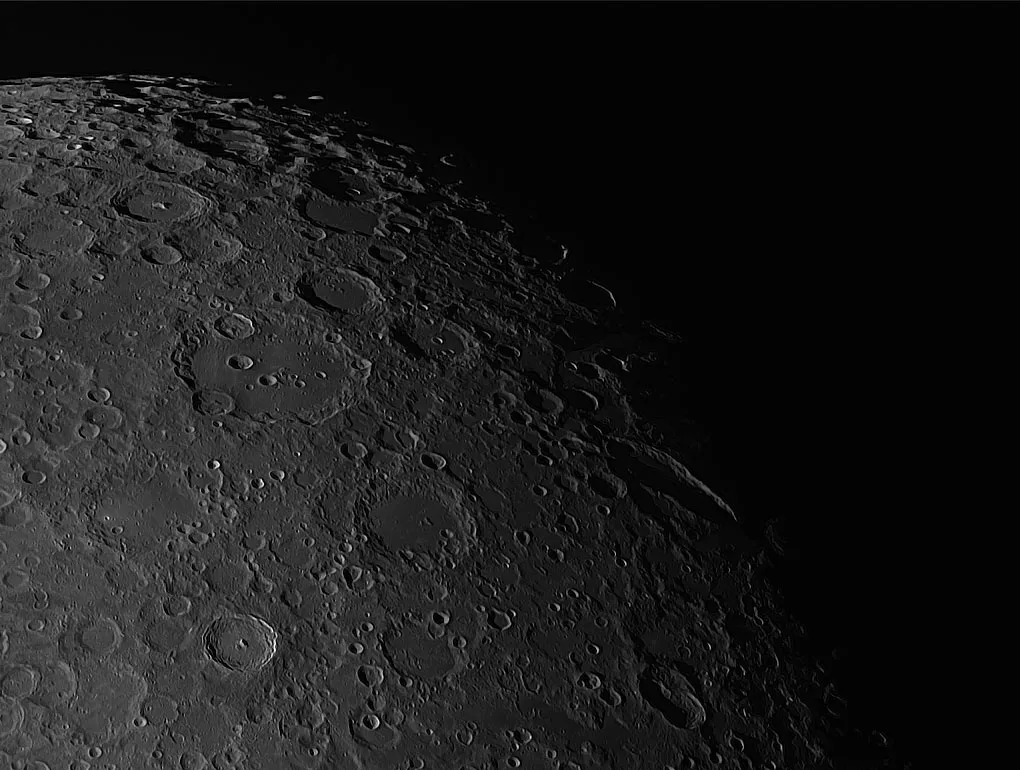

Located deep in the southern lunar highlands, few craters on the Moon are as majestically commanding as mighty Clavius. It’s a familiar feature on the Moon because of its size, characteristic appearance and because it’s prominently on view between the first and last quarter phases.

The start of this phase period is popular because it represents a time when viewing can be done at a relatively civilised time in the evening.

It would also make a good target for photographing. For more on this, read our guide on how to photograph the Moon.

Crater Clavius is massive, with a diameter of 225km. For comparison, this makes its diameter roughly equivalent to the straight line distance between Cardiff and Manchester.

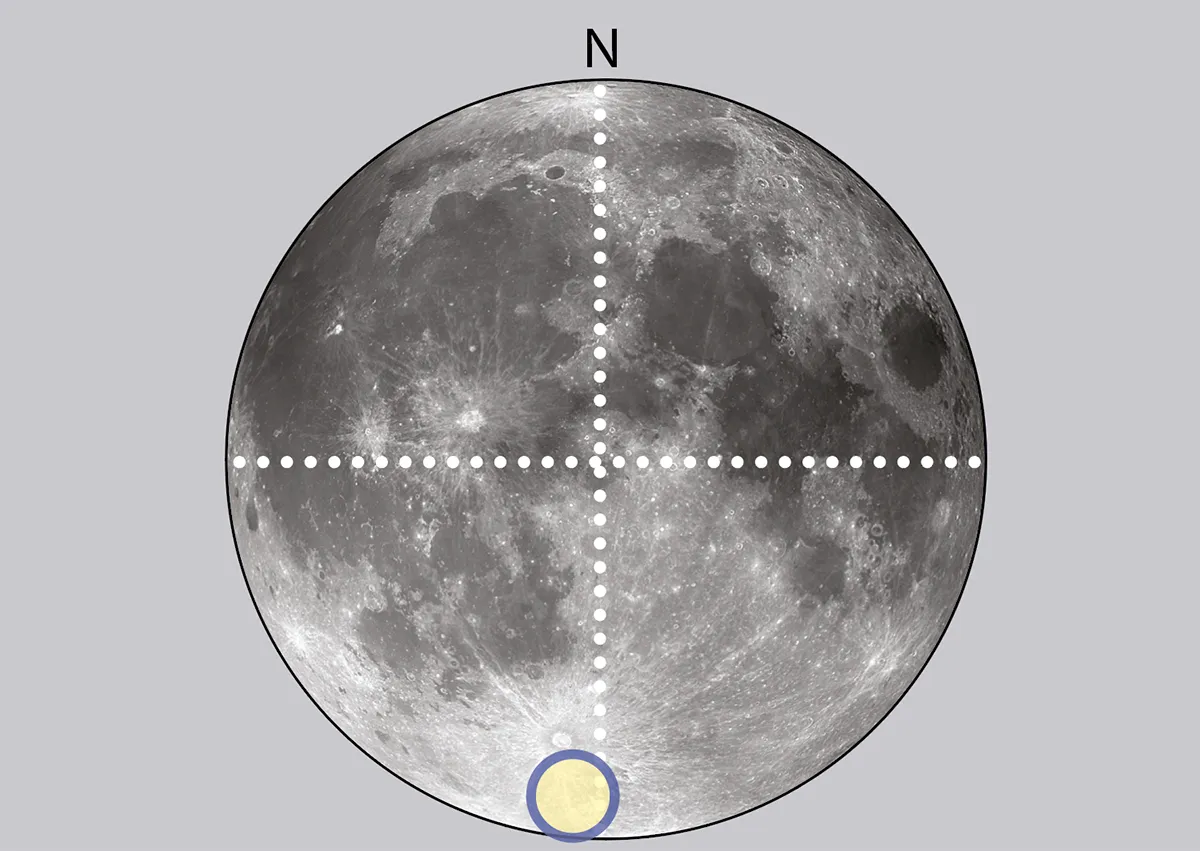

From Earth, Clavius has an elliptical appearance, which is a direct result of its southerly lunar latitude. The elliptical shape is due to an effect called foreshortening. If we were able to hover directly over it, Clavius would look more-or-less circular.

For more on lunar observing, read our complete guide to lunar maria, how to see Earthshineand the science behind a supermoon.

Facts about crater Clavius

- Size 225km

- Longitude/latitude 14.7˚ W, 58.6˚ S

- Age 3.9 billion years

- Best time to see One day after first quarter and last quarter

- Minimum equipment10x binoculars

What does Clavius look like?

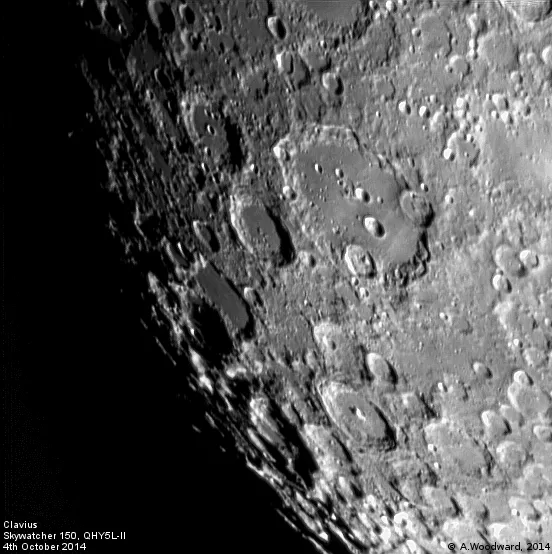

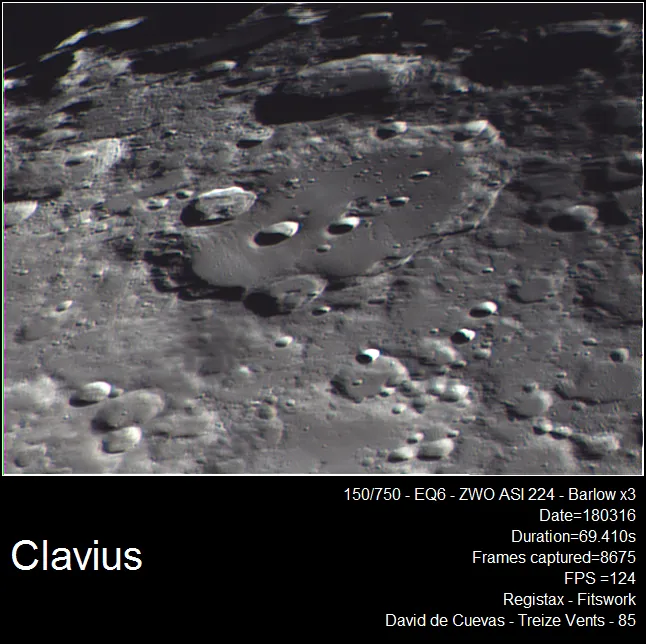

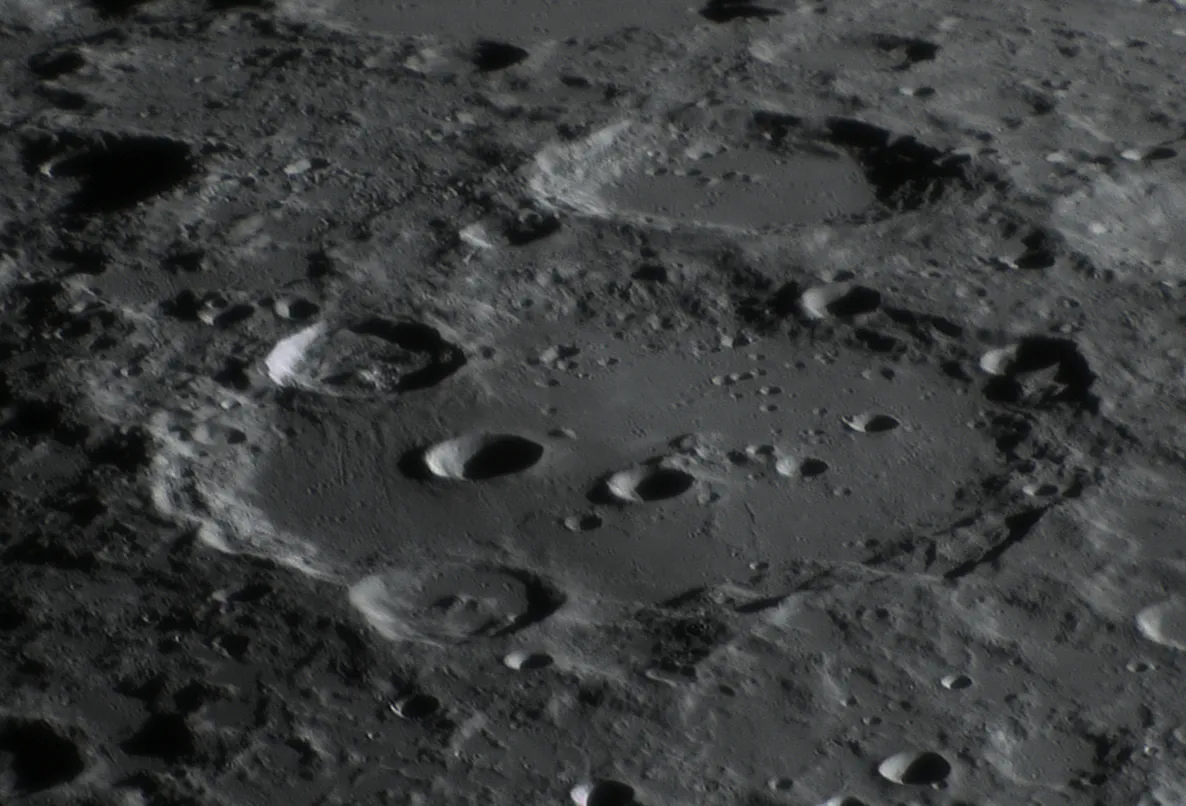

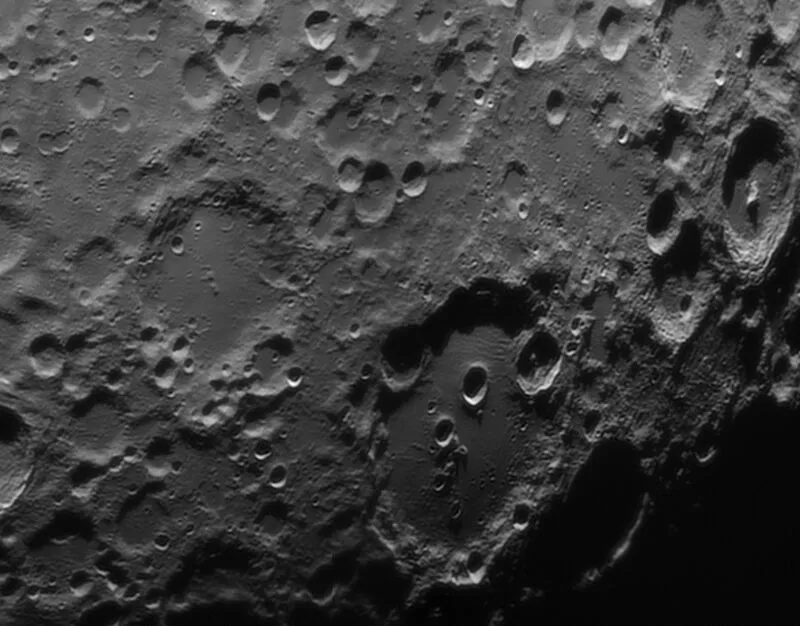

For such an old feature in such a heavily cratered part of the Moon, Clavius holds its appearance well.

Its rim edges are rugged but well-defined all the way round. One possible relaxation to this may be seen just to the west of 53km Porter, which rudely interrupts Clavius’s rim along the northeastern section.

The rim-line just to the west of Porter, appears to have been smoothed out. This is due to the extremely battered 44km crater Clavius M, almost completely disguised, sitting immediately next to Porter.

Head directly south of Porter to the southeast section of Clavius’s rim and here you’ll find another interruption caused by 55km Rutherfurd.

It’s interesting to compare the appearance of Porter and Rutherfurd. Although they are similar in size, Rutherfurd’s floor is rugged and cracked, while Porter’s is smooth with a neatly placed central mountain complex.

Rutherfurd also has a central mountain, but it’s displaced towards the northeast. An interesting pattern of ejecta ‘furrows’ appears to pass north and northwest of Rutherfurd.

Clavius's diameter is roughly equivalent to a straight line between Cardiff and Manchester

These, the offset mountain, and the fact that Rutherfurd’s actual shape (if foreshortening was removed) is elongated north to south, suggests the crater was formed by a low angle impact from the south or southeast.

Rutherfurd marks the starting point of an impressive arc of ever decreasing craterlets.

Immediately north of Rutherfurd is 28km Clavius D an easy target for a small telescope.

Continue northwest to 21km Clavius C. A small scope shouldn’t have any problems here either.

Continue west to 13km Clavius N, which requires at least 100mm of aperture to see clearly.

To the southwest of N is 12km Clavius J, again a good target for a 100mm scope.

If you want to test your telescope’s resolving power, head back to Clavius N and look north to a point just inside Clavius’s rim. Here lies 6km Clavius W, a size which starts to strain the limit of a 100mm scope.

Approximately one-quarter of the way from Clavius N towards W, offset slightly west, is 4km Clavius O which requires a 200mm instrument to see.

There are many more lumps and bumps to see on Clavius’s floor, and it’s an interesting exercise to see how many of those annotated in our main image can be spotted visually.

Have you managed to observe or even photograph Clavius? Let us know! Get in touch by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com or via Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

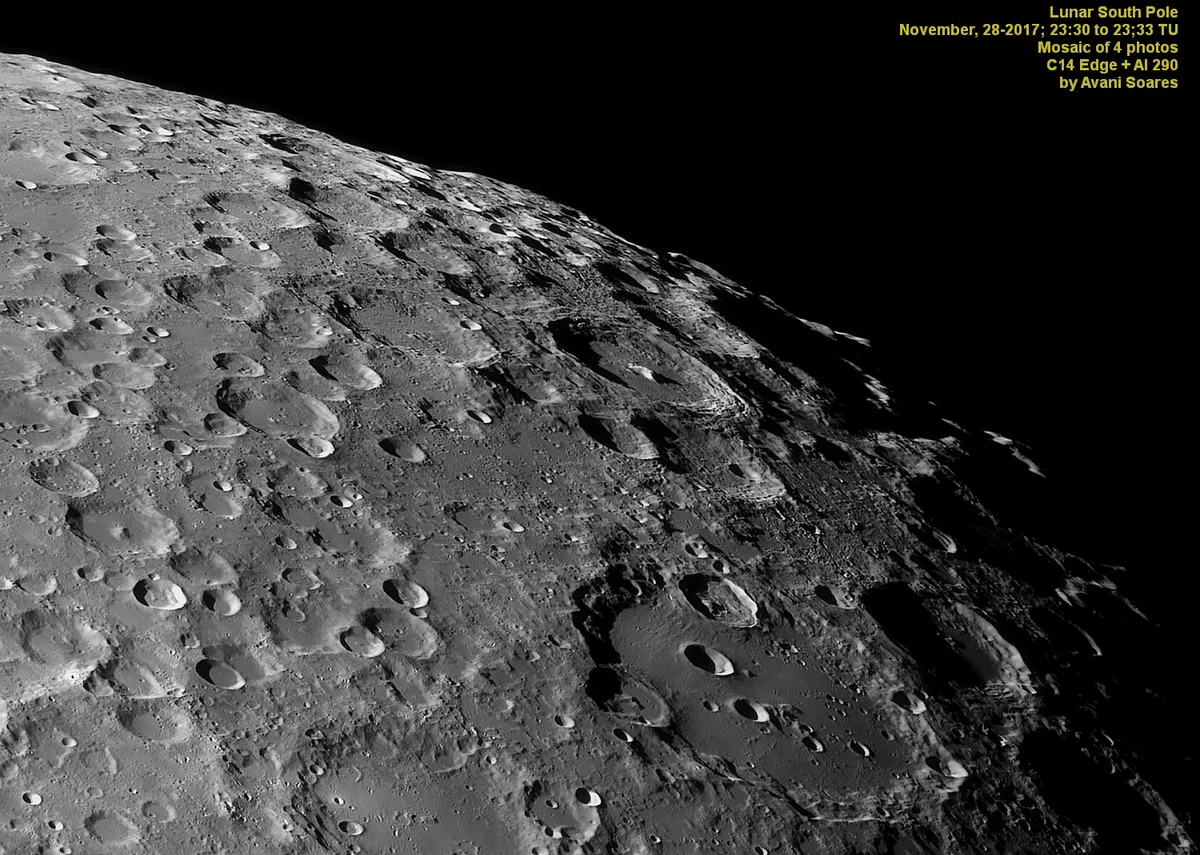

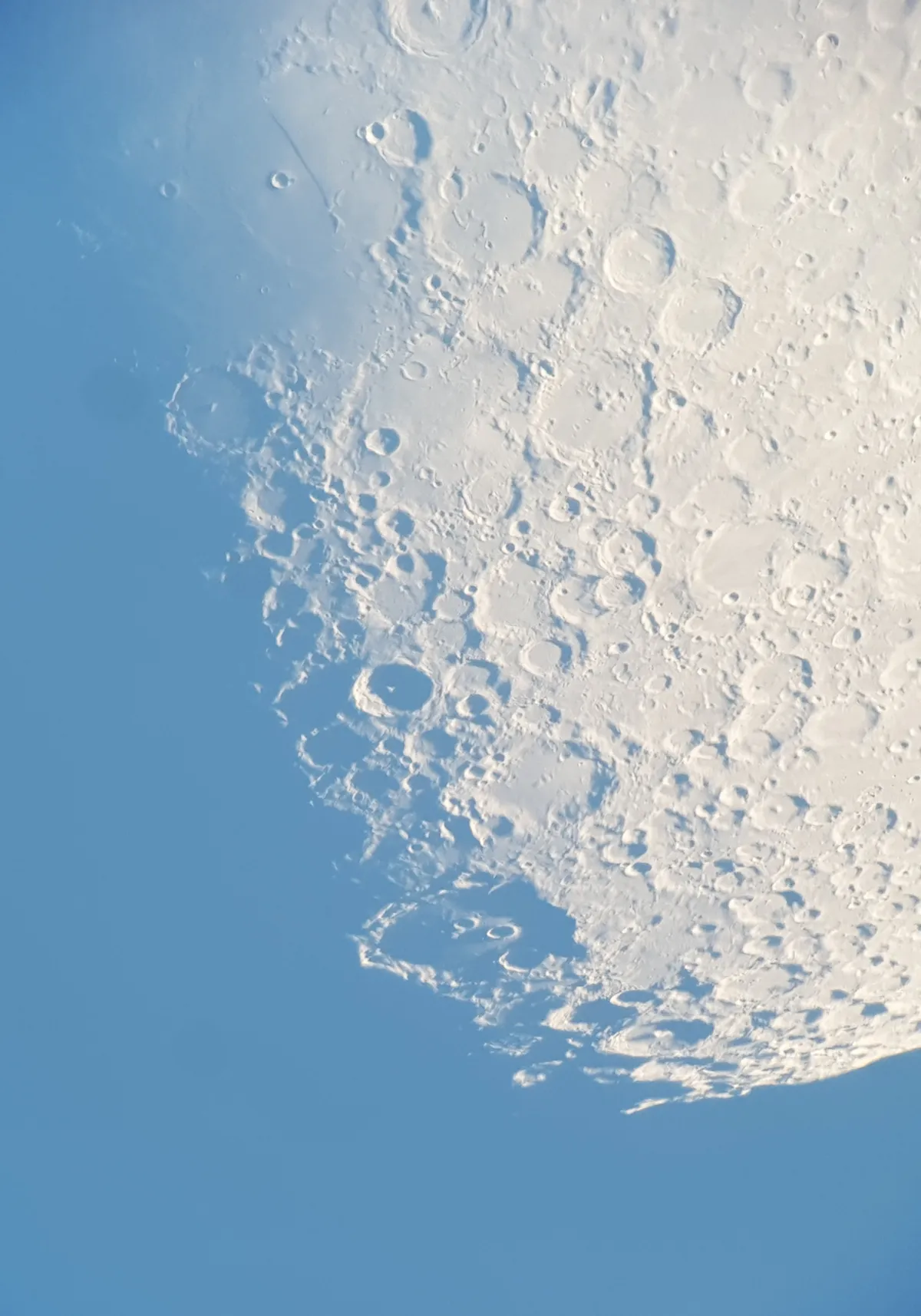

Images of Crater Clavius

A selection of astrophotos of the famous lunar crater captured by astrophotographers and BBC Sky at Night Magazine readers.