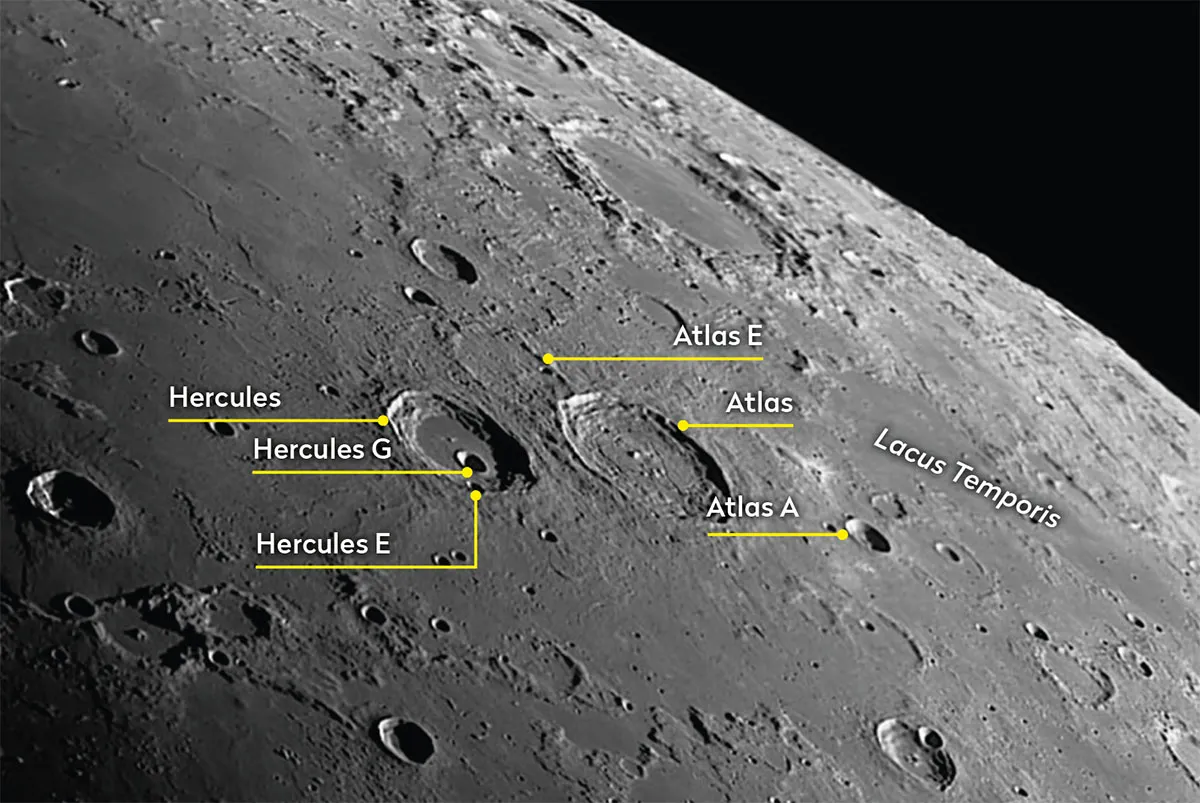

Crater Atlas is a distinctive feature of the Moon’s northeast quadrant. Located next door to 70km Hercules, it makes a contrast to its neighbour through a telescope because of their marked differences.

In this guide we'll take a look at both craters, revealing what you can see in this fascinating region of the lunar surface.

For more info on lunar observing, read our guides on how to observe the Moon and the best features on the Moon.

Facts about Atlas crater

- Diameter: 88km

- Longitude/latitude: 44.4º E, 46.7º N

- Age: 3.2–3.8 billion years

- Best time to see: Four days after new Moon (10 & 11 March) and three days after full Moon (23, 24 & 25 March)

- Minimum observing equipment: 2-inch refractor

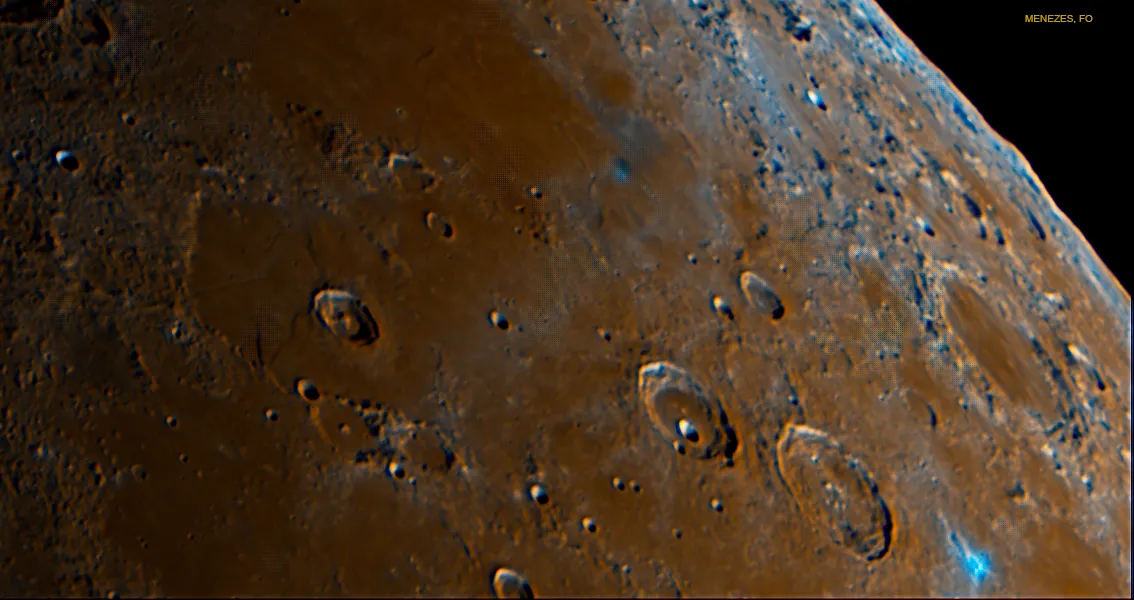

Atlas is circular in shape and bounded by an intricately terraced rim wall. The crater is 2km deep and has a complex floor covered in hills and cracks.

A lot of its anguished appearance is believed to have come from volcanism. The delicate series of cracks that crisscross its floor are known as Rimae Atlas.

Two dark patches referred to as Atlas North and Atlas South are very obvious when the crater is lit from overhead.

These are pyroclastic patches, the result of ‘fire fountains’ spouting molten material from below the crater’s floor.

The rest of the floor is relatively light in appearance. The rilles that form Rimae Atlas almost appear to spread, like a branching river, north from pyroclastic Atlas South.

Further evidence of volcanism can be seen from several dark, haloed craters spread across Atlas’s floor – these are craters surrounded by smaller pyroclastic flow.

There are few craterlets visible on Atlas’s floor through amateur telescopes, the most obvious being a 4.4km example near the northern rim.

Hercules Crater

After looking at Atlas, it’s quite amazing how different nearby Hercules appears. Rim to rim, Hercules lies just 30km to the west of Atlas.

This is another circular crater which, like Atlas, appears to us as an ellipse as a result of foreshortening.

Hercules also has a terraced rim but unlike the cracked floor inside Atlas, the floor of Hercules appears absolutely smooth apart from a few rounded hills.

There’s a notable intruder to Hercules’s floor in the form of 13km Hercules G. This sits squarely within the southern half of Hercules but, despite its size, doesn’t cause much other disruption.

The southwest rim is interrupted by 9km Hercules E. Hercules is younger than Atlas at somewhere between 1.1 and 3.2 billion years.

Located north of Atlas and east of Hercules is the 58km ghost crater, Atlas E.

The rim of this feature is very badly eroded and best seen when the lighting is oblique.

It’s most prominent to the east and north, but hardly resembles what you’d describe as a classic crater.

Atlas appears to overlap the southern rim of Atlas E, so Atlas E is obviously older than Atlas.

A particularly lovely, albeit small feature can be seen 85km to the east of the southern edge of Atlas’s rim. Here you’ll find a tiny 2.5km ray crater.

This is obviously a relatively young impact because its rays are bright and well defined, fanning out in delicate streaks mostly towards the east.

A couple of rays can be seen creeping over the boundary edge of Lacus Temporis, the Lake of Time. To the south of this unnamed ray crater is bowl-shaped 22km Atlas A.