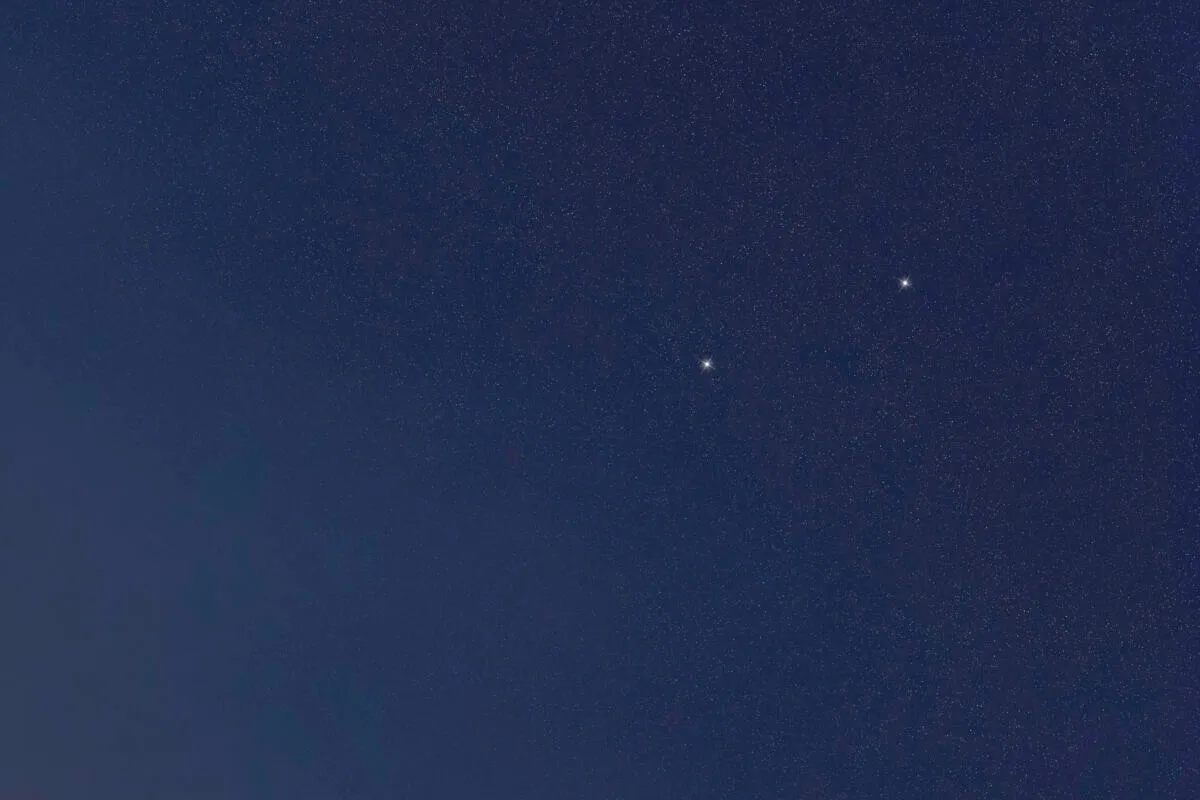

Between Boötes and Ursa Major was a large gap. Within it were two stars, which Ptolemy had classed among the ‘unformed’ stars outside Ursa Major, not part of any constellation and so free to use in a new figure.

The brighter member of this pair of stars is known as Cor Caroli (Alpha (α) Canum Venaticorum) or ‘Charles’s Heart’, a name given to it by British astronomers in the 17th century, before Canes Venatici was formed.

How this name came about is a story in itself.

Cor Caroli – the heart of King Charles

Before Boötes acquired his canine companions there was another mini-constellation in this area known as Cor Caroli, Charles’s Heart.

The poet Edward Sherburne (1616–1702) wrote in his translation of The Sphere of Marcus Manilius that the name was “…in Memory of the most Glorious Prince and Martyr, Charles the First”, and that the King’s physician, Sir Charles Scarborough, had come up with the idea.

According to historian Deborah Jean Warner, the name first appeared in print in 1673 on the northern half of a pair of celestial hemispheres by the cartographer Francis Lamb.

He labelled the star Cor Caroli Regis Martyris (‘Heart of Charles the Martyred King’) – Charles I had declared himself “the martyr of the people” at his 1649 execution.

On his chart, Lamb drew a heart and crown around the star, making it a mini-constellation. Sherburne followed suit, as did instrument maker Thomas Tuttell.

In his Bedford Catalogue of 1844 WH Smyth stated it was named Cor Caroli by Edmond Halley, at the suggestion of Scarborough after he noticed a star, which Johannes Helvelius had made part of Chara’s collar, was shining brighter than usual on the night before Charles II returned to London.

Smyth gave no source for this assertion, which, as well as being astronomically unlikely, compounds three errors:

- the star wasn’t named by Halley

- it was named before Hevelius had created Canes Venatici

- the name doesn’t refer to Charles II

However, Smyth can claim he was misled about Halley and Charles II because he was repeating what Johann Bode had said (wrongly) in an 1801 star catalogue.

Could such a brightening have really happened? Cor Caroli is slightly variable, but its fluctuations are too small for the naked eye. The possibility that it should have brightened on the night of Charles II’s return is undoubtedly apocryphal.

Where did Canes Venatici originate?

The prime mover behind the introduction of the constellation of Canes Venatici, the Hunting Dogs, to the sky was Johannes Hevelius (1611–87), a wealthy brewer from Danzig, (now Gdańsk, Poland), who was one of the greatest observers of his age.

He used his wealth to create a rooftop observatory equipped with top-quality instruments of his own construction.

His interests were wide-ranging and his output prolific: he observed sunspots, comets and the variable star Mira (Omicron (ο) Ceti) – which he named, plus a transit of Mercury, the moons of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn.

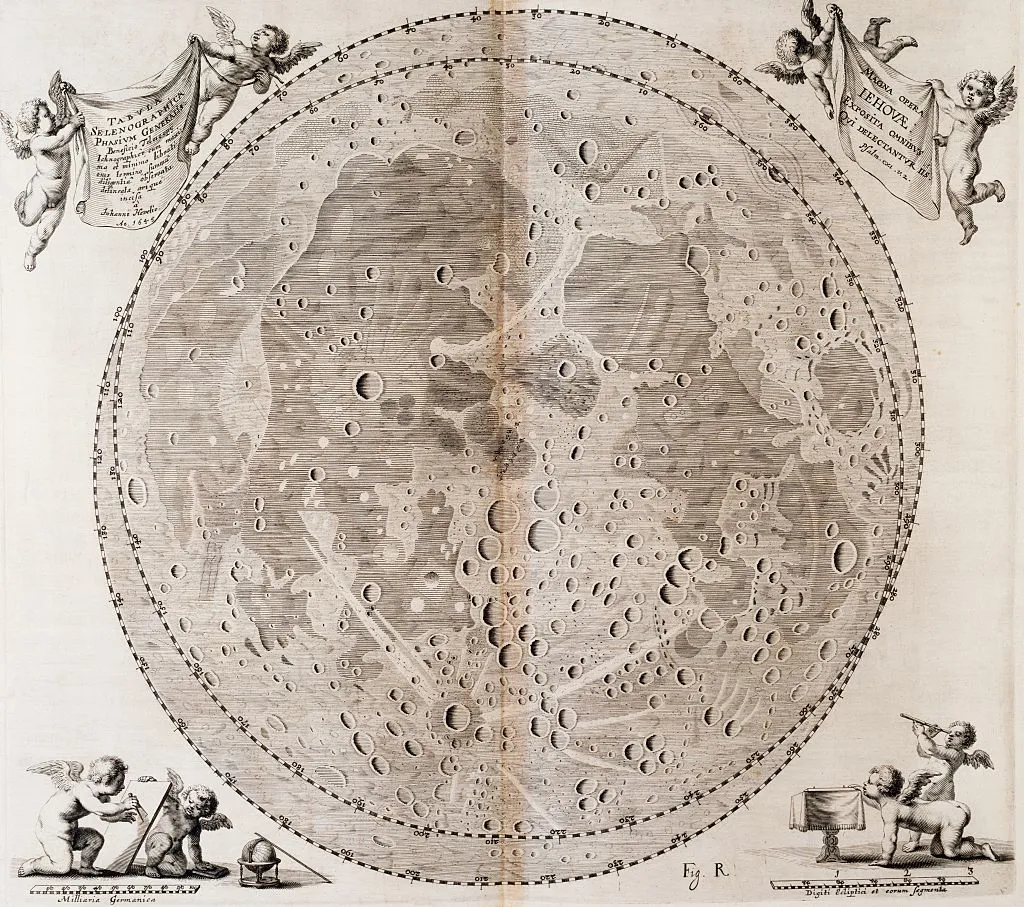

He also produced the first atlas of the Moon, Selenographia. Like his hero Tycho Brahe (1546–1601), Hevelius published his results on his own printing press.

The underlying aim for much of his life, though, was to improve on Tycho’s catalogue of a thousand stars.

Had he wished, Hevelius could have produced the first-ever star catalogue made with a telescope, ahead of John Flamsteed at Greenwich, but he was concerned that lenses might introduce positional distortions.

Instead, he relied on simple naked-eye sighting instruments, such as sextants and quadrants similar to those used by Brahe in pre-telescopic days.

Hevelius claimed that their quality and his sharp eyesight were a match for smaller instruments with telescopic sights.

This brought Hevelius into conflict with the Royal Society, which had elected him as a member in 1664.

Robert Hooke, in particular, doubted that his results would be a match for telescopic measurements, but Hevelius disagreed.

To resolve the issue, Edmond Halley went to visit Hevelius and observed alongside him using a quadrant with telescopic sights.

Hevelius was a brewer and Halley liked a glass of ale, so the two got on famously and, upon his return, Halley was happy to endorse the accuracy of Hevelius’s results.

Subsequent analysis has shown that his star positions were indeed more accurate than Brahe’s.

The Catalogus Stellarum Fixarum (‘Catalogue of Fixed Stars’) by Hevelius contained over 1,500 stars, 50% more than either Ptolemy or Brahe had recorded, giving him plenty of raw material from which to fashion new constellations in the gaps between the ancient figures.

The catalogue was in the process of being printed in 1687 when Hevelius died. It was seen through to publication by his wife Elisabeth, eventually appearing in 1690 along with a magnificent atlas, Firmamentum Sobiescianum, named in honour of the Polish king, John III Sobieski.

Along with the Ptolemaic figures, the catalogue and atlas of Hevelius contained 10 constellations of his own devising, seven of which we still use today: Canes Venatici, the Hunting Dogs; Lacerta, the Lizard; Leo Minor, the Smaller Lion; Lynx; Scutum, the Shield; Sextans, the Sextant; and Vulpecula, the Little Fox.

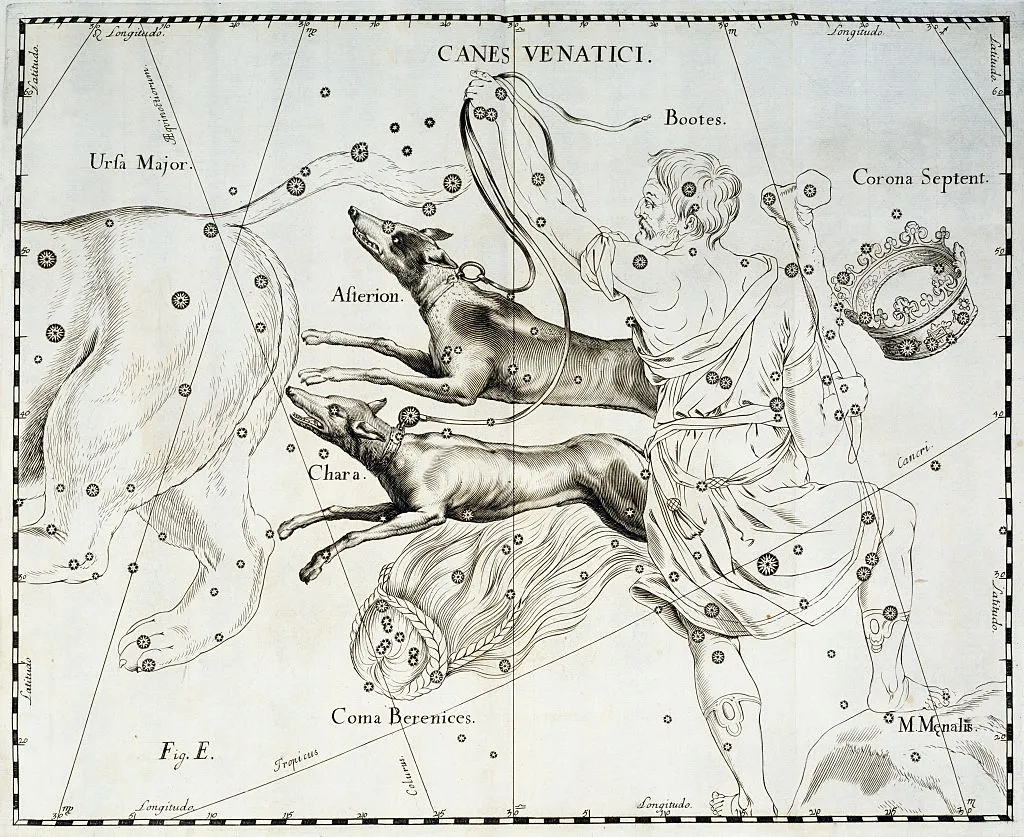

The depiction of Canes Venatici by Hevelius can be seen in his 1690 atlas (pictured above).

As on all of his charts, the constellation is drawn as it would appear on a globe, so it appears back-to-front compared to the way we see it in the sky.

The dogs are meant to be greyhounds, which hunt as a pair, although they might not look like it the way they’re drawn on some charts.

Hevelius named the northern dog Asterion and the southern one Chara (he deemed them to be male and female respectively).

Chara, leading the chase, is clearly the top dog as she contains the two unformed stars listed by Ptolemy, of third and fourth magnitude, now known as Alpha (α) Canum Venaticorum and Beta (β) Canum Venaticorum.

These designations were allocated by the English astronomer Francis Baily in his Catalogue of Stars of the British Association for the Advancement of Science of 1845, since Hevelius didn’t use Greek letters on his charts.

Alpha (α) Canum Venaticorum is Cor Caroli. By contrast, Chara’s kennel-mate Asterion is marked by only a scattering of faint stars.

Although Hevelius is rightly credited with the invention of the constellation of Canes Venatici, he was not the first to show dogs in this area.

That honour goes to the German astronomer Peter Apian (Petrus Apianus in Latin) who published a star chart showing Boötes with two dogs in 1533, 150 years before Hevelius.

Three years later, on another of Apian’s charts, the number of dogs had grown to three.

Was Boötes a dog owner?

Where did Apian get the idea that Boötes might be a dog owner? Certainly not from Greek myth, as there’s no mention of canine companions there.

The star name expert Paul Kunitzsch has traced the origin of the idea to a bizarre mistranslation in the 12th century.

Gerard of Cremona, who was retranslating an Arabic-language version of the Almagest into Latin, apparently mistook the Arabic word al-kullāb, referring to the shepherd’s crook carried by Boötes, for al-kilāb, which means dogs.

He ended up with a garbled phrase implying that Boötes carried a staff with dogs. Apian evidently read this incorrect translation and added the dogs to his Boötes image.

Apian’s dogs can’t really be considered forerunners of Canes Venatici since, unlike the greyhounds of Hevelius, they were still following Boötes and not the Great Bear.

What’s more they didn’t incorporate any of Ptolemy’s stars.

A more plausible prototype appeared on a celestial globe of 1602 made by the eminent Dutch cartographer Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571–1638).

On this we see Boötes holding two dogs that are following the Great Bear (pictured above), as in the constellation of Hevelius.

The lead dog is marked by Beta Canum Venaticorum and the follower by Cor Caroli. This was the first attempt to incorporate the two brightest stars in this area into a pair of dogs, although Hevelius achieved it differently by allocating both stars to Chara, the southern dog.

Did Hevelius take his idea from Blaeu’s globe? He didn’t say, but the similarity between Blaeu’s dogs and the later constellation of Hevelius is striking.

Perhaps the history of the constellations should be revised to give Blaeu a share of the credit for the formation of Canes Venatici.

Next time you’re out, see if you can spot these two leaping greyhounds, and the heart of King Charles, in the space between Boötes and the Great Bear.

Canes Venatici is also the location of TON 618, one of the biggest known black holes.

This article originally appeared in the December 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.