Globular clusters are tightly-packed spherical agglomerations of stars and are thought to be some of the oldest objects in the Universe. ‘Globulars’, as they are sometimes called, are both beautiful and enigmatic star clusters: they can make you slow down to ponder the history and future of the cosmos.

Globular clusters appear to be found in the haloes of most large galaxies, with numbers generally increasing with the size of the galaxy.

For example, giant elliptical galaxy M87 may have more than 10,000 globulars, as compared to the Milky Way’s 160 or so. Some sources say there may be a few more yet to discover in our home Galaxy.

More more guides like this, read our tutorial on deep-sky astronomy, our pick of the best deep-sky objects around Polaris and our guide to deep-sky catalogues.

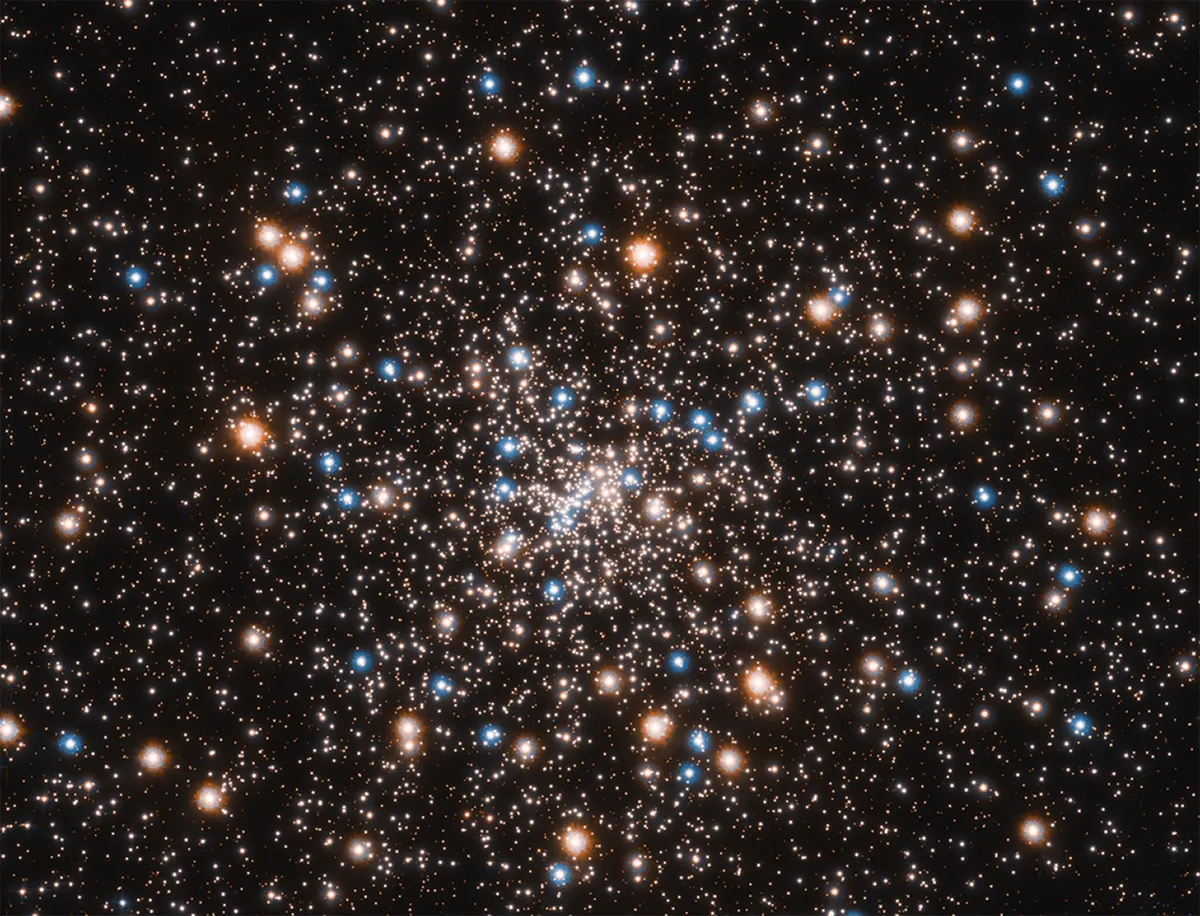

Most globulars contain hundreds of thousands of stars but some, like Omega Centauri, can host millions. We’ve known about globulars for a long time: the first observation was M22 (pictured above), by German astronomer Abraham Ihle in 1665.

Below we'll reveal some of the best globular clusters to view through a telescope in the night sky, and how you can observe them for yourself.

Observing globular clusters

For astronomers, globular clusters look good through any optics and become more impressive with increasing aperture.I always find my eyepiece experience is enhanced when I understand a little about the nature of my observing targets.

The individual stars within globular clusters are rather faint as seen from Earth, so star colour is elusive at the eyepiece.

However, images of globular clusters often show more reddish stars than blue ones. This hints at their great age: often more than 10 billion years.

Their stars are among the oldest in our Galaxy. It can be interesting to compare the eyepiece impression with what can be captured through astrophotography.

Most of the hot blue stars have consumed their hydrogen fuel and dimmed, so the redder stars now dominate.

Some of the blue stars in globulars belong to a group known as ‘blue stragglers’ – blue stars that have persisted longer than most.

Their evolution is thought to be altered as a result of interstellar interactions in a globular’s relatively high star-density environment.

The best-in-class globular clusters are located in the Southern Hemisphere sky, where specimens such as Omega (ω) Centauri and 47 Tucanae outshine any globular visible from mid-northern latitudes.

Where I live in southern Canada, the cold, cloud and snow can make winter observing a challenge, but eventually the temperatures moderate, the clouds part and the snow melts.

That’s when I get my 10- and 20-inch (250mm and 300mm) Dobsonian telescopes out to view my favourite eyepiece targets.

Viewing globular clusters through the eyepiece

Although many of the most-viewed globulars appear visually similar to each other, there are interesting differences between them that are revealed through careful scrutiny.

These will be discussed for individual targets in my globular cluster observing guide below, but let’s begin with some general things to look for when studying globular clusters at the eyepiece.

Most obvious, perhaps, is the variability in size and brightness, both of which depend upon distance, mass and any intervening dust.

Distance rules, of course, and several of the closest and largest globulars are even visible to the naked eye. In the eyepiece under a dark sky, these brighter globulars give the impression of white sugar spilled onto a black velvet tablecloth.

Globular clusters also show different degrees of condensation in their cores, leading astronomers Harlow Shapley (who took part in astronomy's Great Debate of 1920) and Helen Sawyer Hogg to develop a system in the 1920s for classifying globulars from most to least concentrated, using Roman numerals ‘I’ through ‘XII’, respectively.

When I am looking at a globular cluster, I try to discern its shape (round or oval), whether I see any interesting patterns or tendrils of stars, and whether more outlying stars are visible if I increase magnification, thereby also increasing contrast.

Any eyepiece impression is influenced by the surroundings within which an object is set. I enjoy hunting for galaxies near globular clusters – especially the spring globular clusters.

I also enjoy comparing and contrasting the views of globulars that are near each other in the sky.

Some globular clusters seem to occur in groups, although this is mainly a line-of-sight phenomenon rather than them being real ‘clusters of clusters’.This makes them easier to compare, because you don’t need to move your telescope far between targets.

For example, the constellation of Ophiuchus, the Serpent-bearer contains 20 globular clusters that are visible in a 10-to 12-inch (250mm to 300mm) telescope under clear, dark skies.

In one marathon summer observing session, I saw 16 of them through a home-made 16-inch (400mm) reflector, before Ophiuchus set on that crisp, clear August night.

Since many readers of this article will be, like me, located north of latitude 40˚ North, I’ve focused on targets that are easily visible from my locale.

With so many targets to choose from, it’s likely I’ve missed some of your favourite globular clusters, but I hope you’ll enjoy this tour of some of my favourites!

9 globular clusters to see in the sky

M5

The globulars available for viewing come fast and furious by late spring, with M5 being a must on your observing list.

It is easy to star-hop to M5, since it’s located at the western apex of a triangle formed with Alpha (α) Serpentis and Mu (µ) Serpentis.

It’s the brightest northern globular, at mag. +5.8, and one of the largest, so it is spectacular in the eyepiece of any scope. It is hard to discern where this cluster’s edge is, as it seems to fade away into the background sky.

M12

About 9˚ east of M5 and south of the celestial equator you’ll find M12, with M10 about 3.25˚ further east. M10 and M12 appear similar to each other in the eyepiece.

For a very different eyepiece view, have a look at M107. It’s about 9˚ due south of, and half the size of, M10. To my eye it appears to have a more well-defined edge than its larger cousin.

M13

At almost the same right ascension as M12, but far to the north, you’ll find one of the several candidates for best northern globular cluster – M13.

Also known as the Hercules Cluster or the ‘Great Globular’, it is located just outside the longest edge of the Keystone asterism in the constellation of Hercules, the Hero about a third of the way from Eta (η) Herculis to Zeta (ζ) Herculis.

I can just see it with my unaided eye in my Bortle 4 sky on the clearest, darkest nights. It is easy in 10x42 binoculars, pretty in my 6-inch (150mm) reflector, and spectacular in anything bigger.

Southwest of the core there is a feature that looks clearly like a three-vaned propeller in images. It’s harder to see visually, but larger apertures make it more apparent.

If you need a faint fuzzy target after all that brightness, M13 shares a 1˚ field with two galaxies that are within visual range of amateur instruments.

NGC 6207 (above) isn’t too tough to pick out less than a Moon-width northeast of M13.

About halfway between it and M13 is the more challenging IC 4617, which I have occasionally glimpsed as a fuzzy speck in my 20-inch (500mm) reflector. Since my skies are less than perfect, you may be able to spot it with smaller apertures.

M15

In the second half of the year, M15 is a bright globular cluster of magnitude +6.4 that's easy to find from the nose of Pegasus, the Winged Horse.

To locate it, connect the dots from Theta (θ) Pegasi to Epsilon (ε) Pegasi, also known as Enif.

Continue about half the distance along the same line and you should spot M15 in binoculars or a finderscope.

It is one of four globulars known to contain a planetary nebula – Pease 1 – but I’ve never been able to see its mag. +15.5 glow.

M22

In early autumn you can be dazzled by another favourite globular cluster, M22, which is located in Sagittarius, the Archer. If it were higher in the sky, it would rival every cluster mentioned so far.

It is well-resolved in my 10-inch (250mm) reflector, and has an oval appearance in the eyepiece. It is set in the thick of the summer Milky Way, about 2.5˚ northeast of lamda (λ) Sagittarii, the naked-eye star that tops the lid of the Teapot asterism.

M71 is still impressive, but dimmer and smaller than M22, at around 7 arcminutes across. It appears in a field full of stars that enhance the view. Look just southeast of the line joining Gamma (γ) Sagittae and Delta (δ) Sagittae.

M72

Moving to Aquarius, the Water-bearer, let your eyes dark adapt to get the best out of M72, the faintest globular cluster in the Messier Catalogue. It’s located about 3.3˚ south-southwest of Epsilon (ε) Aquarii.

Although all the Messier objects are visible in binoculars, M72 is tough to spot and even harder to appreciate without a larger instrument.

My 10-inch (250mm) reflector at high power shows a fine gravelly texture, but individual stars are not distinct.

M2

For a brighter target in Aquarius, visit M2; it makes an interesting comparison with M15, which is 13˚ to the north, since they’re almost the same size and overall brightness.

While M15 is, in fact, a little brighter, this impression is strongly enhanced for me in small instruments by M15’s much more concentrated core.

NGC 2419

When I look at NGC 2419, the ‘Intergalactic Wanderer’ I get a sense of loneliness and isolation.

Lynx, the Cat, its home constellation, attracts little attention from observers, since it contains no splashy deep-sky objects.

The field within which NGC 2419 lies contains few bright stars. Indeed, it lies at the edge of a region of space known as the ‘Intergalactic Void’ and the cluster has a small, distant appearance.

It can be observed in small refractors, but looks much better at high powers in a larger instrument. Its apparent dimness belies its great intrinsic brightness, which is attenuated by its great distance.

At around 300,000 lightyears, NGC 2419 lies further from Earth than the Milky Way’s satellite galaxies, the Magellanic Clouds.

Globular clusters are fine observing targets regardless of whether you yearn for a faint-fuzzy hunt or would prefer to take in a bright, easy-to-find target.

There are globulars accessible with almost every observing setup, from naked-eye to large-aperture scopes.

Not only do larger scopes reveal more, but the more you look the more you see. You will want to go back to them over and over.

And now with this article complete, I’m off to set up my homemade 10-inch reflector for an evening observing some – you guessed it – globular clusters!