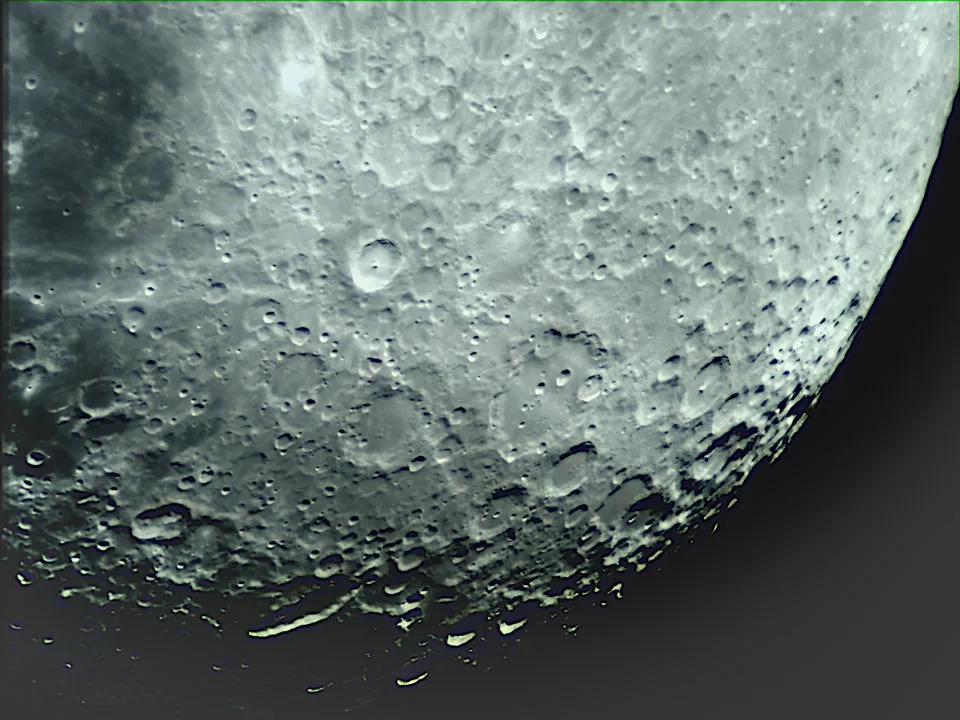

For part of each lunation, Tycho Crater is perhaps the most conspicuous feature on the entire Moon.

It is named after Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), the Danish astronomer whose measurements of the movements of Mars enabled Johannes Kepler to show that the planets’ orbits are elliptical, not circular.

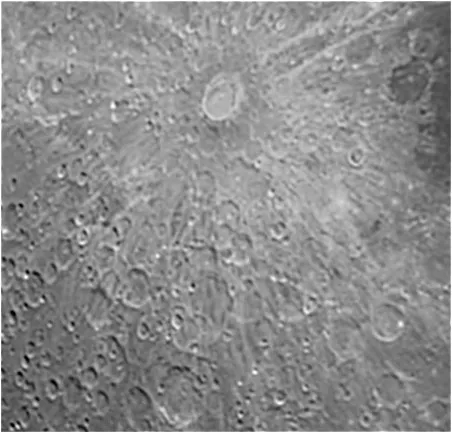

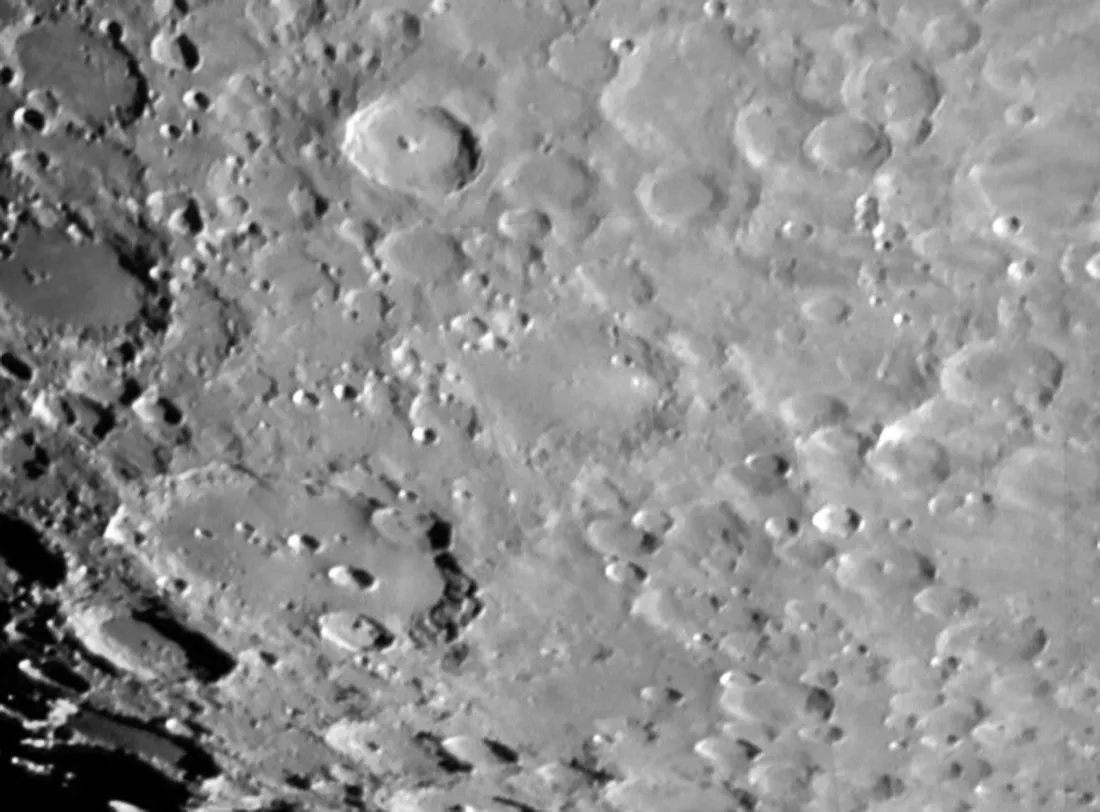

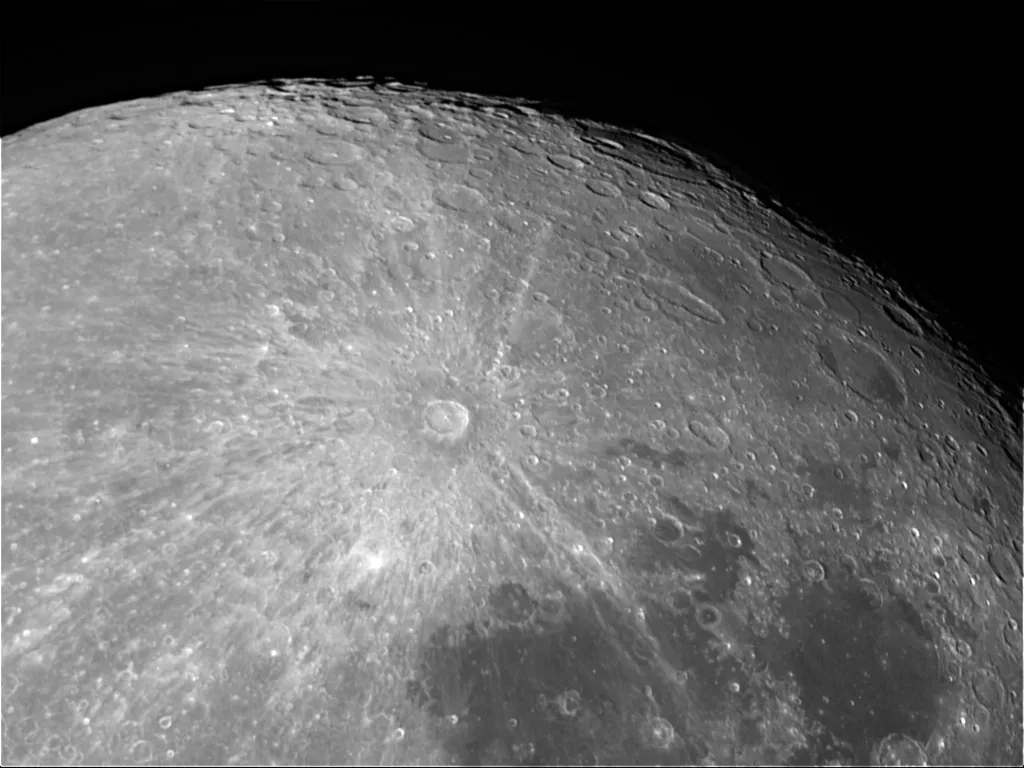

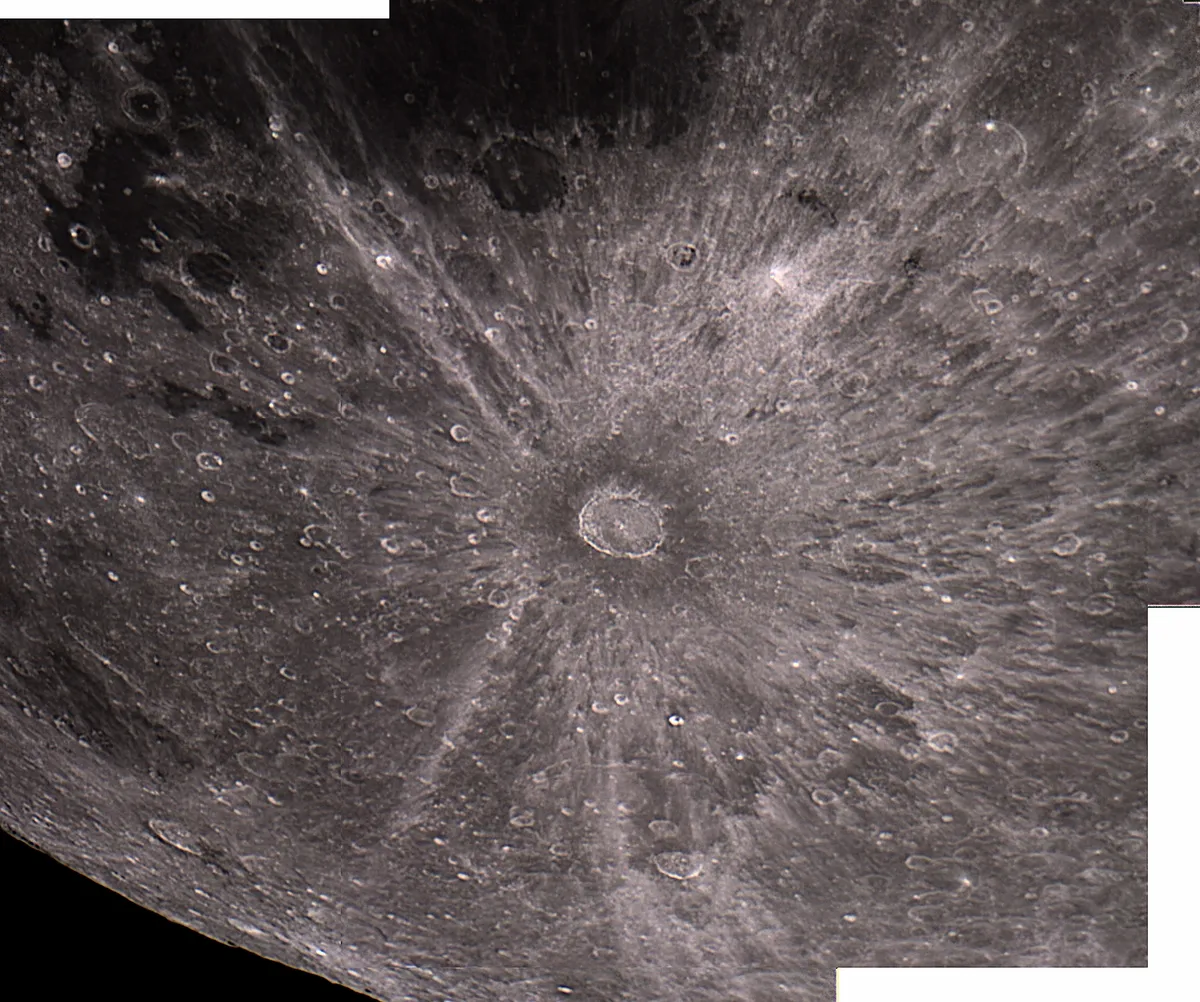

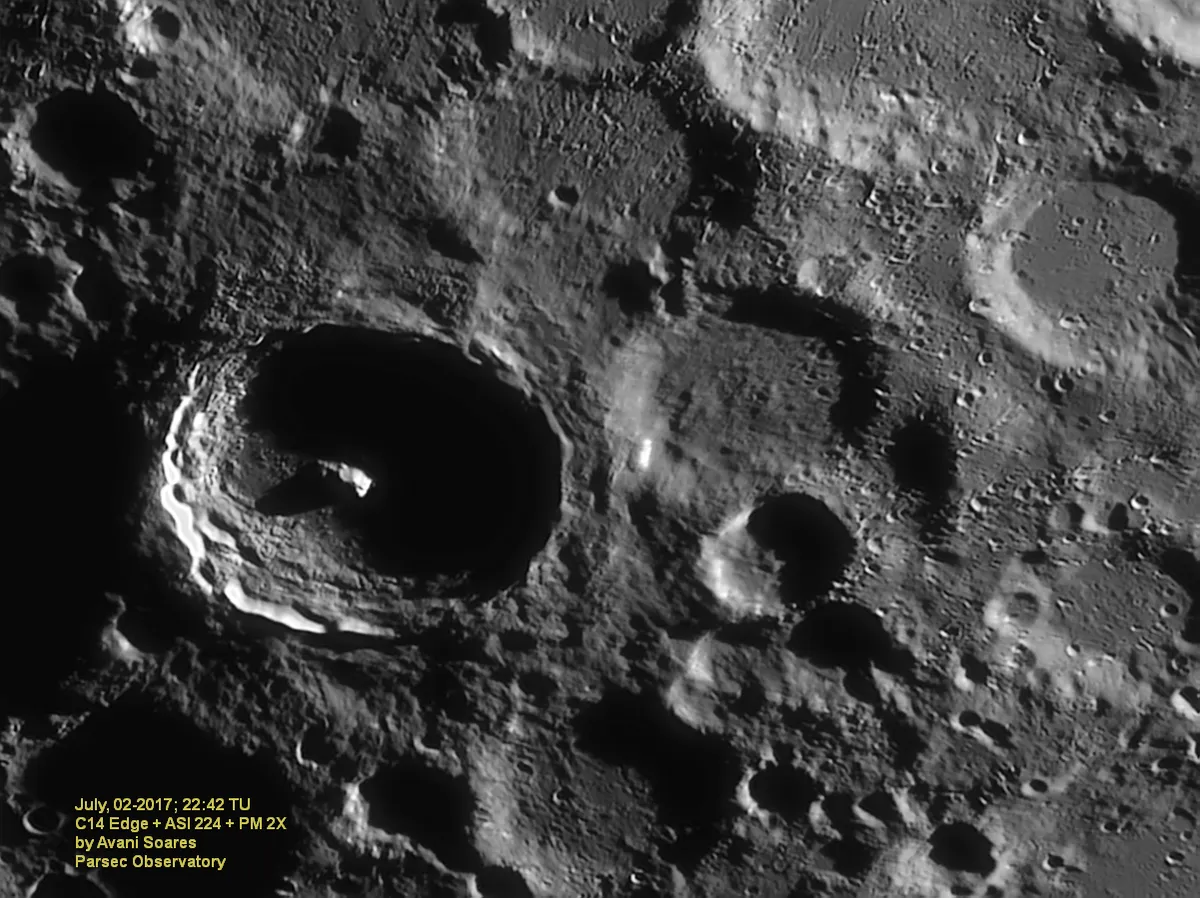

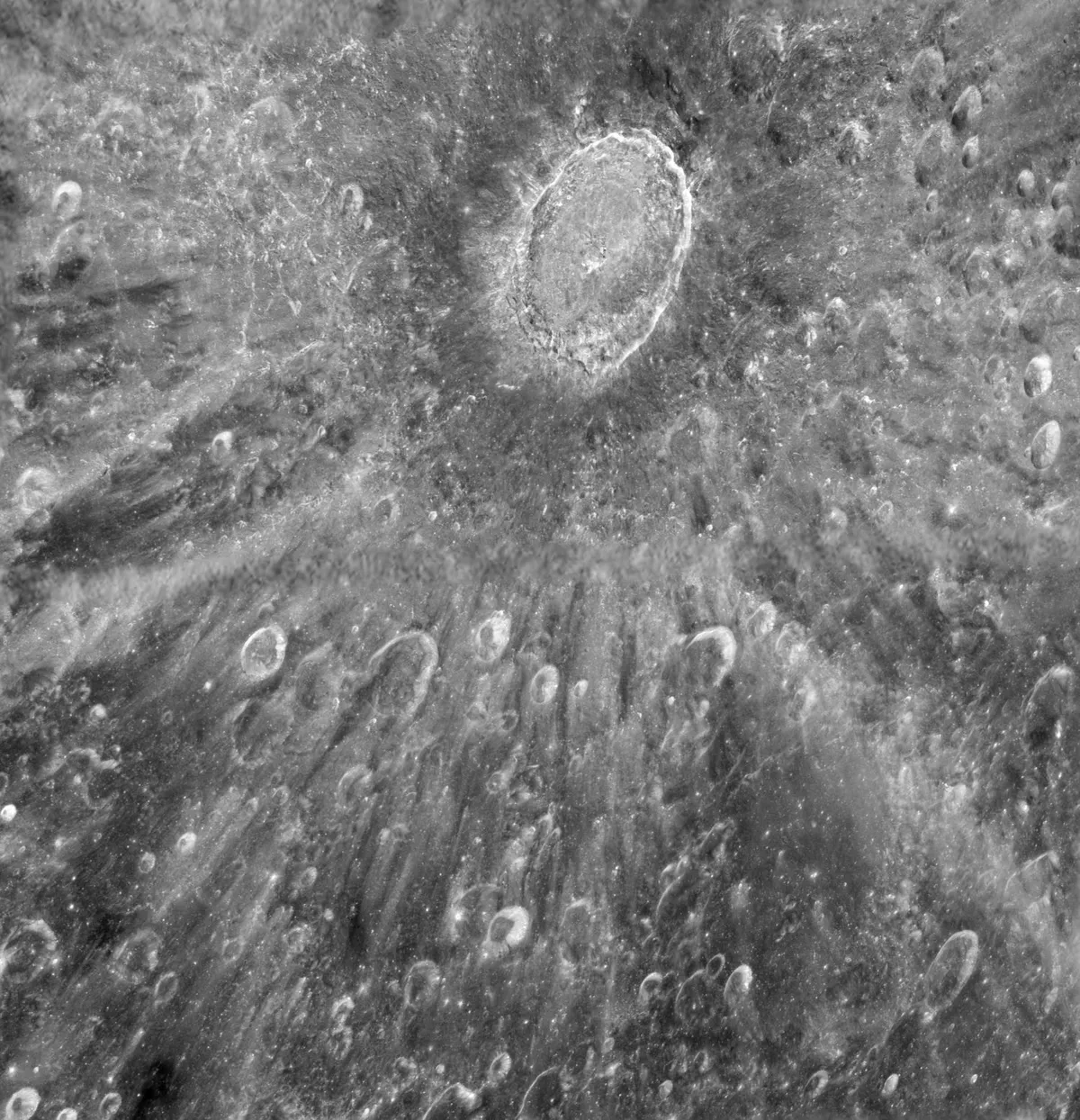

Tycho crater has a high, continuous wall and a prominent central peak, but what distinguishes it is its unrivalled system of bright rays, which extend outward from the crater in all directions, covering an area of over 550,000 square km and containing dense clusters of small secondary craterpits.

Facts about Tycho crater

- Size: 86km

- Age: A little more than 100 million years

- Location: Latitude 43.3°S, longitude 11.2°W

- Recommended observing equipment: 4-inch telescope

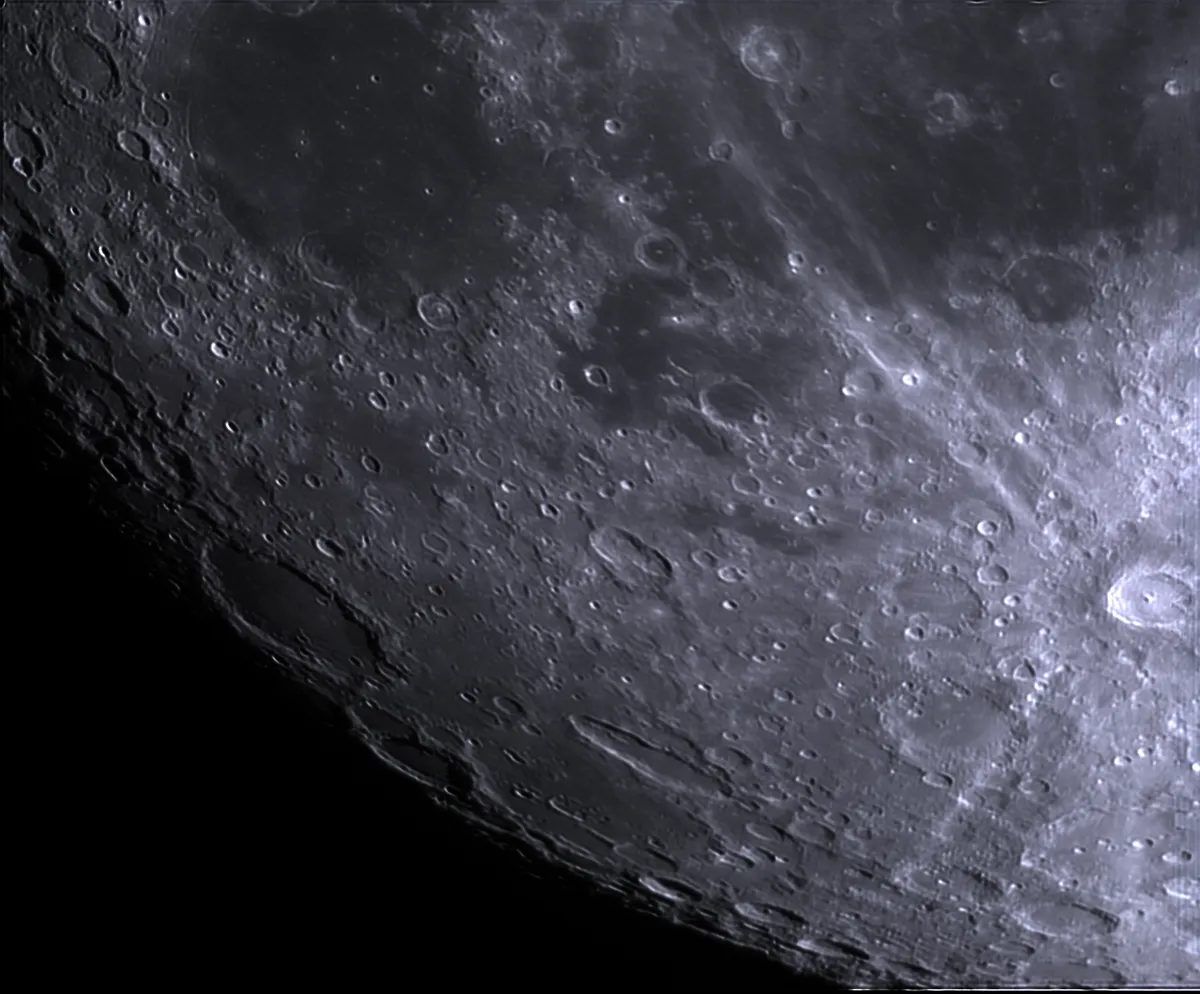

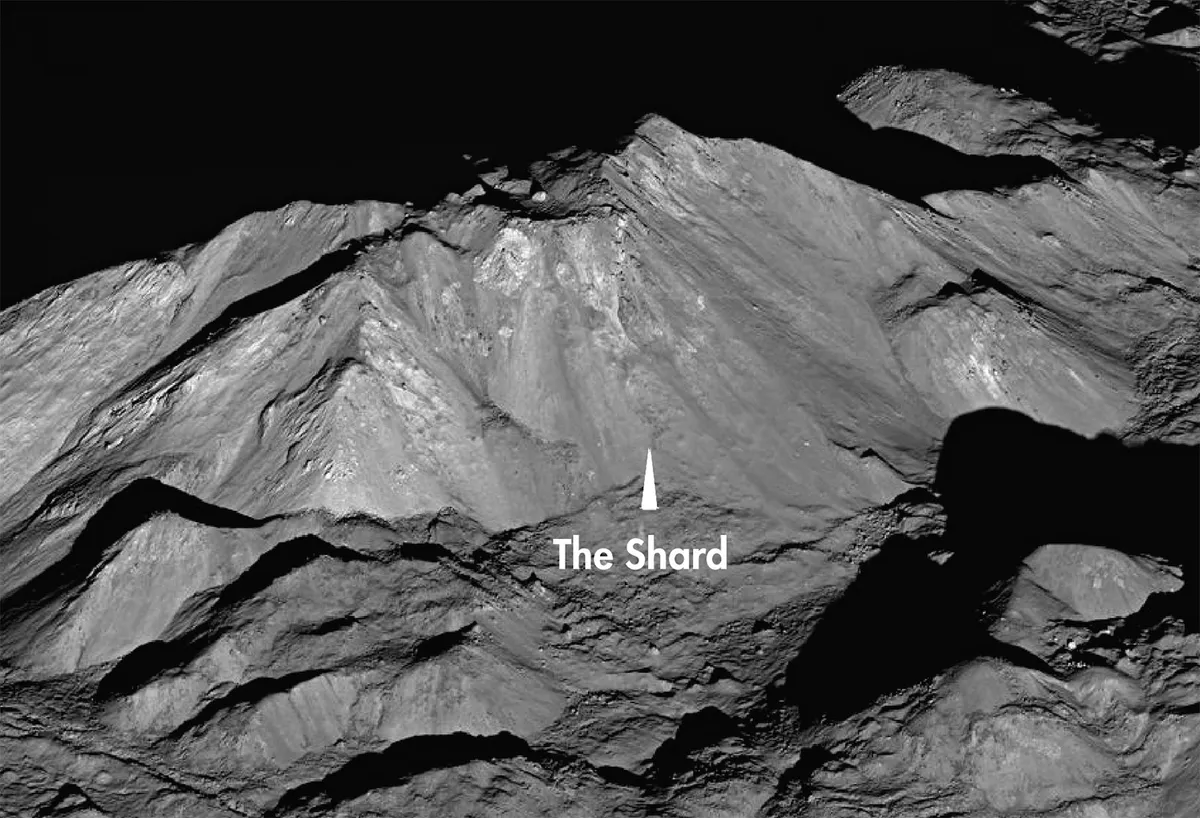

At sunrise Tycho looks like a normal crater, and is a superb sight with its floor partly in shadow and sunlight catching the central peak.

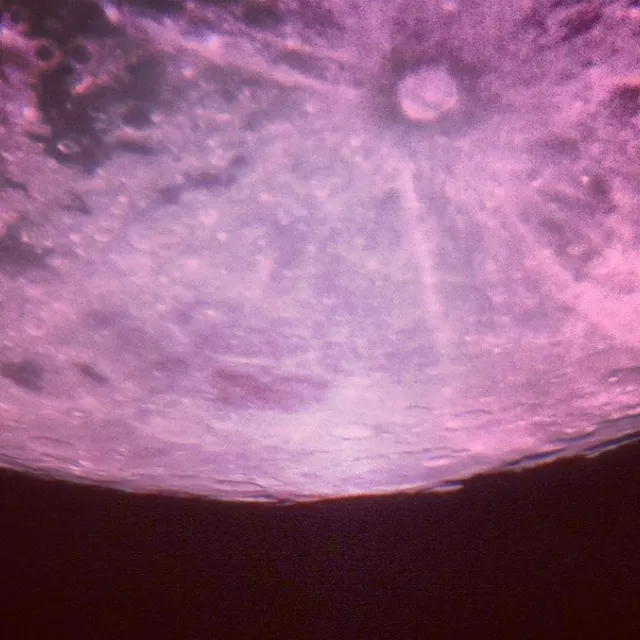

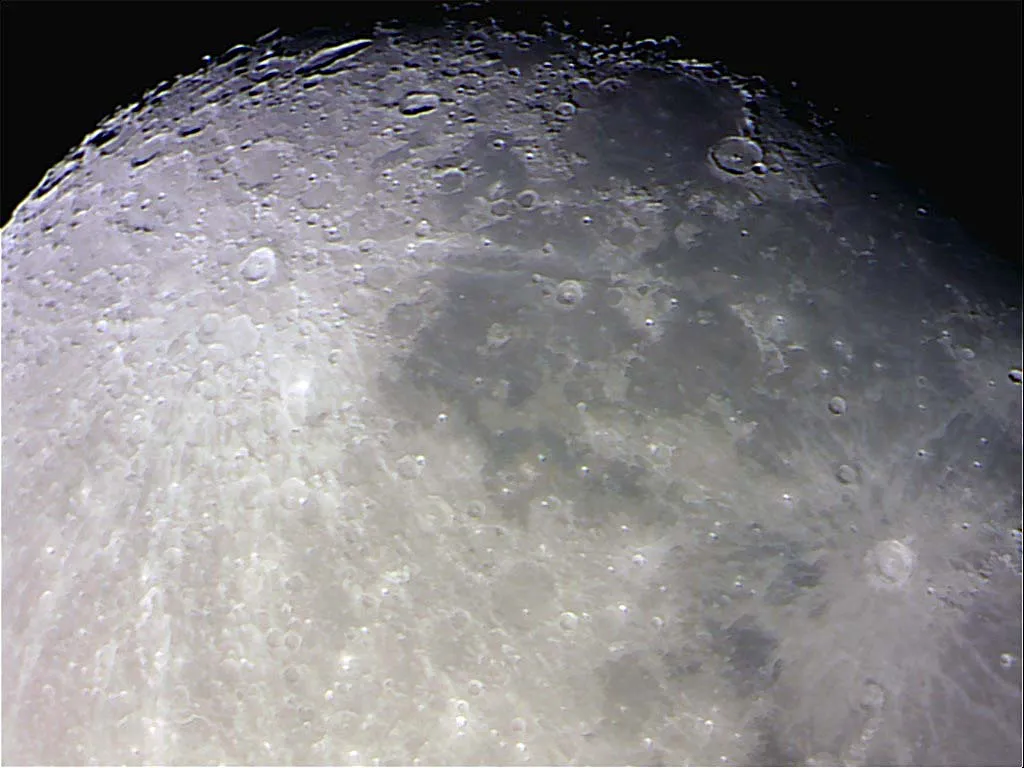

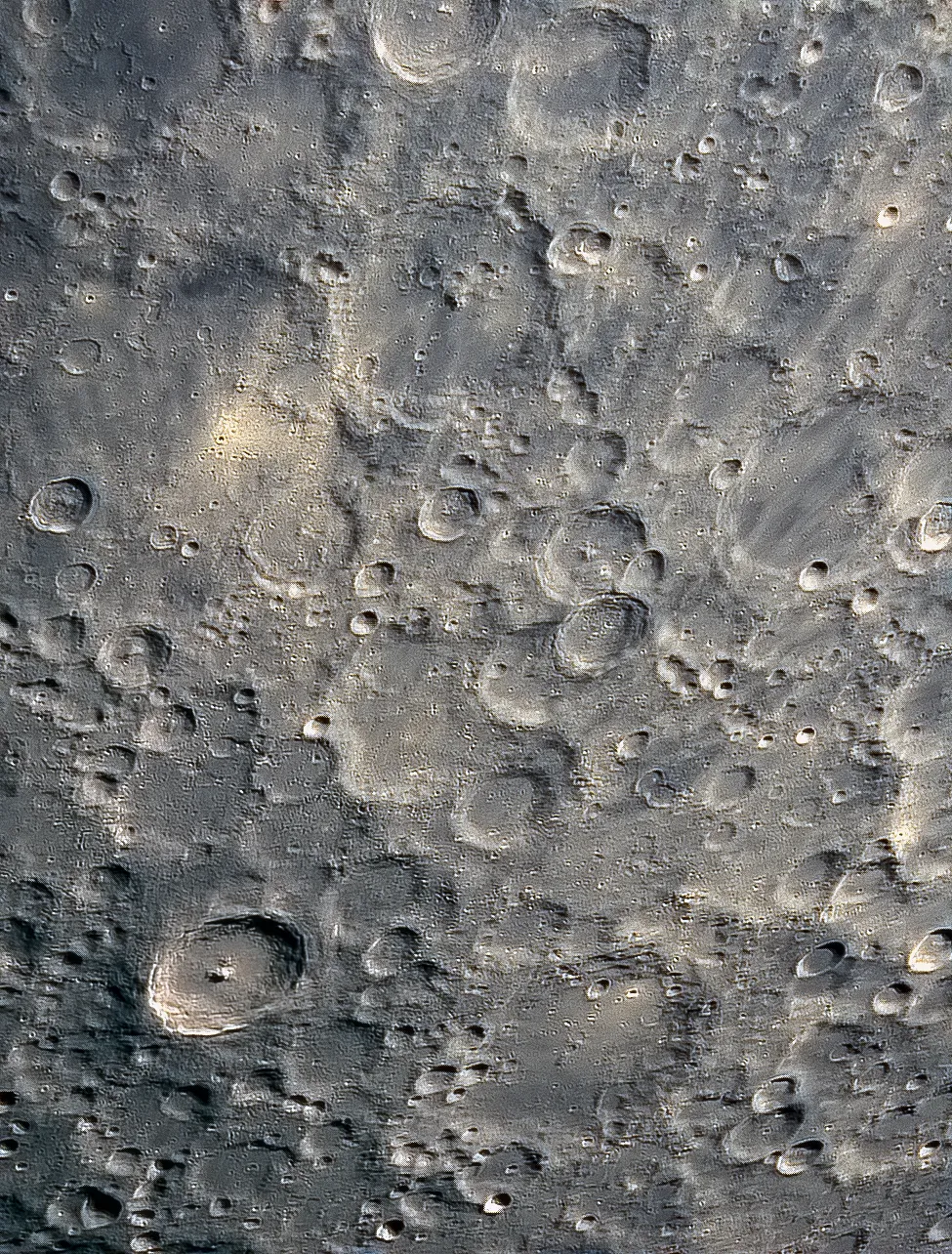

But before long the rays come into view, and near full Moon they dominate the whole scene, covering all the features they cross, and making even large craters difficult to identify.

In fact, full Moon is the worst time for a beginner to start observing. The longest rays stretch for up to 1,500km.

For advice on the best time to take a look at our celestial neighbour, read our guide on how to observe the Moon.

Tycho lies in the southern uplands, and often gives the impression of being a polar crater, though in fact it lies well clear of the libration zone and is only slightly foreshortened.

The fact that the rays of Tycho overlie other features shows that the crater must be very young by lunar standards: perhaps the youngest of all the major craters.Its age is usually given as a little over 100 million years.

Remember, though, that at the time of the Tycho impact the most advanced life forms on Earth were jellyfish and the like.

It has been suggested that the impactor that produced Tycho was a broken-off fragment of the asteroid 298 Baptistina, and even that another fragment produced the Chicxulub crater 65 million years ago and led to the demise of the dinosaurs.

Theories of this kind are interesting, but highly speculative!

Tycho is in a crowded area; nearby large craters are Street, Pictet and Sasserides. However, it is always easy to spot because of its bright walls and regular shape.

When the rays come into view they seem to extend from the walls rather than the peak in the centre.

The ramparts beyond the rim are darker than the floor out to a distance of at least 100km, and are ray-free. This duskier rim may consist of minerals dislodged during the impact.

During the next lunation I strongly recommend that you make a special study of Tycho, both by drawing it and photographing it.

Catch it as the first gleam of sunlight strikes it, and watch the slow emergence of the central peak; then come the rays, so that by the time of the full Moon, everything is swamped in the pool of light.

Below is a selection of images of Tycho Crater captured by astrophotographers and BBC Sky at Night Magazine readers.

For advice on capturing a lunar image, read our guides on how to photograph the Moon and how to draw the Moon. And get to know the lunar calendar with our guide to the phases of the Moon.

To get weekly lunar phases delivered directly to your email inbox, sign up to the BBC Sky at Night Magazine newsletter.

And if you do manage to photograph or sketch the moon, don't forget to send us your images or share them with us via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.