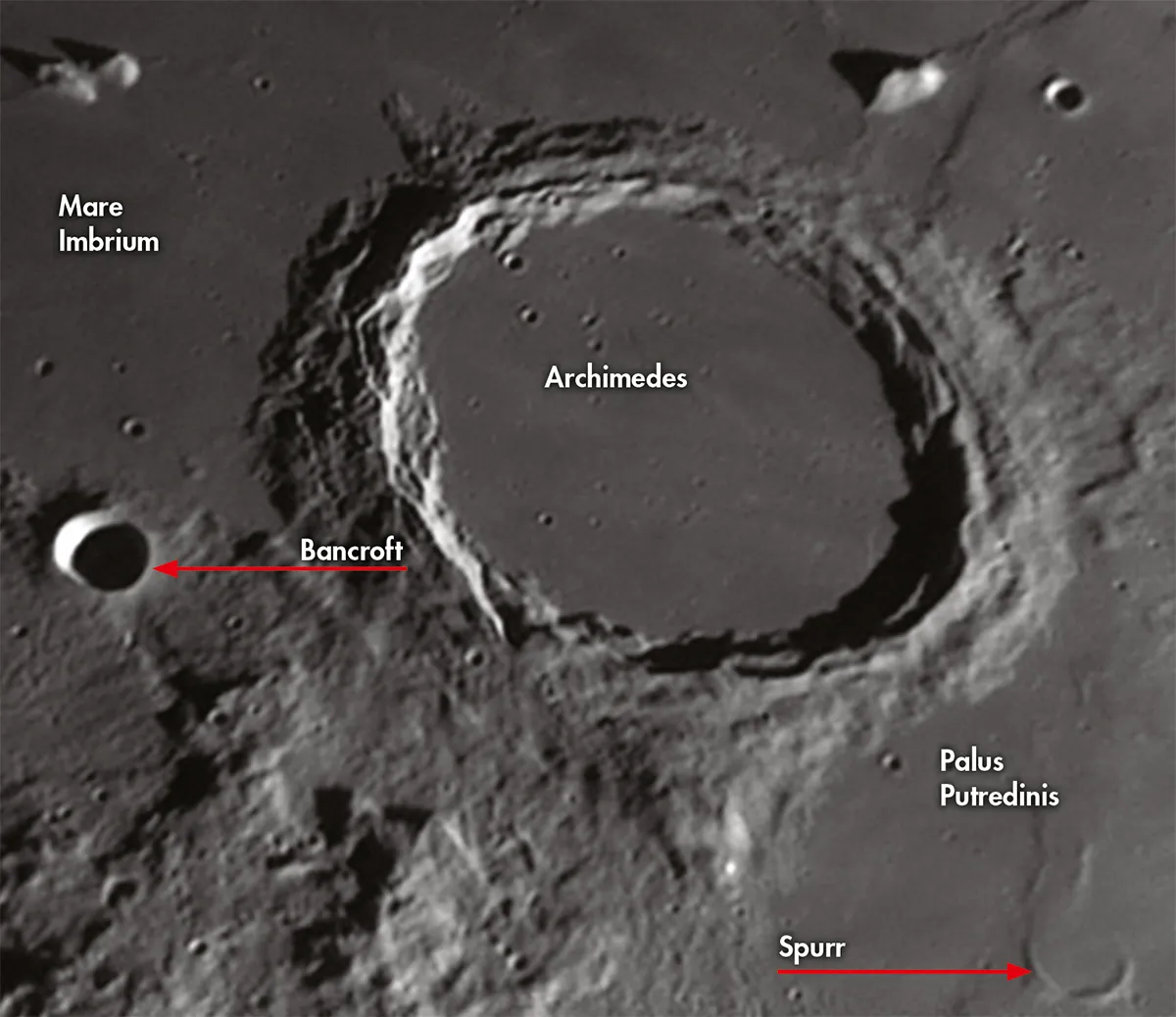

Archimedes crater is the largest formation on the Mare Imbrium. It comes into view soon after first quarter Moon, and is easy to identify whenever it is sunlit.

It is clearly shown on the map drawn by Thomas Harriot in 1609, well before Galileo made his first telescopic observations.

It is the senior of a trio of prominent formations in this part of the mare; the other two are Aristillus and Autolycus. You cannot possibly fail to be impressed by them.

For more info on lunar observing, read our guides on how to observe the Moon and the best features on the Moon.

Facts about Archimedes crater

- Size: 83km

- Age: Between 3.1 and 3.85 billion years

- Location: Latitude 29.7ºN, longitude 4ºW

- Recommended observing equipment: 4- to 6-inch telescope

Archimedes was named by Giovanni Riccioli in 1651, after the great Greek scientist who lived from about 287 to 212 BC.

The crater – ‘walled plain’ would be a better description – belongs to what is known as the Imbrian period, which extended from 3.1 to 3.85 billion years ago, and it is of course an impact structure.

The walls are continuous, rising to only a modest height above the outer terrain, but just over 2km above the sunken floor.

The floor itself was flooded with ancient lava, and is devoid of any prominent features.

Like Plato crater, in the Alps at the edge of the mare, it shows no trace of any central peak, but unlike Plato its floor is light-coloured, not dark grey.

The walls are terraced, and its shape is almost perfectly circular, though as seen from Earth it is foreshortened into an ellipse.

When I first saw a photograph of it taken from an orbiting spacecraft, I was impressed by its regularity.

Using the Lowell refractor at Flagstaff in Arizona, I have made careful searches for interior detail, but have never been able to make out more than light streaks and a few tiny, shallow pits.

This must be one of the smoothest areas anywhere on the Moon.

The other members of the trio are smaller, and Aristillus has a wonderful triple-peaked central structure.

North of Archimedes, beyond the well-marked Spitzbergen Mountains, the mare is smooth.

Between Archimedes and Autolycus the area has become known as the Sinus Lunicus, and contains two distinct craterlets: C has a diameter of 8km and D with a diameter of 5km.

On 14 September 1959 the Soviet spacecraft Luna 2 came down here. We’re not sure about its precise impact point, because it crash-landed and sent back no signal after arrival, but it was a notable achievement and the Russians can certainly claim to have been ‘first on the Moon’.

Perhaps the wreckage will be found one day. More than a decade later, on 30 July 1971, the Apollo 15 astronauts landed in the foothills of the Apennines, 200km southeast of Archimedes.

Just southeast of Archimedes in the Palus Putredinis (the Marsh of Decay) lies the 11km satellite crater Spurr, which is almost submerged; only its southern half protrudes significantly, though the northern half is traceable.

It was known as Archimedes K before being renamed in honour of Josiah Edward Spurr (1870-1950), an American geologist who wrote a classic book in support of the theory that the lunar craters are volcanic.

I was a strong advocate of this theory until the evidence against it became overwhelming! Bancroft, formerly Archimedes A, is a bowl-shaped, 13km crater to the southwest.

This whole area is one of the most photogenic on the Moon. Take an image including the Archimedes trio together with the southern end of the Apennines, and I guarantee that you will be pleased with the result.