One of the most important and striking craters on the Moon, Copernicus is found in the Oceanus Procellarum, slightly northwest of centre.

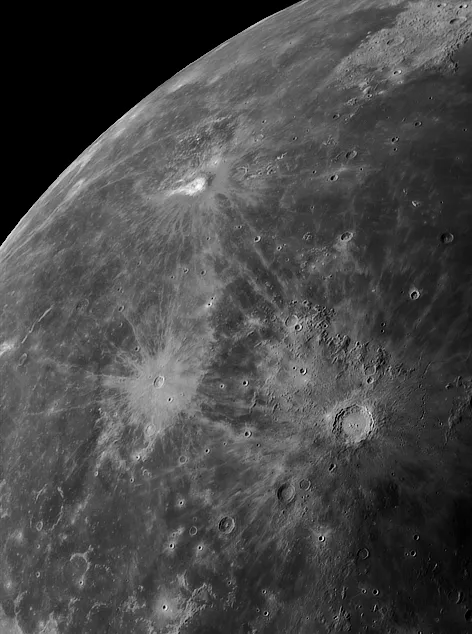

It is easy to identify whenever it is sunlit, and it is at the heart of one of the two main ray-centres.

Crater Tycho, in the southern uplands, is the other. Under high lighting, the Tycho and Copernicus rays are so dominant that they make other features difficult to locate.

Facts about Copernicus Crater

- Size: 90km

- Age: Less than a billion years

- Location: Latitude 9.7ºN, longitude 20ºW

- Recommended observing equipment: 4-inch telescope

Copernicus Crater is named after the great Polish scholar who showed that Earth orbits the Sun, rather than being the centre of the Universe – but there is a story here, not without its amusing side.

The main craters were named in 1651 by astronomer Giovanni Riccioli, who drew the first really useful telescopic map of the Moon.

Not unnaturally he named prominent features after himself and his pupil Grimaldi, but he was no supporter of Copernicus, and continued to believe the old Ptolemaic geocentric theory of a stationary, motionless Earth.

To show his contempt, he "flung Copernicus into the Ocean of Storms". His plan misfired; the crater he chose is magnificent, and is often referred to as ‘the Monarch of the Moon’.

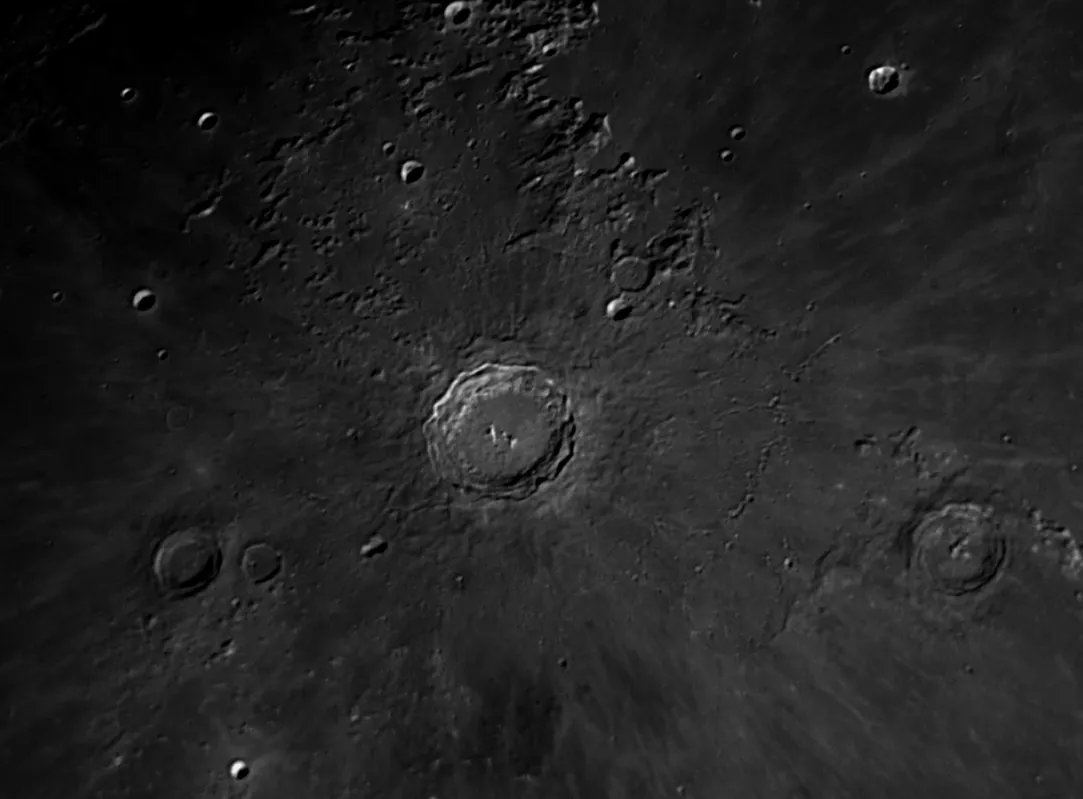

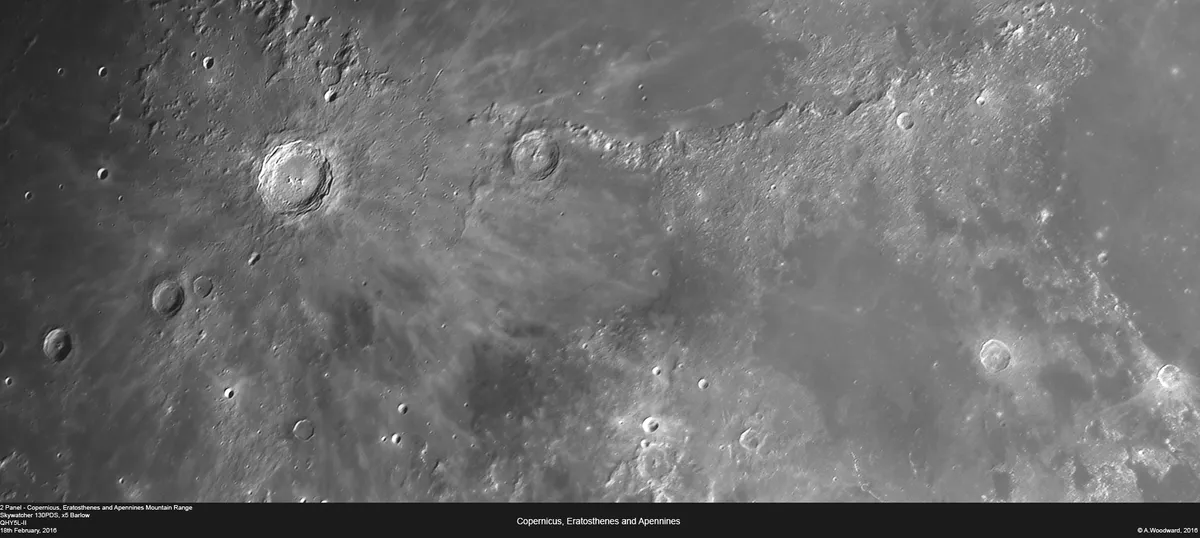

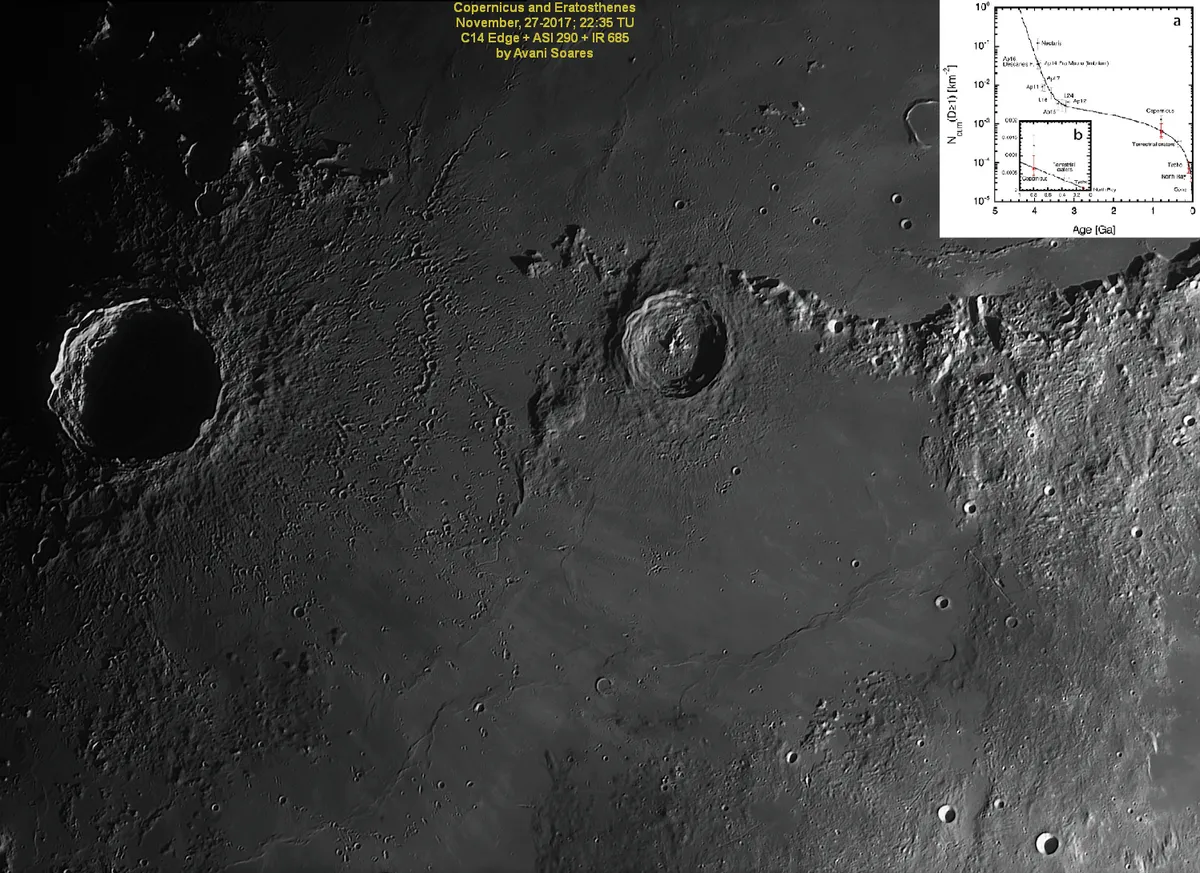

Because Copernicus is not far from the centre of the lunar disc it is not appreciably foreshortened, and is on view for a good part of every lunation.It is 90km in diameter with high, beautifully terraced walls.

There is no single central mountain, but there are several peaks and groups of hills near the middle of the floor, which is otherwise fairly level and has not been flooded with lava.

It is fascinating to watch the progress of sunrise or sunset over the crater and the surrounding area; the whole scene changes dramatically over a short period of time.

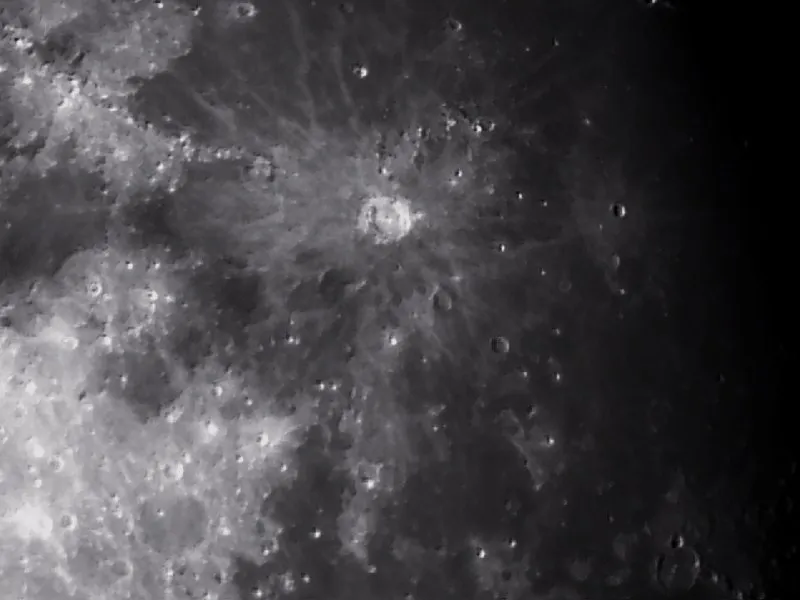

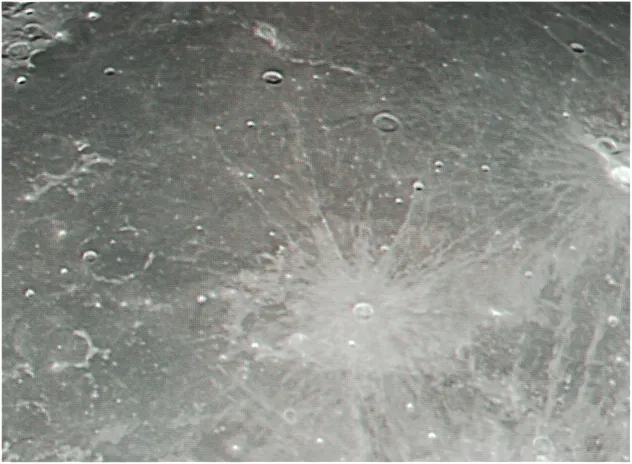

The rays extend for at least 805km, and overlap rays from other craters, notably Kepler, so they must be younger.

Copernicus post-dates the Late Heavy Bombardment, and may well be less than a billion years old.

The rays differ from those of Tycho, because its rays are long, linear and regularly arranged, while those from Copernicus are less regular and give the impression of being tangential to the crater.

There are small secondary craters, and the area is hilly.

Copernicus is bright because, on the lunar timescale, it is so young. It has not been darkened by the effects of the solar wind or micrometeorite bombardment.

The rays are surface deposits, and do not show up until the Sun is well above their horizon.

Well to the northeast of Copernicus, not far from the end of the Apennines, lies the 58km diameter crater Eratosthenes, which is very like a slightly smaller edition of Copernicus, apart from the fact that it has no comparable ray system.

Southwest of Eratosthenes we find crater Stadius, which must have once been a grand formation, but has been so overwhelmed by lava that it has been reduced to the status of a ghost.

The walls are traceable under suitable lighting conditions, but nowhere rise to more than a few tens of feet.

In 1966, when mapping the Moon from spacecraft had only just begun, an oblique view of Copernicus was shown in an image from NASA’s Lunar Orbiter 2.

It was widely acclaimed, and became known as ‘the Picture of the Century’. It is still well worth looking at, and it is easy to see why this crater deserves its nickname – the Monarch of the Moon.

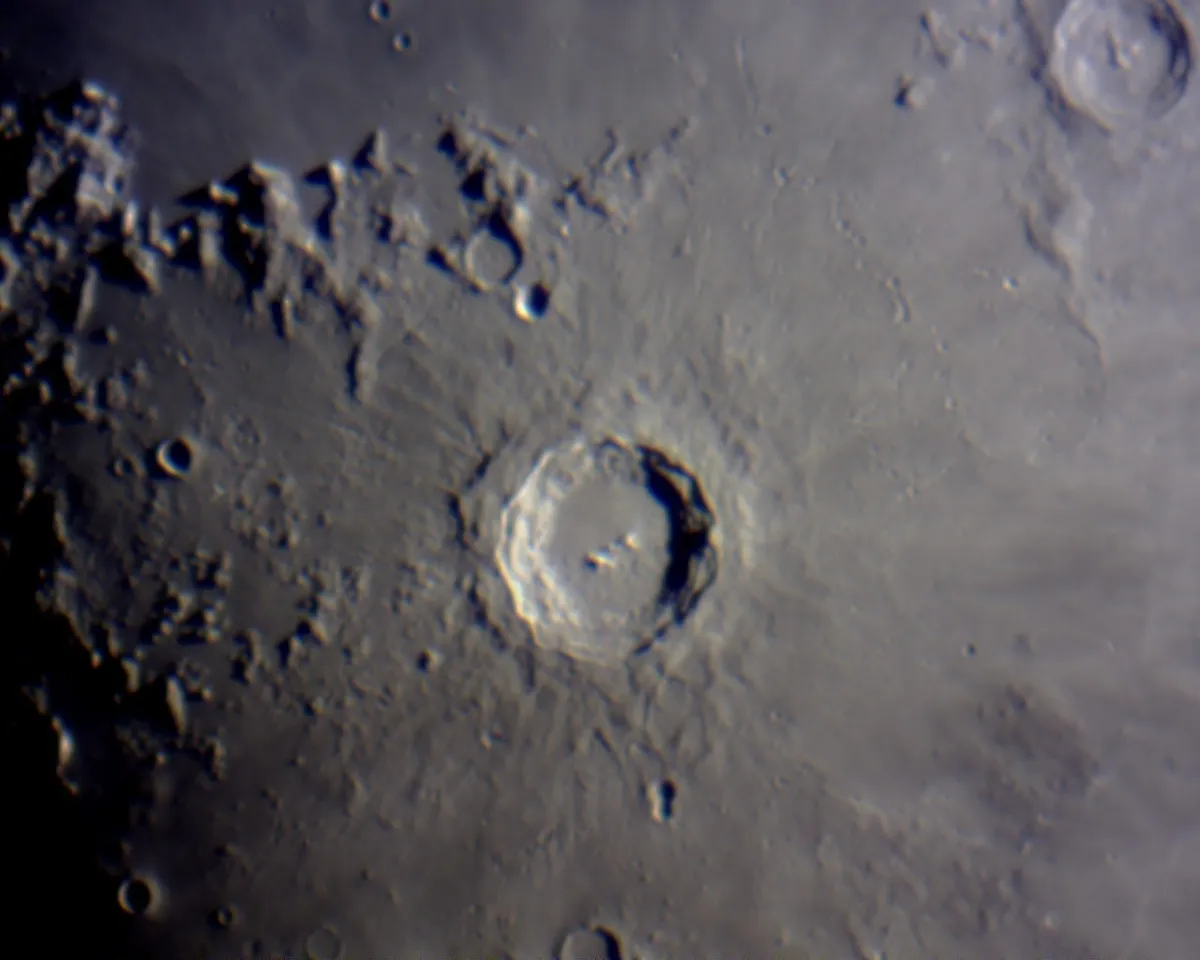

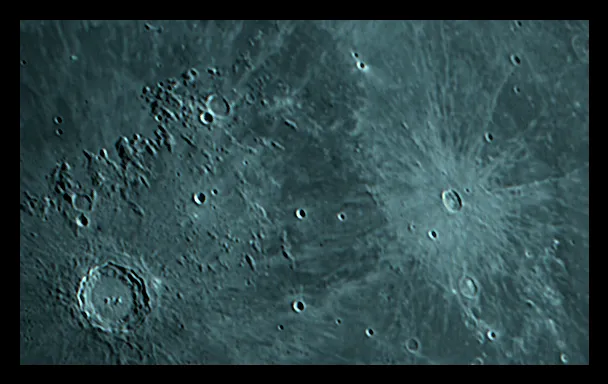

Below is a selection of images of Crater Copernicus captured by lunar astrophotographers and BBC Sky at Night Magazine readers.

For more info on how to make the most of our Moon, read our guide on how to observe the Moon or our pick of the best features to observe on the Moon.

Or try our tutorials on how to photograph the Moon and how to draw the Moon.

And don't forget to send us your images or share them with us via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.