A crescent Moon is one of the most spectacular sights to see in the night sky. Not only does it look beautiful, but a closer view through binoculars or a telescope will reveal the shadows of craters and other features like lunar maria, emphasised by the terminator (the line dividing the lit and unlit portions of the Moon).

The whole lunar cycle lasts around 29 days, and during that time it passes through several stages known as the phases of the Moon.

Read our guide on how to photograph a thin crescent Moon

During a lunar month, the Moon goes from new Moon, through the waxing crescent phase up to first quarter when the Moon's disc appears half illuminated.

As more of the Moon is illuminated by the Sun over time, this is known as the waxing gibbous phase, which occurs until full Moon, when the lunar disc is fully illuminated.

Then, the cycle reverses and goes from full Moon, through a waning gibbous phase until last quarter when, again, the lunar disc is half-illuminated (but this time on the opposite side).

Slowly, less and less of the Moon's disc is illuminated during the waning crescent phase, until we're back to new Moon and the cycle begins again.

The waxing crescent phase lasts from about day 1 to day 6 of the lunar cycle, and the waning crescent phase lasts from about day 23 to day 29.

Observing the crescent Moon

These crescent phases make for a great time during which to get a good look at our lunar neighbour.

If you can manage to observe the Moon every night - weather permitting - you'll notice the terminator creeping across the lunar disc as more - or less - of the Moon is illuminated by the Sun.

Below we'll reveal what you can see on the Moon during its crescent phase, and specific features or lunar phenomena to look out for.

For more advice on exploring the wonders of the Moon - whatever its phase - read our guide on how to observe the Moon and the best features on the Moon.

If you want to capture the Moon's beauty, read our guides on how to photograph the Moon and how to draw the Moon.

Observing a waxing crescent

Day 3: Earthshine

A thin crescent Moon is a beautiful sight hanging in the west after sunset. But does the dark portion seem to be gently glowing? Binoculars or a small telescope will confirm that it is.

This ghostly illumination comes from sunlight reflected off Earth and is appropriately known as Earthshine. This sight is often called: “the new Moon in the old Moon’s arms.”

The dominant feature of the sunlit crescent is a mare – a large, dark plain on the Moon’s surface – called Mare Crisium.

Due to the very slow rolling motion of the Moon, known as lunar libration, Mare Crisium sometimes appears almost at the edge (the lunar limb), while at other times it’s slightly farther in.

Regardless of its position you can explore the mare’s western shore for low, sinuous ridges (‘wrinkle ridges’) and small craters called ‘craterlets’.

These include Picard, which is just 23km (14 miles) across. Just north, along the terminator, is the larger 126km (79 mile) Cleomedes. You might be able to spot the central peak inside it.

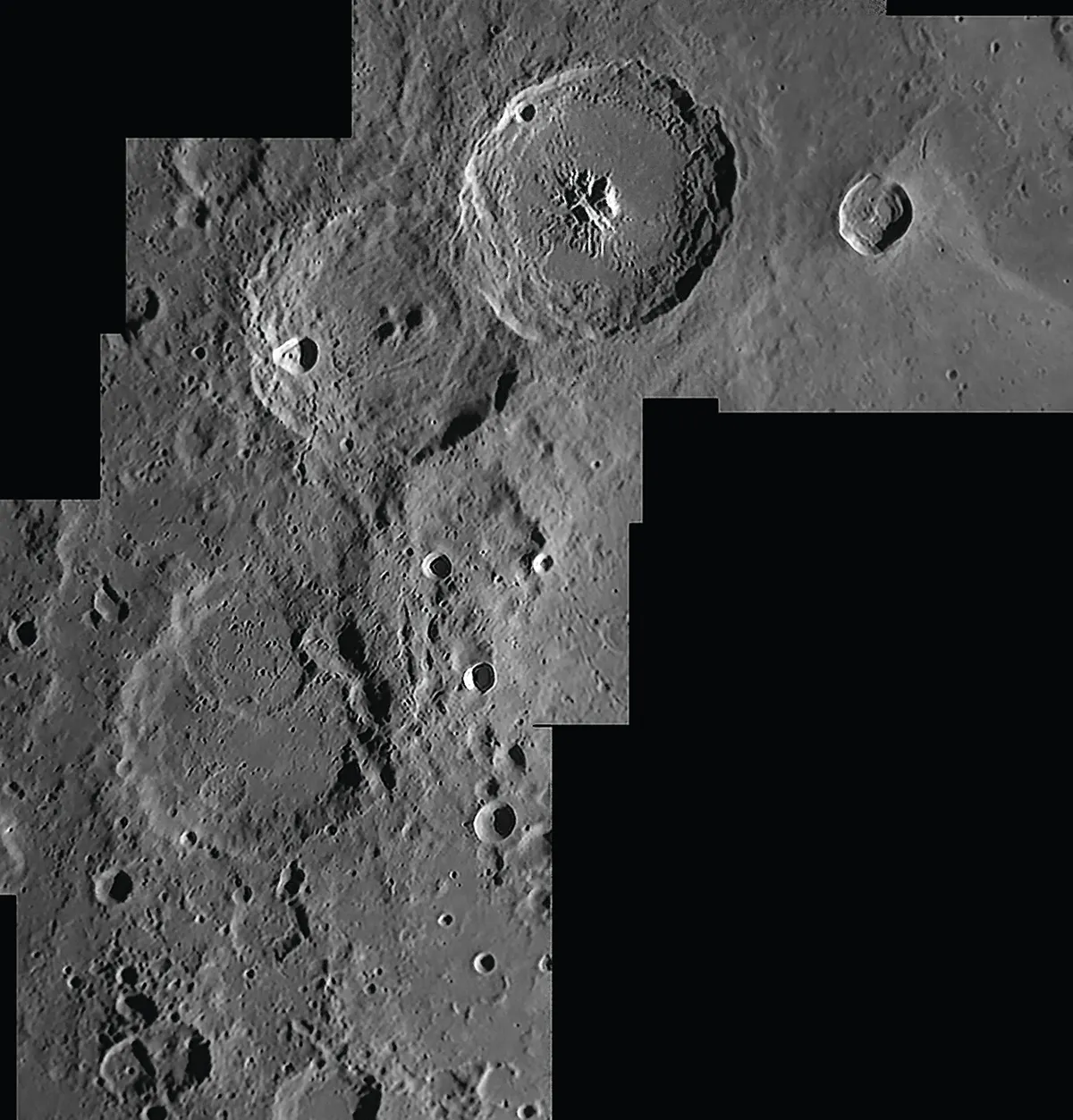

Day 5: Craters Theophilus, Cyrillus and Catharina

Several great trios of craters are visible on the Moon, and tonight you can explore one of them.

On the terminator, just below the middle of the Moon, is the magnificent chain of Theophilus, Cyrillus and Catharina – their ages increase as you follow them from north to south.

All are 100km (62 miles) across and they’re easy to find, lying just west of another large lunar mare – Mare Nectaris.

Theophilus, with its terraced walls and central peak, is the most spectacular of the three. Its southwestern rim covers neighbouring Cyrillus.

Explore the overlap, and look for a small crater inside Cyrillus’s western wall. Below Cyrillus is Catharina.

The oldest of the three craters, it has disintegrated walls and smaller craters superimposed on it.

Observing a waning crescent

Day 24: Sinus Iridum

Perched on the northwestern edge of Mare Imbrium is Sinus Iridum, which in Latin means ‘Bay of Rainbows’. Sinus Iridum is actually a 236km (148 mile) crater, but it was flooded with lava after the impact that created it.

Standing out in sharp relief around Sinus Iridum are four craters some 40km (25 mile) across. Bianchini is dug into Iridum’s northern wall, and Sharp and Mairan lie to the west.

Above Sinus Iridum, embedded in another mare (Mare Frigoris), is the fourth crater – Harpalus.

You should also take the time to explore the Jura Mountains, which shape the northern half of Iridum.

Then return to Mare Humorum in the southwest of the Moon. Below it, to the southeast, is a very elongated crater called Schiller.

About 180km long by 70km wide (113 by 44 miles), Schiller’s appearance could be the result of a low-angle impact.

Day 26: Schickard, Wargentin and Phocylides

This is a challenging phase to observe because the Moon is usually low and large features aren’t easy to locate.

Near the centre of the Moon’s edge (limb) is the 172km (108 mile) basin Grimaldi, which has a dark floor due to the lava that’s flowed across it in the past. You can see it with binoculars.

To the east is the vast Oceanus Procellarum (‘Ocean of Storms’ in Latin) – at 2,500km across it’s the Moon’s biggest mare. On its western side is a white swirly patch called Reiner Gamma.

It’s unusual because it has a magnetic field all of its own. In the southwest, numerous craters including Schickard, Wargentin and Phocylides appear elongated because of the curvature of the Moon – an effect known as ‘foreshortening’.

Send us your best images of a crescent Moon by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com