When my husband and I set up our first meteor camera back in 2018, we did it not only to learn more about the orbits of the meteor events we observed and captured with our DSLR cameras, but also to see what we were missing while we slept.

We loved our first meteor camera so much that we soon set up three more and we now have almost full sky coverage.

We had no idea back then just what an important and valuable contribution they would make to so many aspects of meteor and asteroid science.

A meteor is the streak of light we see when a piece of space debris burns up in our atmosphere; a fireball is a meteor that has a magnitude greater than –4.0.

Most fireball meteors are asteroid debris, unlike meteor showers which usually originate from comets (the only exception being the Geminid meteor shower).

The cameras we use to observe meteors are inexpensive CCTV cameras that are capable of capturing low-light images and video.

Although basic, they really pack a punch!

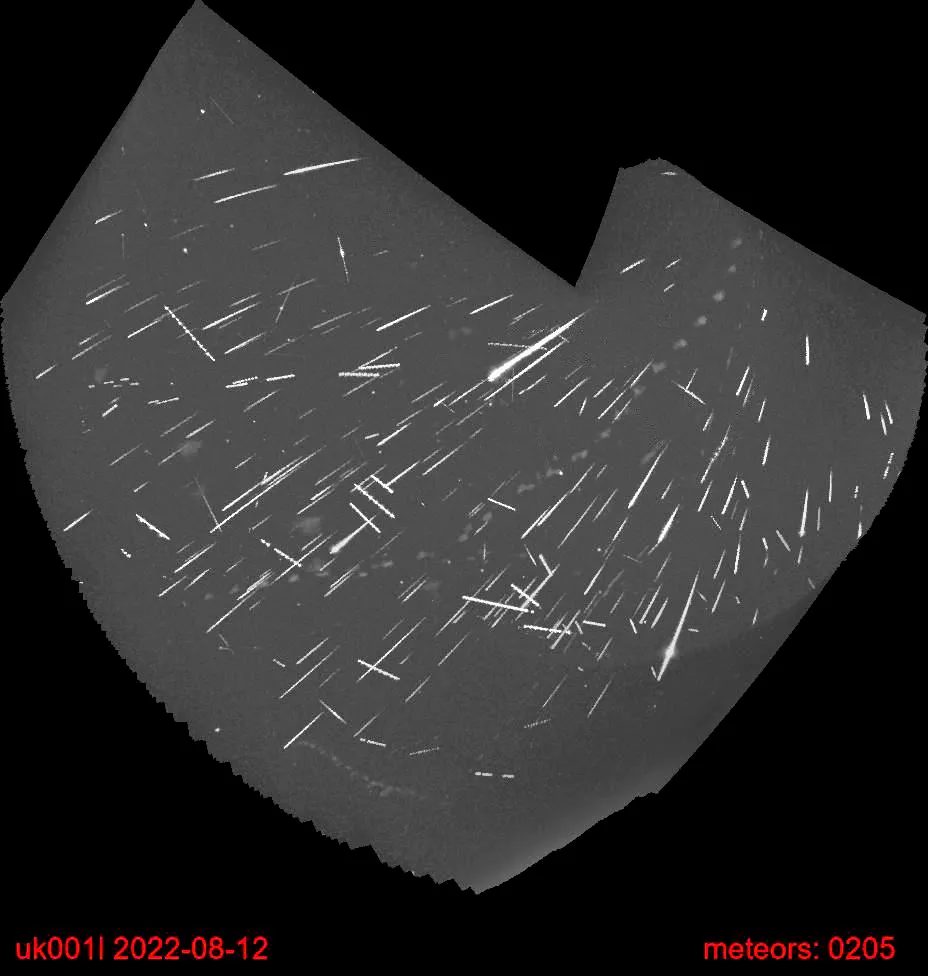

They’re able to detect events down to mag. +6.0 over an approximately 90˚ field of view. They are connected to a Raspberry Pi computer that is running the free, open-source software from the Global Meteor Network (GMN).

You can find out more about how to do this yourself in my guide to setting up a Raspberry Pi meteor detector.

The cameras record from dusk until dawn every night and any potential meteor events are saved.

The following morning, the software uses a machine learning algorithm to eliminate anything that is not a meteor, then the analysis begins.

The data from multiple cameras is combined and if cameras from different locations have detected the same meteor, it can be triangulated.

This means we then have an orbit solution, trajectory, velocity, direction of travel, magnitude and luminous mass estimates for that meteor.

In the UK, all of this data is stored in the UK Meteor Network online archive.

If a fireball meteoroid was large enough to survive and drop meteorites on the ground, scientists use camera data plus computer modelling to calculate a potential fall zone.

Putting the CCTV meteor detector to test

On 28 February 2021, a mag. –7.9 fireball was seen by thousands of people across the UK and it was captured on several meteor cameras, including ours.

The view from our camera was head-on to the fireball so it was impossible to get any trajectory analysis from it.

Luckily, other cameras got a much better view of it (this is why we need lots of cameras!) and the data from six camera networks resulted in the recovery of a pristine carbonaceous chondrite meteorite.

This was the first witnessed meteorite fall in the UK for 30 years and it was incredible to be a part of that.

Also thanks to meteor camera data, meteorites were recovered from the northern coast of France after the impact of the one-metre diameter asteroid 2023 CX1 on 13 February 2023.

Approximately 65,000 meteorites have been found on Earth, but we only know the original orbits of about 50 of them.

Data from the camera networks is giving us that valuable information.

Worldwide data from the Global Meteor Network gives us accurate meteor rates and has even resulted in the discovery of new meteor showers.

NASA and ESA are also using the data to help keep spacecraft and astronauts safe.

It’s incredible how much important science is being done with these little CCTV cameras, and we love being part of this citizen science project.

The videos and images from the cameras are awesome for outreach and it’s exciting because you never know when the next interesting event will occur.

This article originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.