Gassendi crater is particularly easy to recognise and is of special interest. It is named after the French astronomer Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655), who corresponded with Galileo and was a strong supporter of the Copernican theory.

He was also the first to observe the transit of Mercury.

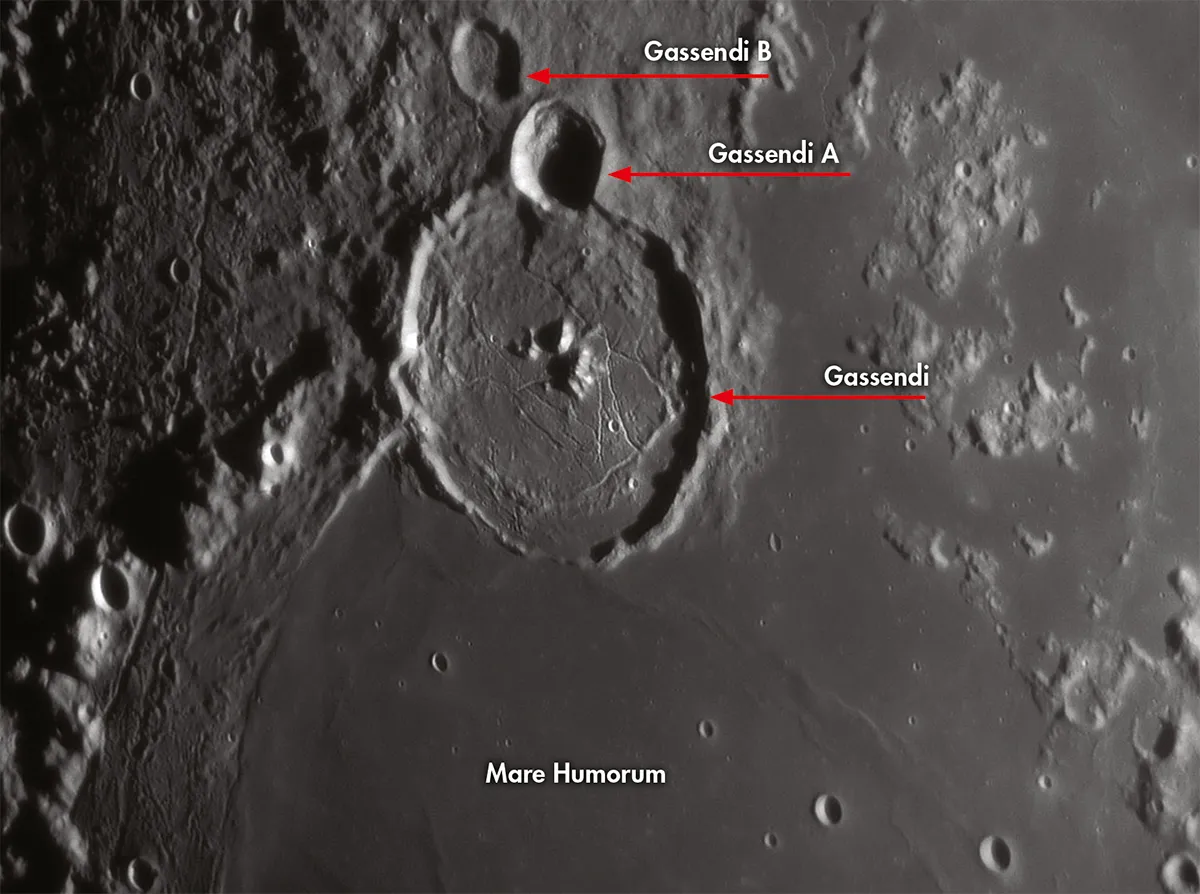

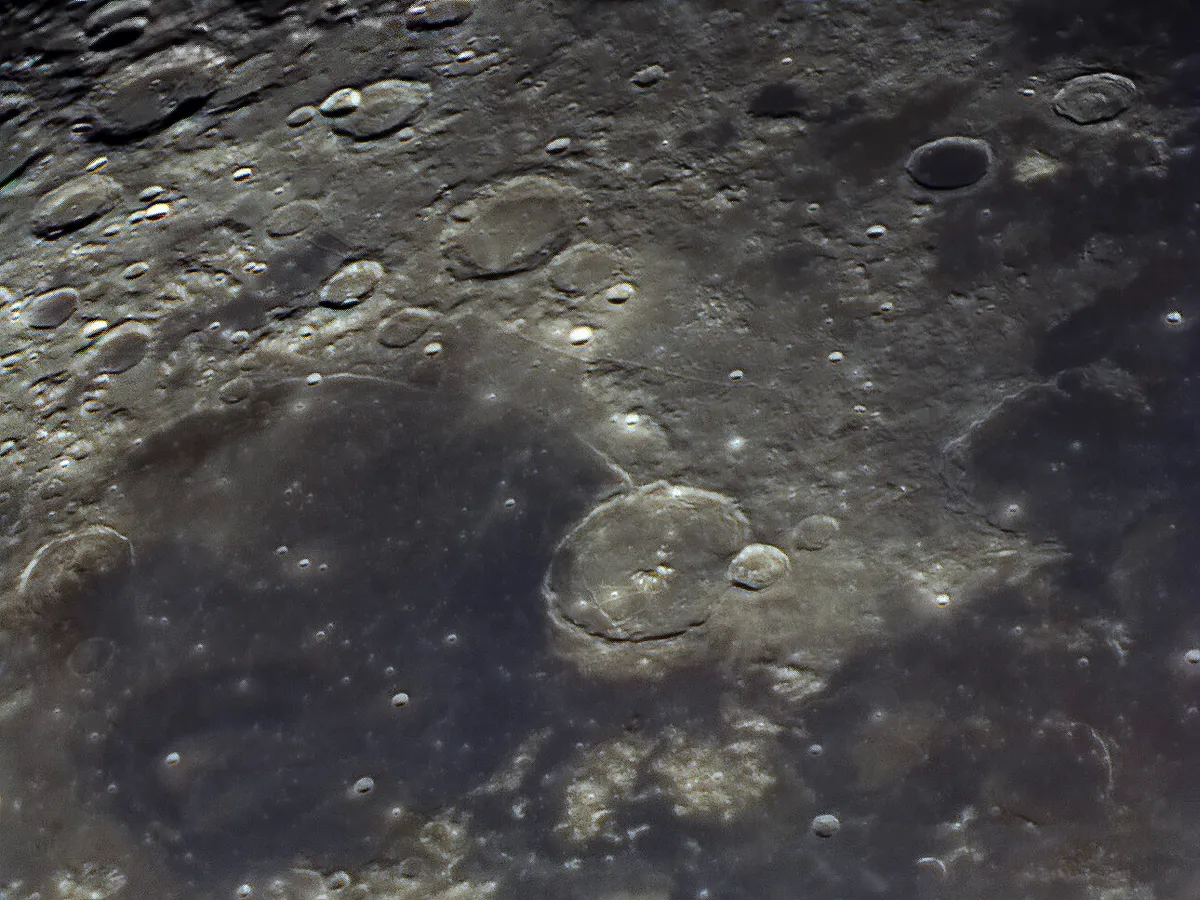

Gassendi lies at the northern edge of the Mare Humorum, so that it comes into view well before full Moon and remains visible until after last quarter Moon.

Facts about Gassendi Crater

- Size 114km

- Age Around 4 billion years

- Location Latitude 17.5°S, longitude 39.9°W

- Recommended observing equipment: 6-inch telescope

For more info on lunar observing, read our guides on how to observe the Moon and the best features on the Moon.

It is recognisable under any conditions of illumination, and is a favourite target for lunar photographers.

It was flooded during the formation of the mare, but although the wall shows evidence of erosion it remains complete, apart from the short section adjoining the 34km crater Gassendi A. Its age must be around four billion years.

The outline is circular and the crater lies well away from the limb so that thereare no marked foreshortening effects.

The floor is covered with solidified lava, and instead of one well-defined central mountain there are several obvious peaks spread around the middle of the floor. The loftiest of these isabout 1.2km high.

Even a small telescope will show hummocks and rough areas all over the interior, and in the southern part of the floor there is a ridge concentric with the outer rim.

This rampart itself isn’t particularly high or steep, but there are a few peaks rising well over a mile above the deepest part of the floor.

The most notable feature of the interior of Gassendi is its system of rilles. They crisscross the floor, and are very easy to see when observing conditions are even moderately favourable.

Few other craters have rill systems of such complexity.

There have been a number of reports of transient lunar phenomena (TLP) in and near Gassendi.

Minor and infrequent though they are, it is now generally agreed that they do occur, particularly in regions rich in rilles (craters Aristarchus and Alphonsus for example).

One event in Gassendi, on 30 April 1966, was seen by several observers at several different sites; with my 15-inch reflector I recorded it as a wedge-shaped, reddish orange streak extending from the inner wall to the peaks near the centre of the floor.

TLP-hunting is fascinating, but success is very occasional, and you must be careful about effects due to the Earth’s atmosphere.

It is only too easy to be deceived, and many reports, even in the official TLP catalogues, must be regarded as spurious.

There are satellite craters around Gassendi, but only A and B are more than 16km in diameter.

Gassendi A is named ‘Clarkson’ on some maps, after the English amateur Roland LT Clarkson, but this is not in the official International Astronomical Union list. To the south there are only a few small craters.

It is fair to say that Gassendi is one of the most attractive of the Moon’s craters, and well deserves attention.

The aspect changes spectacularly with the changing solar illumination, and photographs taken on successive nights will be most rewarding.