The Lunar Apennines (Montes Apenninus) may not be the very highest mountains on the Moon, but they are certainly the most spectacular.

The range was named by Johannes Hevelius after our own Apennines – one of the few of Hevelius’s names to have survived the later revision by Giovanni Riccioli.

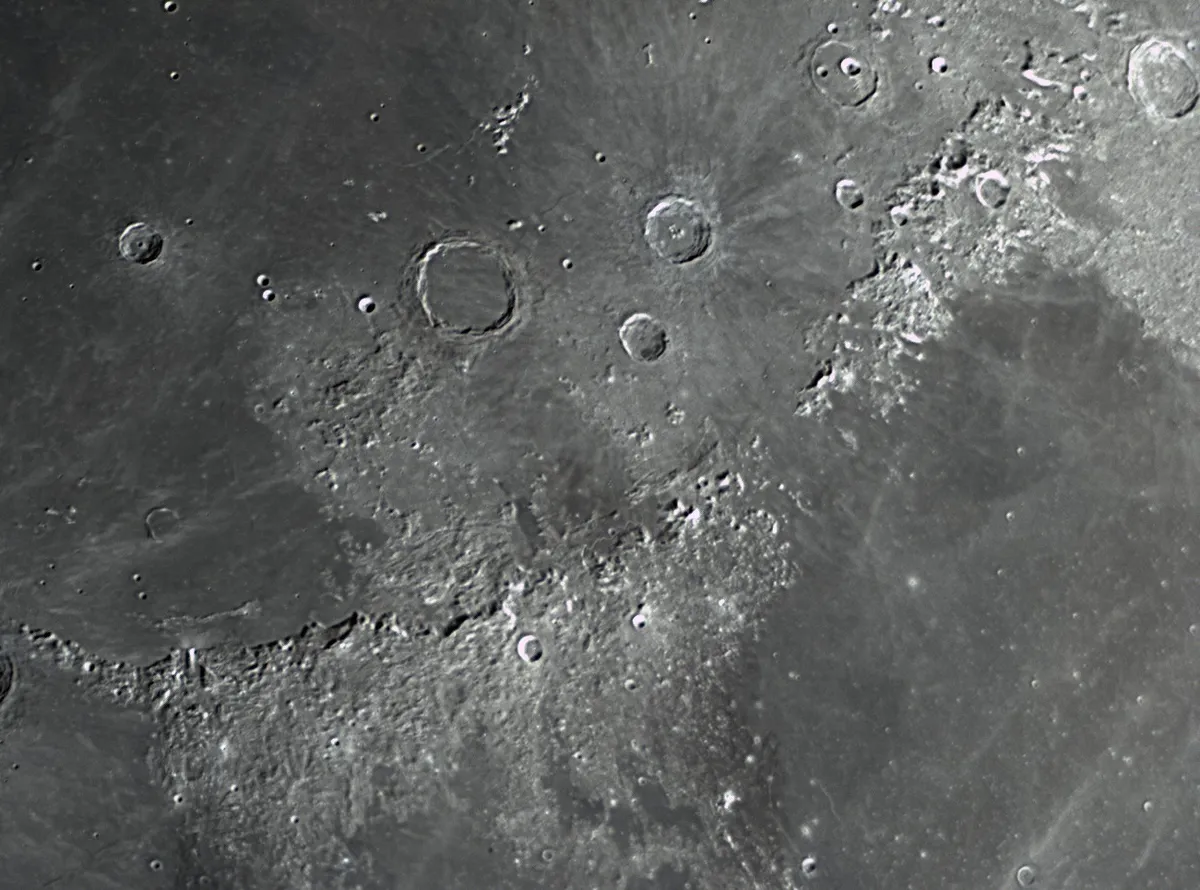

Montes Apenninus forms the southeastern border of the Mare Imbrium, the largest and most prominent of the regular lunar maria, and is dominant for much of each lunation.

The Apennines do not form a continuous border all round the Mare Imbrium, but probably once did, and what we call the ‘Imbrium Basin’ is everywhere traceable; the colossal impact that produced it had profound effects all over the Moon.

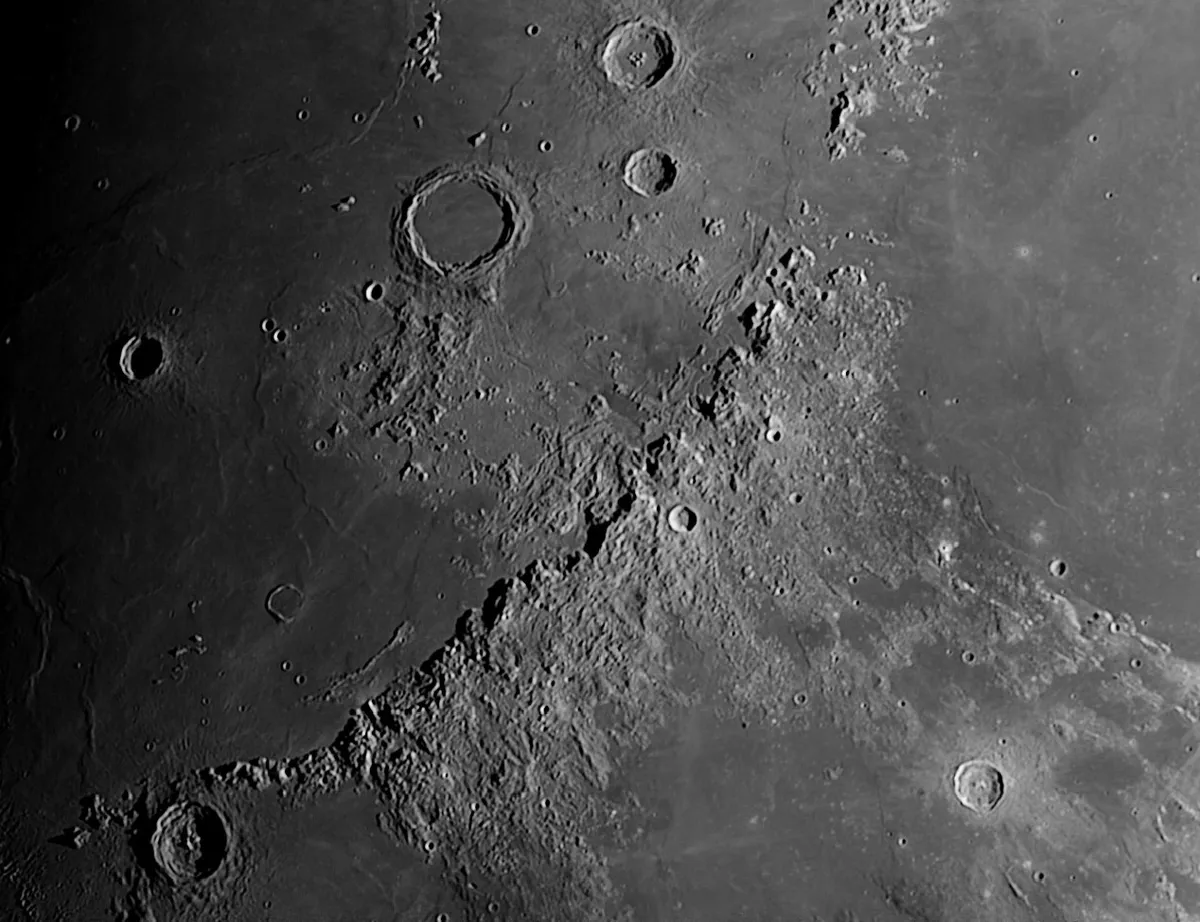

From close to Eratosthenes, one of the most splendid and best-preserved of all craters, it runs along the Mare Imbrium’s edge separating it from the smaller, darker-floored Mare Vaporum.

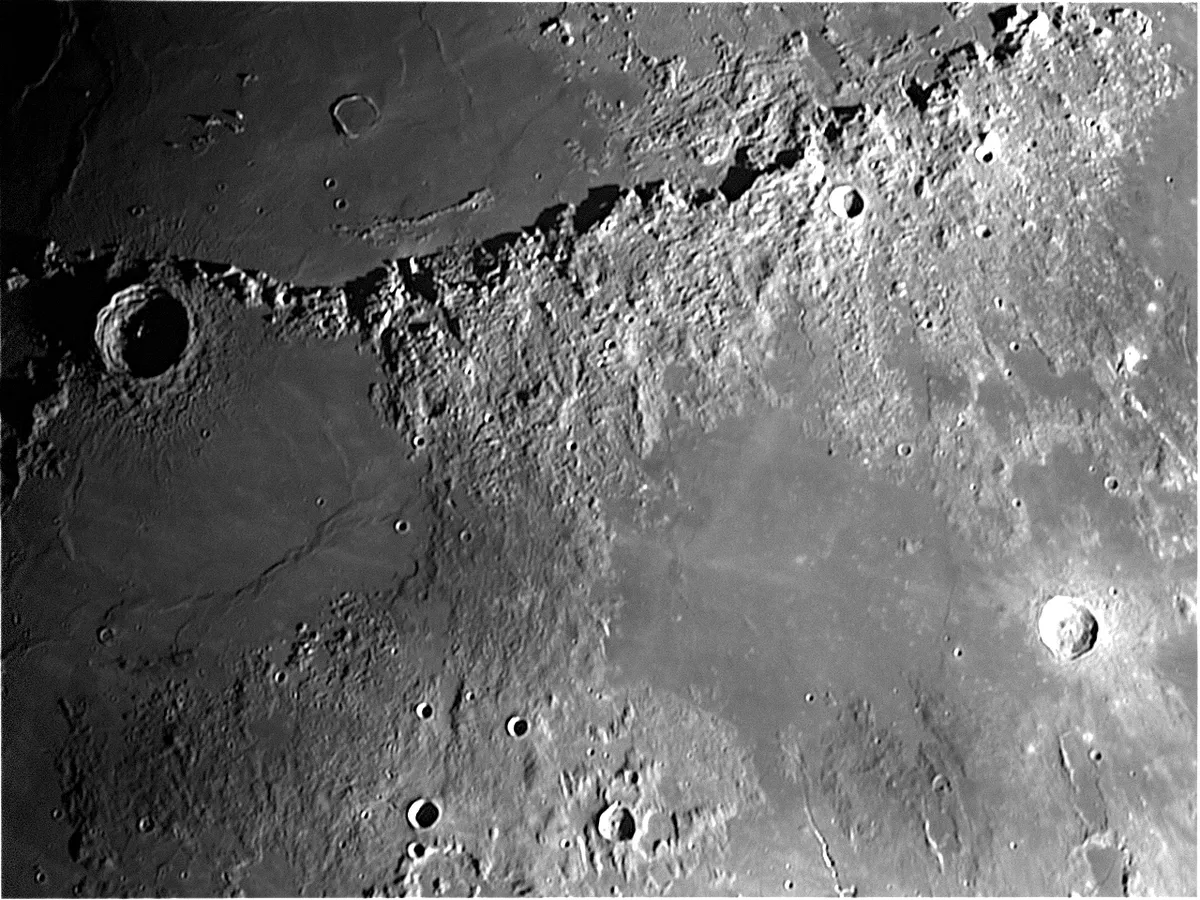

The scene is particularly striking around first quarter, when the peaks cast their long, sharp shadows across the plain. The highest peak in the Apennines, Mons Huygens, rises to about 6.1km.

Facts about Montes Apenninus

- Size600km long

- AgeBetween 3.2 and 3.85 billion years

- Location Latitude 18.9°N, longitude 3.7°W

- Recommended equipment for observing 4- to 6-inch telescope

To the north, the Mare Imbrium is bounded by the Montes Alpes, which do not join up with the Apennines. There is a gap between the two ranges, so that Imbrium’s floor is connected with that of the adjacent Mare Serenitatis – there is a difference in level and also in age.

The lunar Alps are by no means the equal of the Apennines, but they have special interest because they contain features not found elsewhere on the Moon. Of particular note is the huge Vallis Alpes, a colossal gash through the mountains.

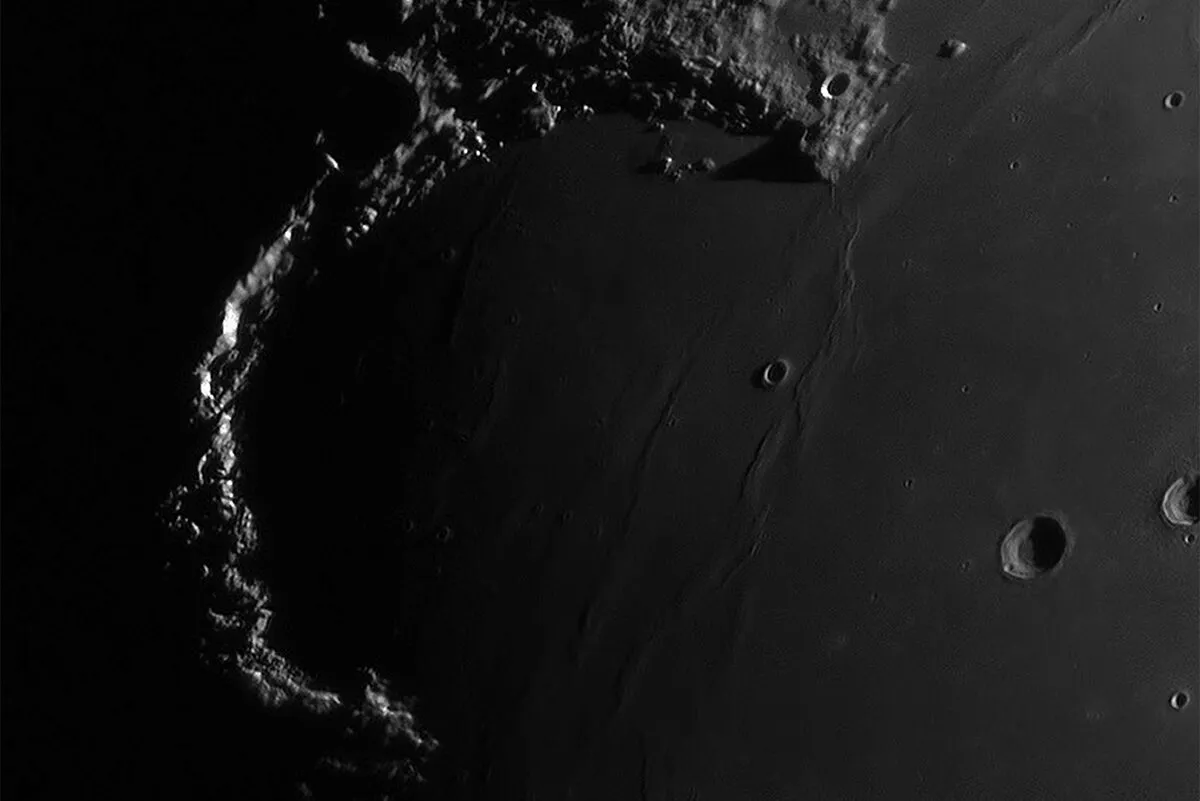

Last, but by no means least, is the Sinus Iridum, or Bay of Rainbows. It must once have been a major crater at the edge of the mare but the seaward wall has been flooded and is now barely traceable, so we are left with a large bay.

You can watch it as the Sun rises over it. Obviously, the Sun’s rays first catch the peaks on the far side, while the bay itself is left in darkness.

This is generally known as the ‘Jewelled Handle’ and, of course, occurs once in every lunation. It is a phenomenon known as a clair-obscur effect. For advice on how to see it, read our pick of the best clair-obscur effects to see on the Moon.

The mare does not contain many large craters, apart from the main three, of which the largest is the 80km Archimedes.

There can be no better known feature on the whole of the Moon than the Mare Imbrium. One can picture the scene when the huge meteoroid crashed down so long ago!

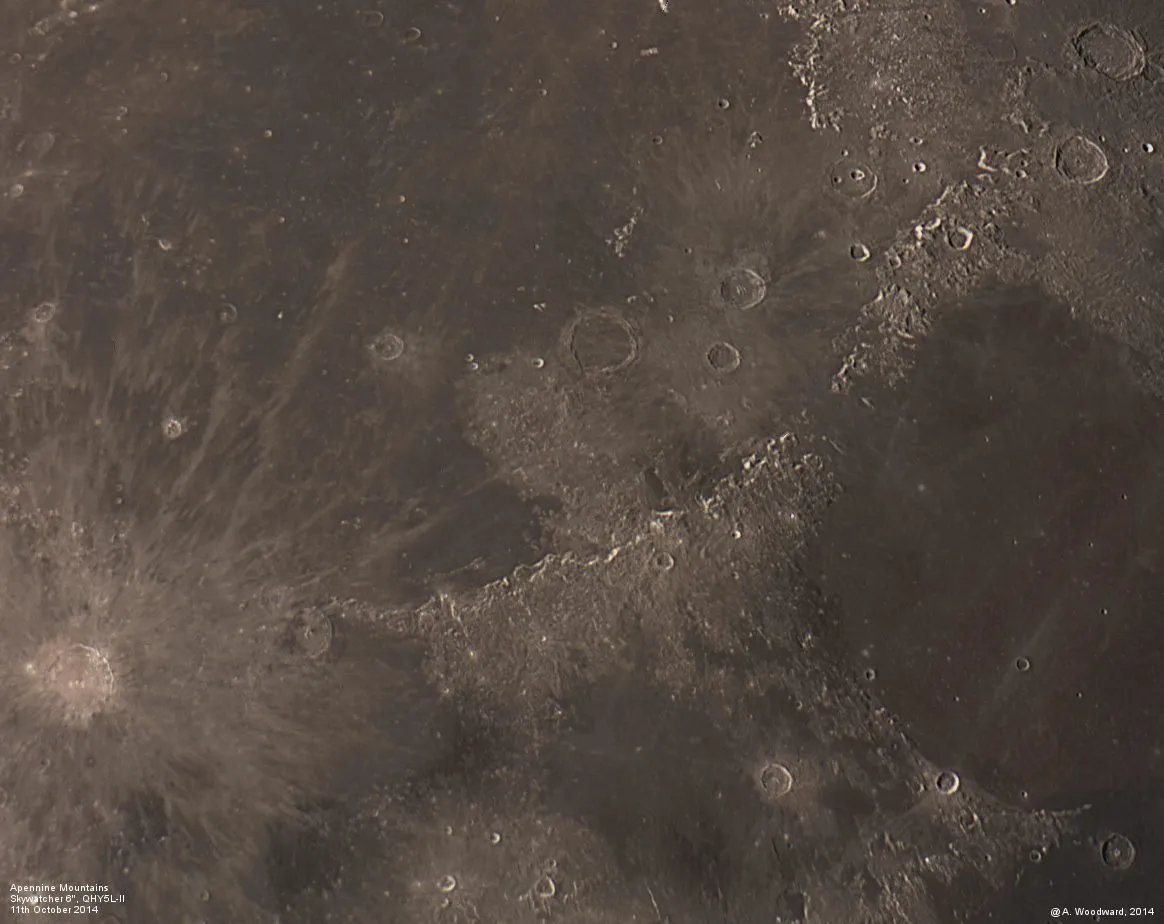

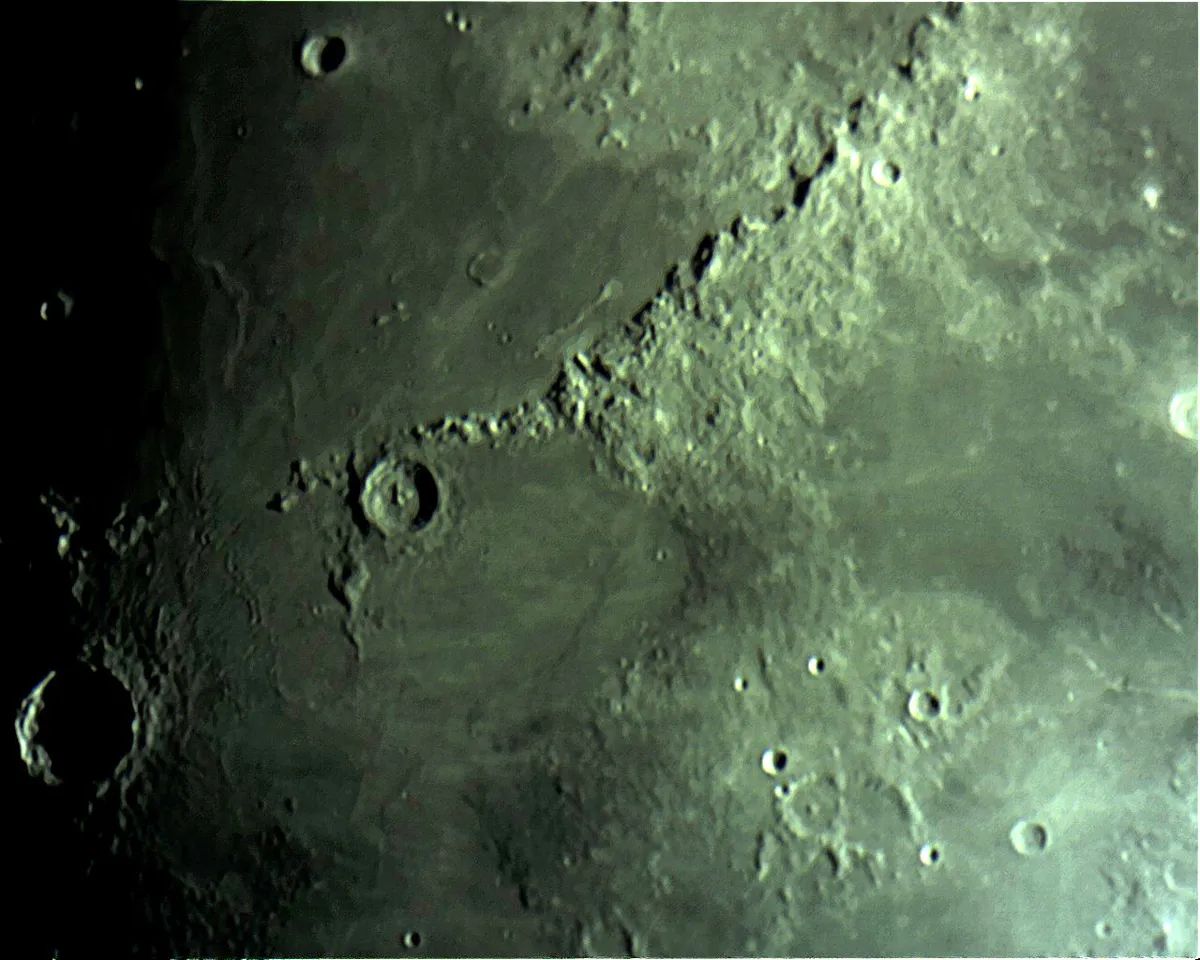

Below is a selection of images of Montes Apenninus captured by lunar astrophotographers and BBC Sky at Night Magazine readers.

For more advice on making the most of the Moon, read our guide on how to observe the Moon or our pick of the best features to observe on the Moon.

Or you could try your hand at lunar photography with our tutorial on how to photograph the Moon. If sketching is more your thing, read our guide on how to draw the Moon.

And don't forget to send us your images or share them with us via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.