Mare Crisium, or Sea of Crises, is one of the smaller lunar maria; its total area is no more than that of Great Britain.It is separate from the main system of maria, and is evident even with the naked eye.

Being close to the northeastern edge of the visible disc, it comes into view on a thin crescent Moon and remains prominent until soon after full Moon phase.

It is clearly shown on Thomas Harriot’s lunar map of 1609 (it is too often forgotten that Harriot was the first telescopic observer of the Moon, months before Galileo), and was named by Giovanni Riccioli in 1651.

It is of Pre-Imbrian age, formed some time between 3.8 and 4.6 billion years ago.

For more info on lunar observing, read our guides on how to observe the Moon and the best features on the Moon.

Facts about Mare Crisium

- Size: 450x560km

- Age: Between 3.8 and 4.6 billion years

- Location: Latitude 17.0°N, longitude 59°E

- Recommended observing equipment: 4-inch telescope

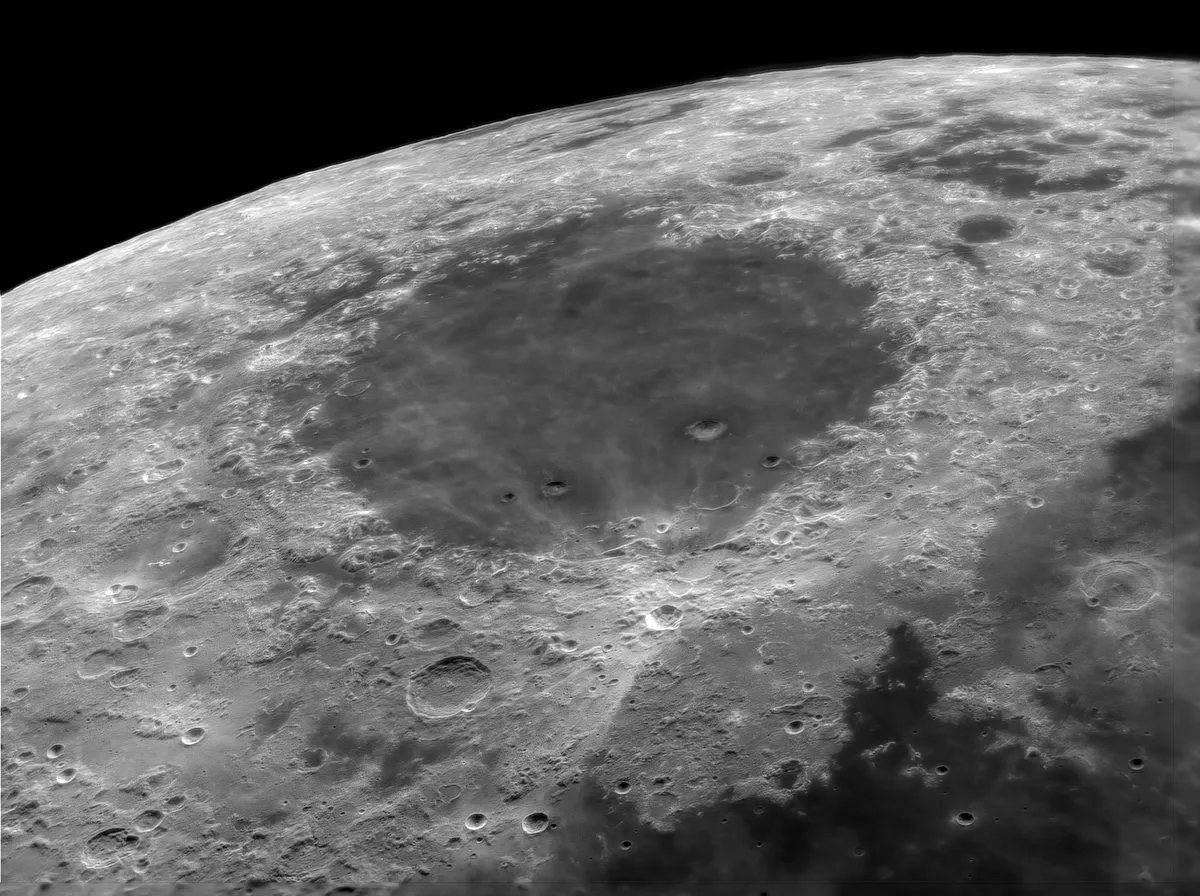

The mare appears to be elliptical in a north-south direction, but this is due to foreshortening; its diameter is 450km north-south, but 560km east-west.

Its outline is well-defined, though there are no high mountains along the borders as there are with, for example, the Mare Imbrium.

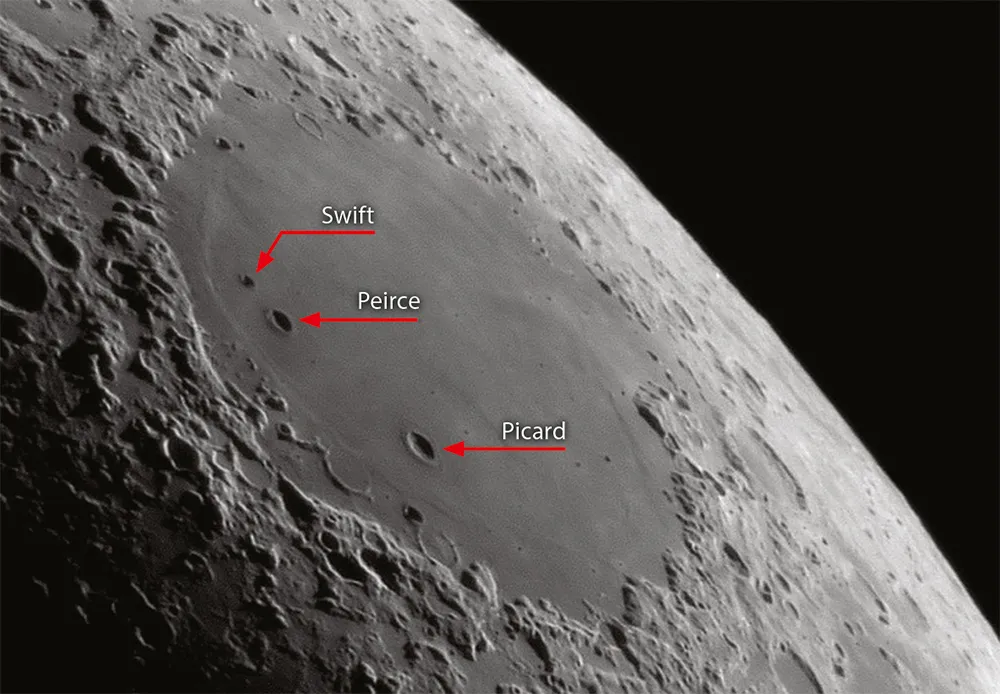

The basin is relatively flat, and darker than the surrounding areas. The three largest craters on the floor are of modest size: these are Picard (diameter 23km), Peirce (18km) and Swift (10km).

Here and there can be seen indications of ‘ghost’ craters that have been totally flooded, and there are also some craters only a few kilometres across.

Picard is a normal impact crater, with a maximum depth of about 2.5km. The walls are terraced, and in the centre of the floor there is a low hill – a useful test for small telescopes.

Peirce is bowl-shaped, with several interior ridges and hills.

To its north is Swift, which is circular and well-marked. It was originally named Peirce B, and then Graham until given its present name by the International Astronomical Union.

On the western edge of the mare, west of Picard, there are some interesting features.

Yerkes, 36km across, is a crater that has been so inundated by lava that the walls are discontinuous, and the colour and albedo of the floor are similar to the adjacent surface.

The Mare Crisium is crossed by obvious wrinkle ridges, several of which have been named (for example Tetyaev Dorsa and Harker Dorsa, in the western floor, both of which are over 150km long).

I have found that they remain visible under almost all conditions of solar illumination.

Jutting out into the mare from the east is Cape (Promontorium) Agarum. Just to the northwest are some tiny craterlets, connected by low ridges.

They seem to have been first noted around 1935 by the English amateur Robert Barker, and four of them make up what I have termed ‘Barker’s Quadrangle’.

I have found that they show puzzling changes in visibility, and several transient lunar phenomena have been reported here, though with no reliable confirmation. Perhaps the area is worth monitoring.

When you are looking at the Mare Crisium, seek out the isolated craterlet Eckert (17.3°N, 58.3°E) just to the east of a low wrinkle ridge.

Eckert is a mere 3km across, and can be elusive, but I always make a point of hunting for it whenever I am looking at this fascinating little sea – one of my favourite areas of the Moon.

Images of Mare Crisium

Below is a selection of more images of Mare Crisium captured by astrophotographers and BBC Sky at Night Magazine readers.

For astro imaging advice, read our guide on how to photograph the Moon. And don't forget to send us your images or share them with us via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.