Autumn astronomy is a phrase that many night-sky observers love to hear, as summer comes to an end.

The start of autumn in the Northern Hemisphere means the nights get longer, darker and earlier.

A new astronomy season is upon us, and there a numerous exciting sights we can look forward to seeing as the dark-sky season begins.

Let's take a look at some of the best astronomy and stargazing targets to see throughout autumn 2021: indeed, into winter and the new year.

For more advice, read our guides to the best autumn constellations, Patrick Moore's top 5 autumn galaxies and top autumn binocular targets

September

With September here, the long summery days are gradually changing into early nights. The autumn astronomy season has begun.

We’ll see spring and summer’s stars making way for the dark-sky season as autumn approaches.

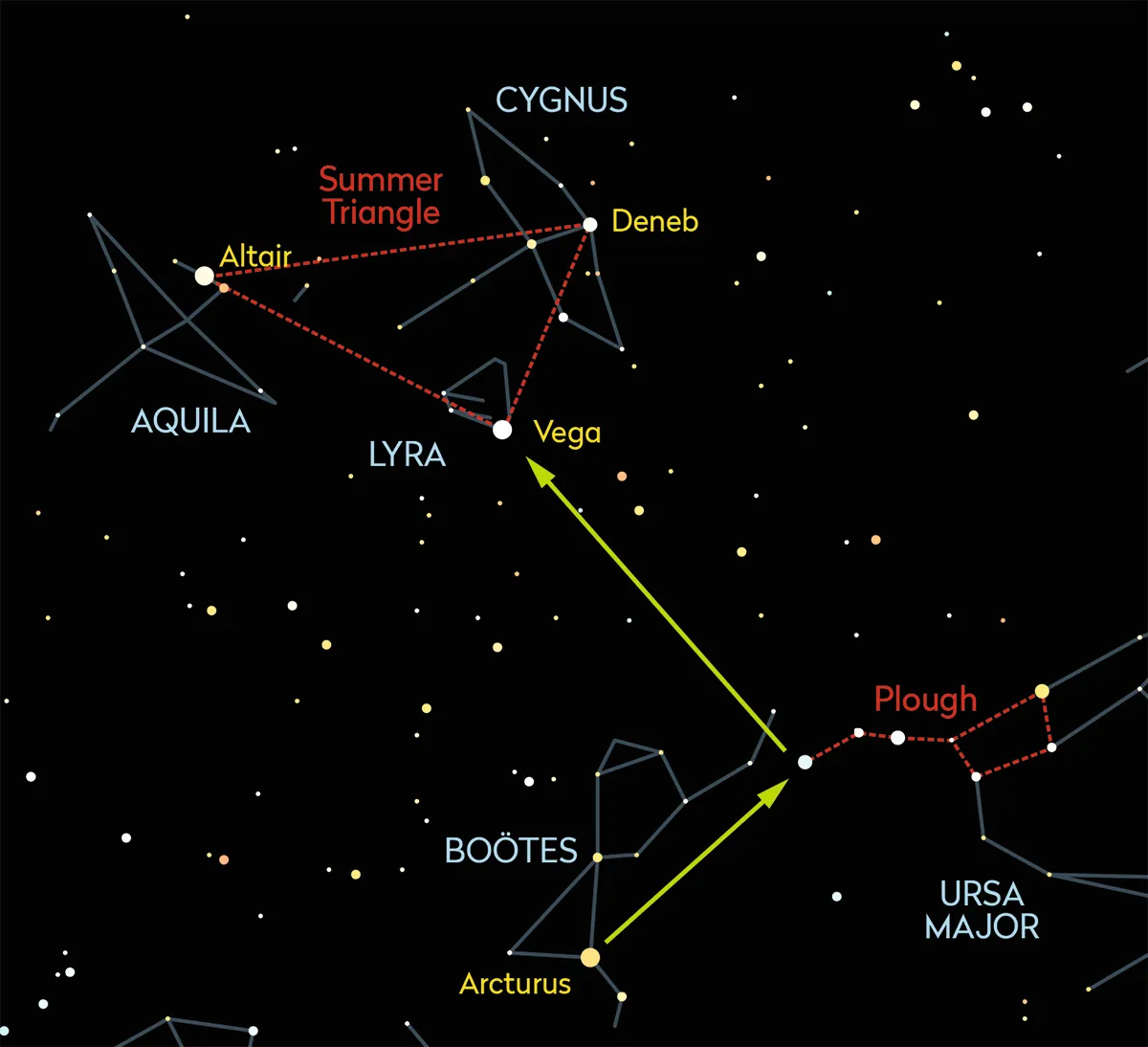

Let’s begin our dark-sky adventure at a well-known asterism, the Plough, sitting upright just above the northern horizon.

The next bright star to its south-southeast is Arcturus (Alpha (α) Boötis), which we usually think of as a springtime star.

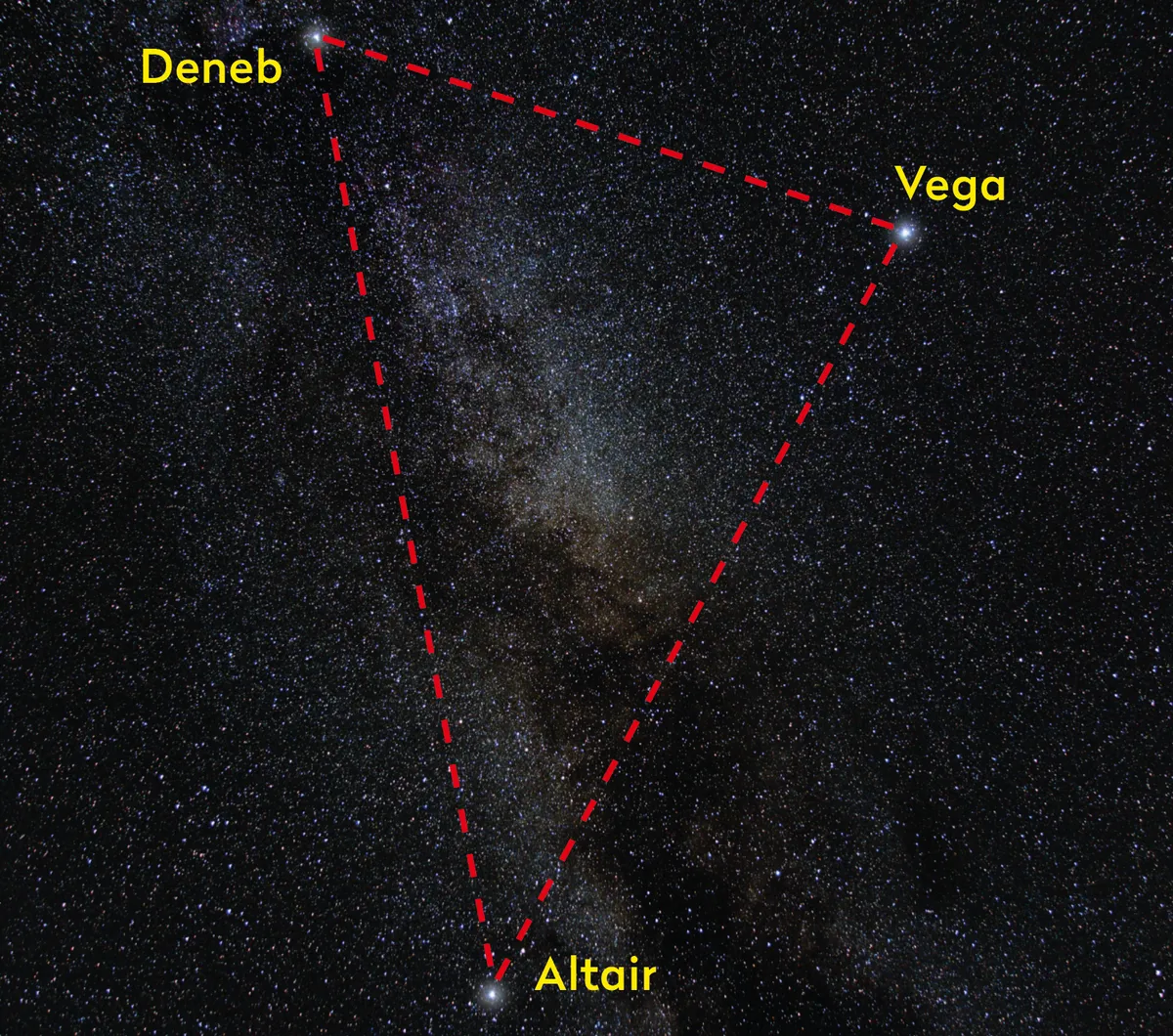

Next, high overhead, we find the Summer Triangle’s stars: Vega (Alpha (α) Lyrae), Altair (Alpha (α) Aquilae) and Deneb (Alpha (α) Cygni), and then drop towards the east for the Great Square of Pegasus.

Maybe we can spot Capella (Alpha (α) Aurigae), just above the northern horizon.

With binoculars, let’s look for the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, just to the northeast of Pegasus, the Winged Horse, and then the Double Cluster in Perseus, the Hero a bit further northeast.

October

With the autumn equinox behind us, in October there’s more night than day now for the first time since March, and it’ll stay that way until March next year.

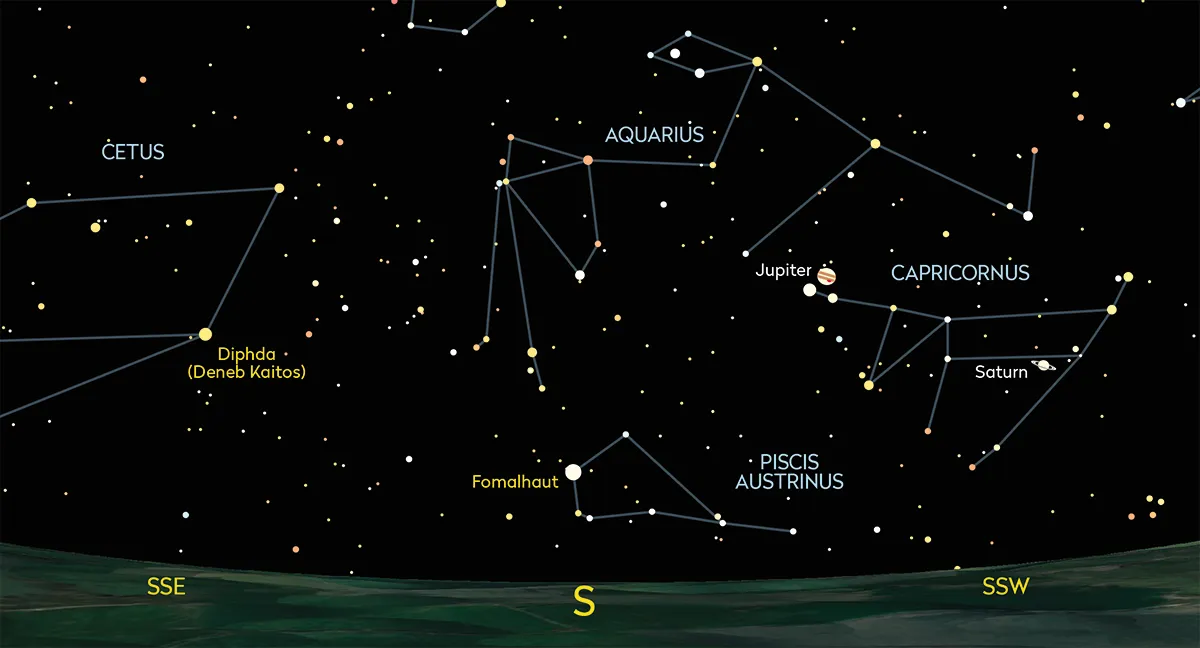

Fomalhaut (Alpha (α) Piscis Austrini) is almost due south at mid-evening. It’s the southernmost first-magnitude star we can see in the Northern Hemisphere, in a part of the sky without many other bright stars.

With so little happening nearby, it appears as a slightly oddball light a few degrees above the horizon. Diphda (Beta (β) Ceti), also known as Deneb Kaitos, is about 25° east of Fomalhaut.

The starry constellation of Cassiopeia, the Queen is high overhead with Cepheus, the King to its west, Perseus, the Hero to its east and the Milky Way running through them all.

The peak of the Orionid meteor shower takes place on the night of 21/22 October.

November

Deeper into autumn astronomy season, the Plough is low above the northern horizon.

Arcturus has departed now, but let’s follow the line between Megrez (Delta (δ) Ursae Majoris) and Dubhe (Alpha (α) Ursae Majoris), across the top of the blade to Capella, whose golden colour is stunning on these stark nights.

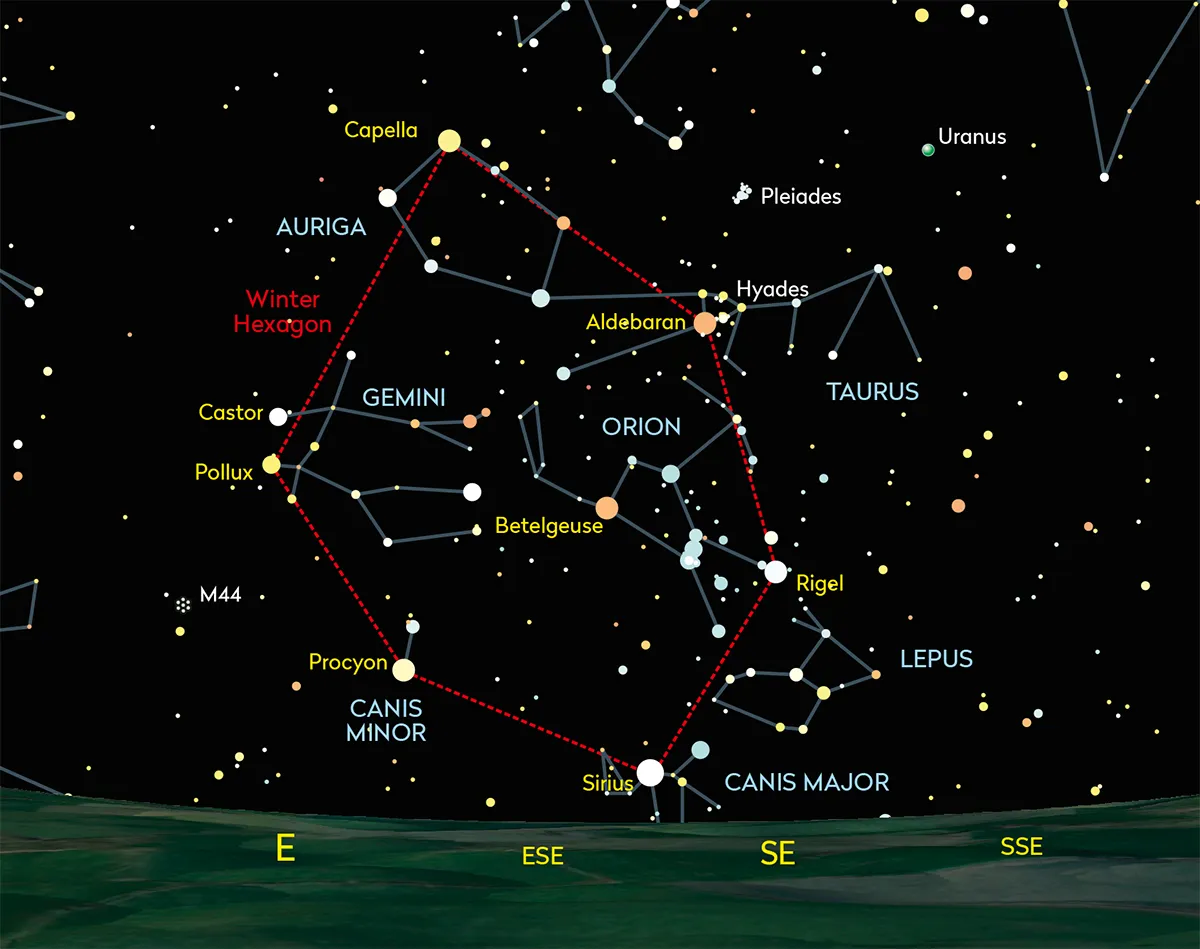

Widening our gaze, we can see most of the Winter Hexagon: the asterism of six of the sky’s brightest stars.

There's one star each in six constellations, covering a patch of sky so enormous that the Moon needs four nights to cross it.

Anti-clockwise around it are Capella, then Pollux (Beta (β) Geminorum), Procyon (Alpha (α) Canis Minoris), Sirius (Alpha (α) Canis Majoris), Rigel (Beta (β) Orionis), and Aldebaran (Alpha (α) Tauri).

Aldebaran marks the southeast end of the southern arm of the V-shaped Hyades, with the tiny, dipper-shaped Pleiades a short hop away.

They’re among the closest star clusters to us, about 150 and 450 lightyears away respectively.

They’re truly stunning in binoculars and worth observing for a good, long time. Aldebaran isn’t part of the cluster, but it sits about halfway between the Hyades and Earth.

With binoculars look for the Hyades open cluster in Taurus, the Bull.

December

As our autumn astronomy season comes to an end, we welcome the onset of winter.

The start of winter is just three weeks away now, with the winter solstice on 21 December, so these are the year’s longest nights.

With sunset before 16:00 UT these are my favourite nights for observing in the year. Indeed, let’s spend a little extra time simply soaking in that extra darkness without any worry about which star is which.

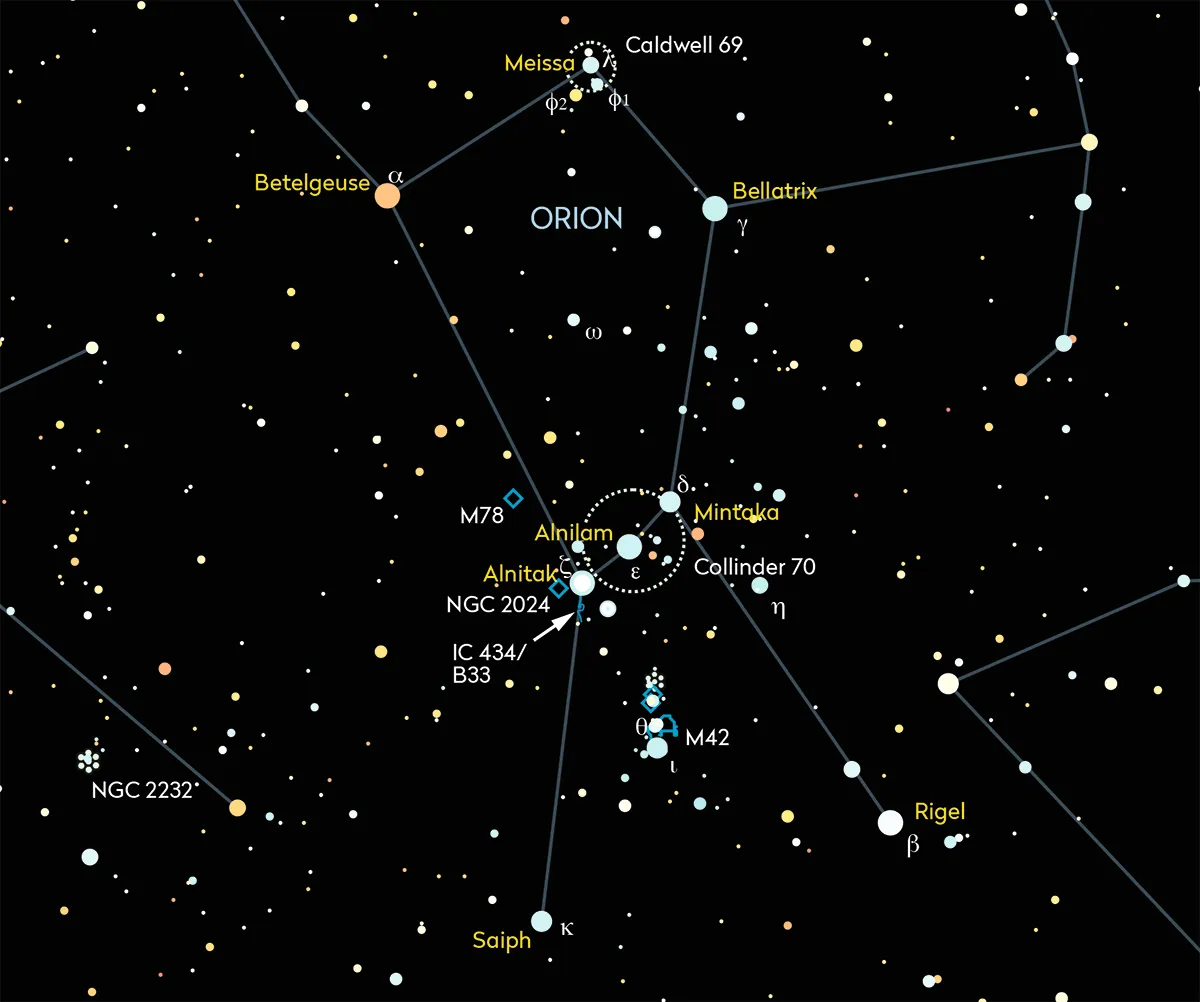

This is also the start of Orion season! All of the Hunter’s seven famous stars are above the southern horizon by mid-evening, but can you remember their names?

The red supergiant Betelgeuse (Alpha (α) Orionis), and Bellatrix (Gamma (γ) Orionis) are his shoulders. Saiph (Kappa (κ) Orionis), and icy blue Rigel are his feet.

The belt stars are Alnitak (Zeta (ζ) Orionis), Alnilam (Epsilon (ε) Orionis), and Mintaka (Delta (δ) Orionis).

Let’s visit them as they rise a little earlier each night and make their way a little further to the west at the same time each night.

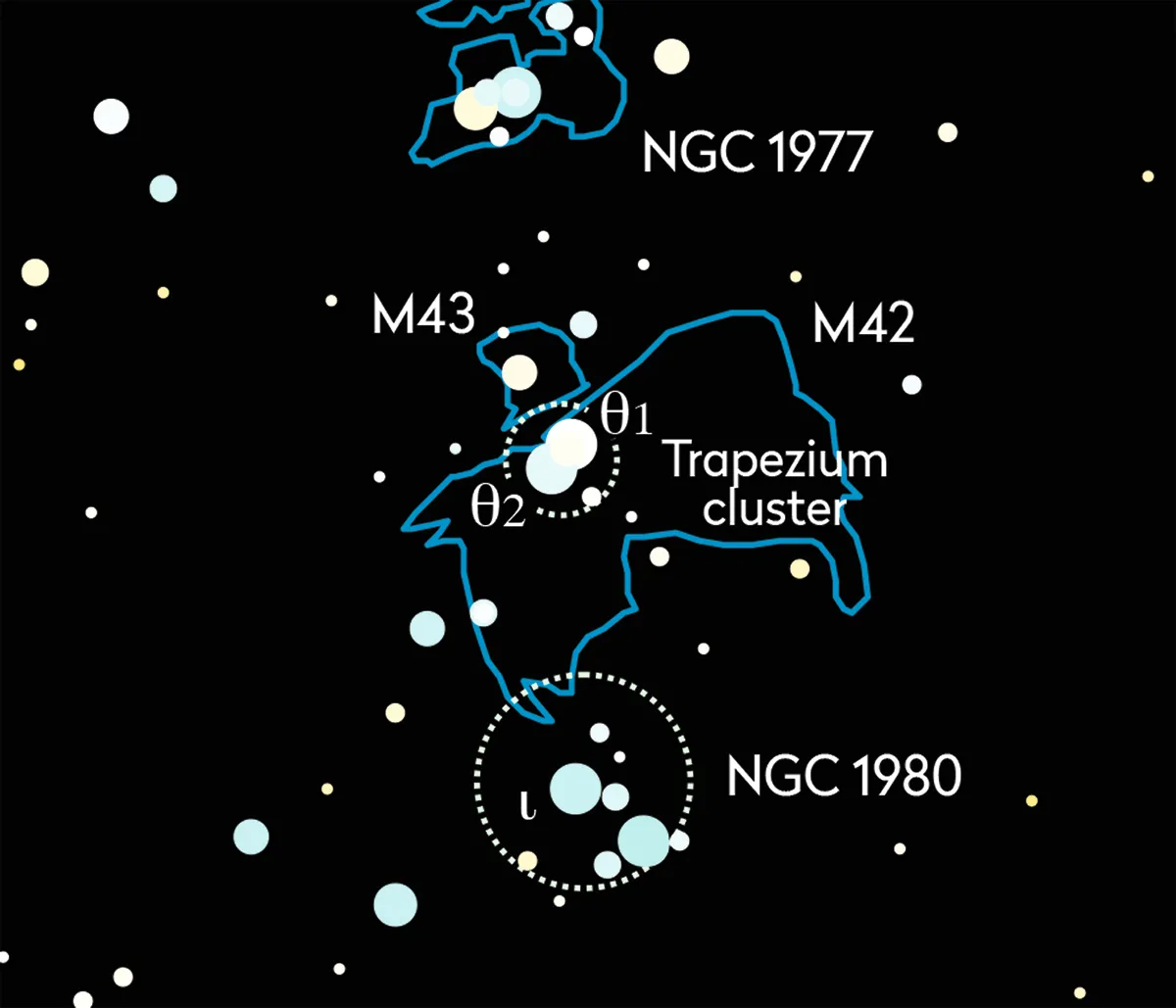

Many of us also know the Orion Nebula; the star-forming region in the middle of his sword, with the Trapezium Cluster deep within it.

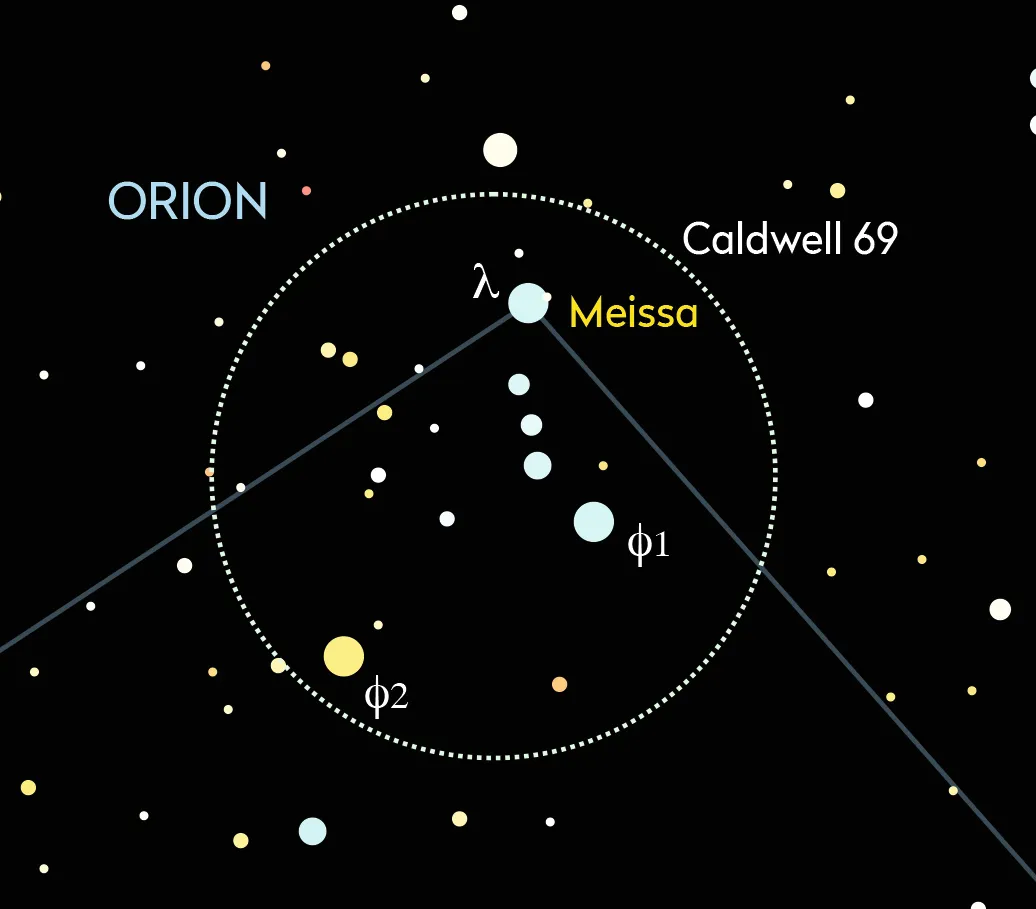

Let’s look at his head too; Meissa (Lambda (λ) Orionis) is the brightest star in the Caldwell 69 open cluster.

With binoculars, we can see a dusty glow there, as well as a beautiful ladder of three stars extending from Meissa.

Orion’s Belt is also part of a glowing cluster, Collinder 70, with the Horsehead and Flame Nebulae nearby (Barnard 33 and NGC 2024).

The first of these targets is a challenge, needing a large scope and dark skies.

Also this month, the Geminid meteor shower peak occurs on 13/14 December with a ZHR of 120.

January

Happy New Year! Having passed the winter solstice on 21 December, the nights are slowly shortening.

We’re six months from summer now. If you can believe it, the Summer Triangle is still with us. It’s spent that time crossing high overhead, and now its stars call to us through the wintry western dusk.

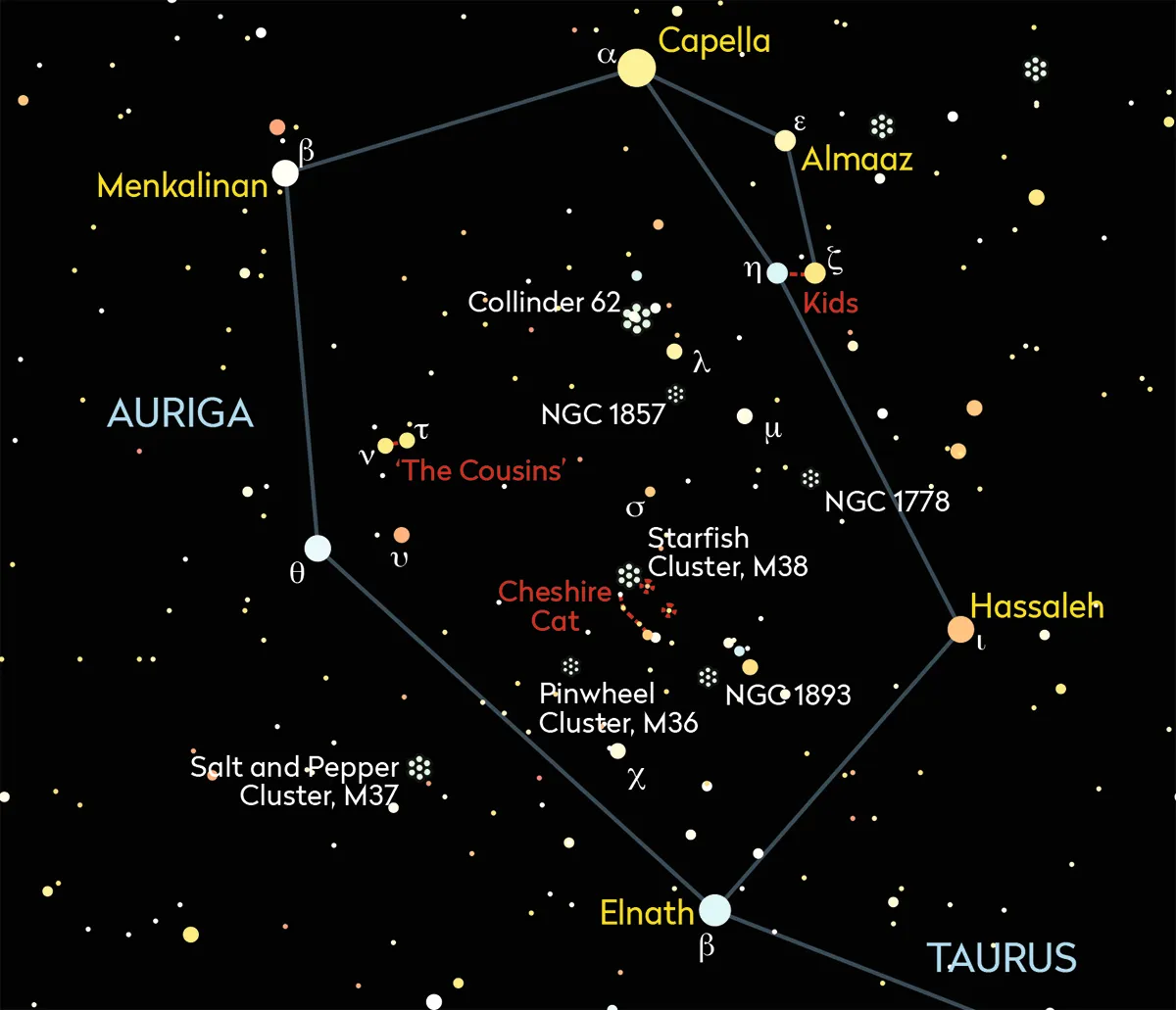

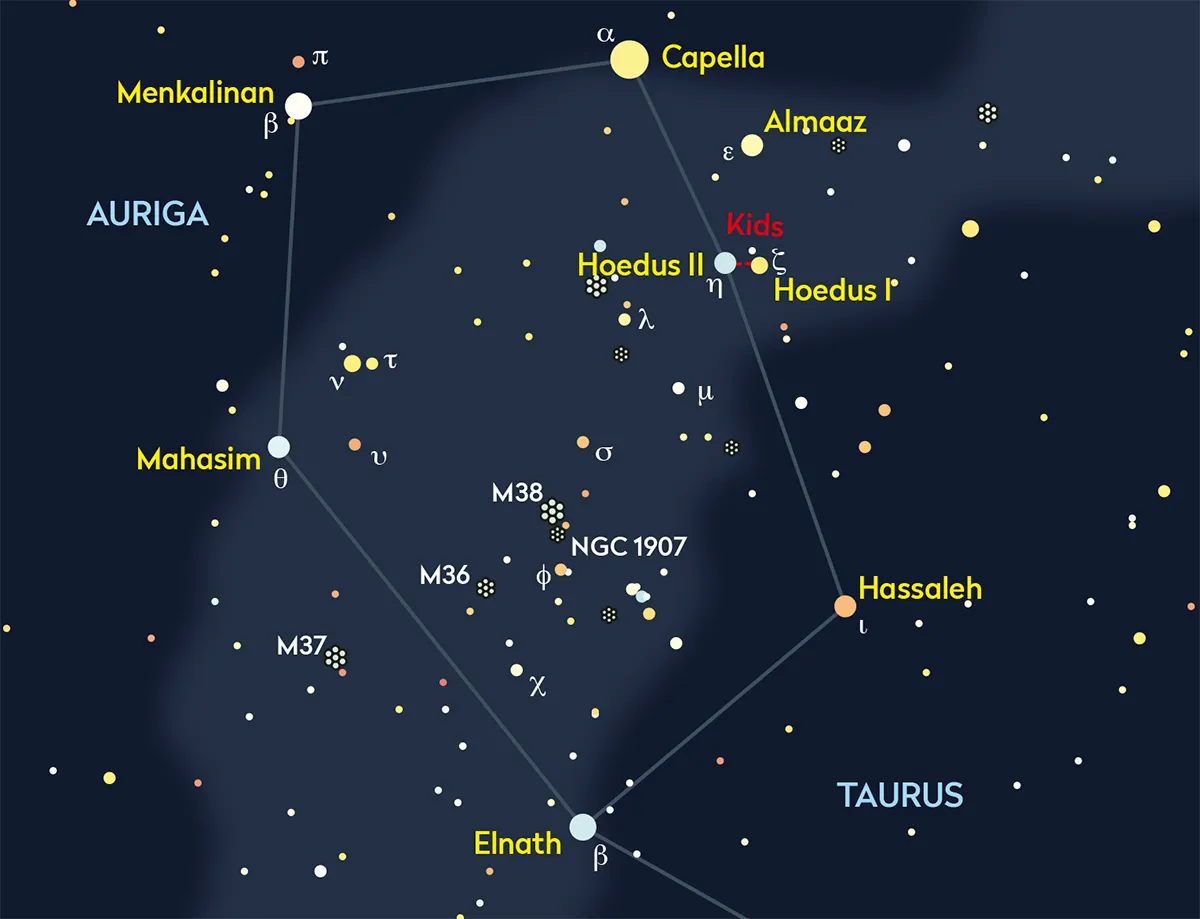

The constellation of Auriga, the Charioteer is high towards the south in January.

Use binoculars to search for the open clusters M36, M37 and M38 in the constellation of Auriga, the Charioteer.

Its brightest star Capella has the nickname ‘The Goat Star’, so let’s look for the pair of stars called The Kids, about 5° to its south.

With binoculars, we can scan the distant star clusters scattered through the constellation, including the Pinwheel, Salt and Pepper and Starfish Clusters (M36, M37 and M38).

About 10° west of Capella, we’ll find Menkalinan (Beta (β) Aurigae), with another, almost-matching pair, which I call ‘The Cousins’, about 5° to its south.

The balance and symmetry of these is something I look forward to all winter.

Let’s also see if we can spot some small star chains sprinkled among them.

Mirfak (Alpha (α) Persei) and the Alpha Persei Cluster, about 20° to the west of Capella, are also an amazing sight through binoculars.

February

We’ve come to the last full month of the dark-sky season. The Sun sets an hour later at the start of the month than it did at December’s solstice, and we’ll see another additional hour of daylight by the end of the month.

All of Canis Major, the Great Dog is above the southern horizon by mid-evening now.

The ‘Dog Star’, Sirius (Alpha (α) Canis Majoris), culminates – appears at its highest position, due south – at 21:00 UT by mid-month.

Around this time we’ll notice that Arcturus has sneaked back into the night. Its welcoming red glow is a sign that even though we feel the nights shrinking, spring is on its way.

Betelgeuse culminates at 21:00 UT early in the month. With Orion standing tall above the horizon, it’s a great moment to rewind our minds and remember a few months ago.

Back then, those stars were just climbing into the eastern sky as the last of the leaves fell to our feet. Before long, Orion will fall into the dusk as new buds pop onto the trees.

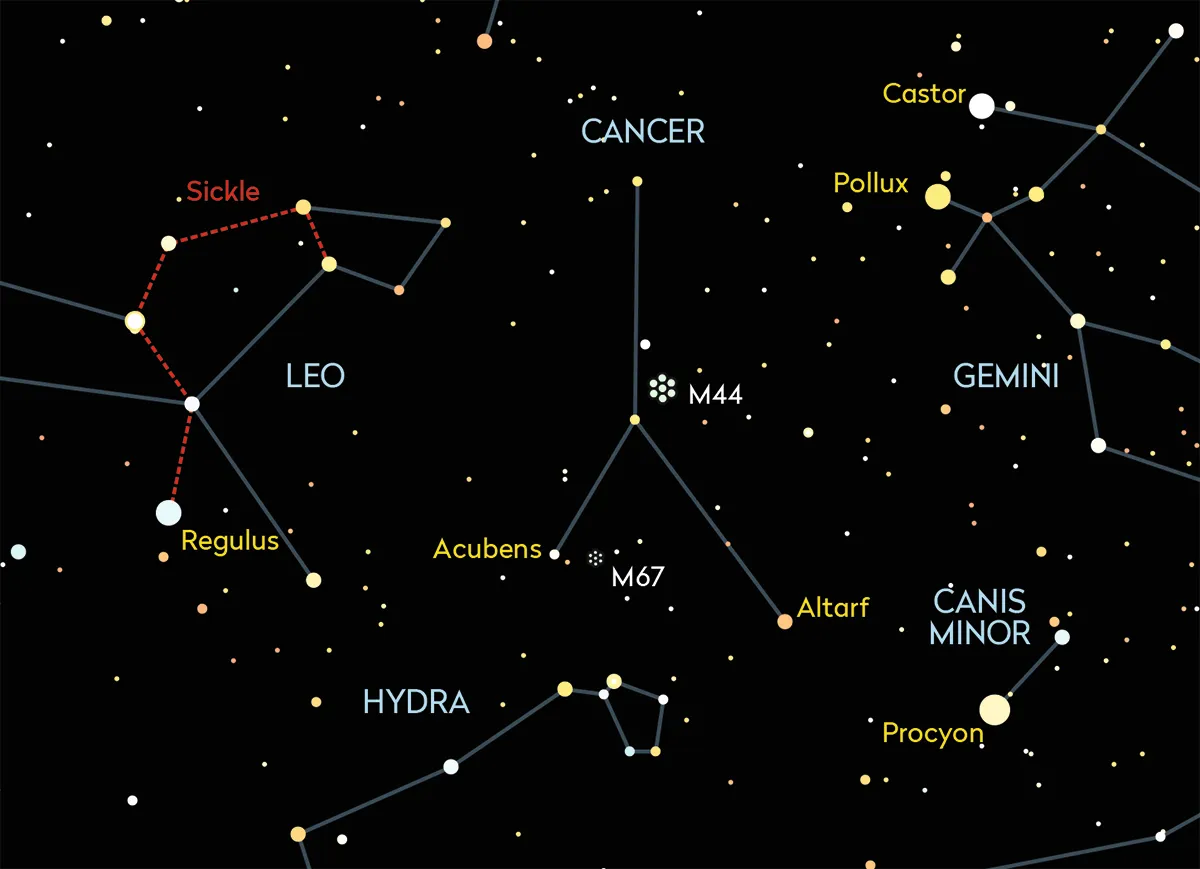

If we search through the dim constellation of Cancer, the Crab, in the patch of sky between Gemini, the Twins and Leo, the Lion’s ‘Sickle’, we’ll find the Beehive Cluster’s thousand stars.

Mornings are the best time for spotting planets this month. Venus, as it so often does, will stop us in our tracks, glowing just before sunrise.

There’s more than enough to keep any astronomer busy all the way through the dark-sky season until next spring.

5 targets for the dark-sky astronomy season

Milky Way delights

Early on in September we can still see the Milky Way stretching up across the sky, starting with the centre of our Galaxy almost due south at the end of twilight.

Here we have gorgeous summer objects such as the Lagoon Nebula (M8), the Trifid Nebula (M20) and the Omega Nebula (M17), while star clouds and clusters such as M24 and the Wild Duck Cluster (M11) cry out to be viewed.

Summer Triangle

Higher up towards the zenith all three members of the Summer Triangle asterism – bright stars Deneb, Vega and Altair – remain on view well into December.

Bounded within this triangle is the stunning planetary nebulae the Dumbbell Nebula (M27) and the Ring Nebula (M57). If you enjoy double stars and multiple stars, Albireo in Cygnus should be on your observing list.

Its golden yellow and sky blue components are easily resolvable with a small telescope.

Dark nebulae

Engrossed in the splendours of our Galaxy, it is easy to overlook dark nebulae.Look along the Milky Way towards Cygnus and note the split in the Milky Way.

This is the Cygnus Rift; a huge cloud of interstellar dust obscuring our view of background stars.Cosmic dust like this lies in the plane of our Galaxy and so gives rise to many dark patches that are worth looking out for.

Globular clusters

If you can pry your gaze from our Galaxy, take a look at the multitudes of globular clusters that surround it in a halo.For us this extends from Scorpius up into Serpens, Ophiuchus, Hercules and down into Capricornus, Aquarius and Sagittarius.

These incredibly distant objects, several thousand lightyears away, include such gems as M13 and M92 in Hercules, M5 in Serpens, and M22 and M28 in Sagittarius.

Through small telescopes they often look like little cotton balls.

Late autumn targets

As we move into October and November, the constellations of Aquarius and Capricornus become better placed over in the south, rich with promising targets.

Pick off the final batch of globular clusters such as M30, M2 and M72, along with M15 up in Pegasus.Seek out the faint but large Helix Nebula and the Saturn Nebula, two planetary nebulae in Aquarius.

For more, read our observing guide 6 planetary nebulae to spot in the night sky.

Winter astronomy targets

From October until the end of the year the final glories of the autumn skies come into view, taking us into the more distant reaches of space.

Pegasus has the often overlooked galaxy NGC 7331, while close by lies the more challenging Stephan’s Quintet of galaxies. This is prime time for galaxies as the Andromeda Galaxy and the Triangulum Galaxy move into sight.

Pick a clear, transparent night, head to a dark sky area and let your eyes become properly dark adapted (it takes about 40 minutes) to stand the best chance of seeing the farthest objects it is possible to glimpse with the naked eye.

Finally, as we approach December, stunning Taurus and mighty Orion come into view for us to feast our eyes on, heralding the start of winter’s observing and the joys it promises.

What are your favourite autumn and winter astronomy targets? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com