Here in the Northern Hemisphere, Christmas festivities and other celebrations help many of us to get through the bleak midwinter, when all is darkness and gloom, bitter cold and frosty wind.

But at the South Pole the festive period falls in the Antarctic summer, during the short work and tourist season.

Down there it’s not until after New Year that the days begin to rapidly shorten, when all the fair-weather Antarcticans wave goodbye to the continent for warmer climes.

What’s left are a thousand or so people that form skeleton crews for Antarctica’s 70 permanent research stations.

Find out about the Antarctic Search for Transiting ExoPlanets, or lessons on isolation from the ESA doctor who braved Antarctica.

These hardy souls are known as ‘winterovers’.

Largely confined to their stations due to the extreme cold, biting wind and permanent darkness outside, winterovers can experience isolation and claustrophobia, infighting with crewmates, and can even have trouble perceiving the passage of time.

To combat these challenges and boost morale, in 1902 the British explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott and his men planned a faux Christmas celebration on 21 June, which they called Midwinter Day.

The day has since been embraced as a unique holiday, replete with its own traditions and events.

Some stations plan a week of activities, others make gifts on an Antarctic theme from materials found on base, and all stations have a slap-up meal and send each other digital Midwinter greeting cards.

"The isolation does get to everyone after a while on one level or another, so it’s good to have something to look forward to," says John Hardin, who spent two Christmases at the South Pole and winterovered for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station in 2019/20.

"It’s a quieter thing, but Midwinter feels a little more meaningful to everybody – it’s the holiday of Antarctica."

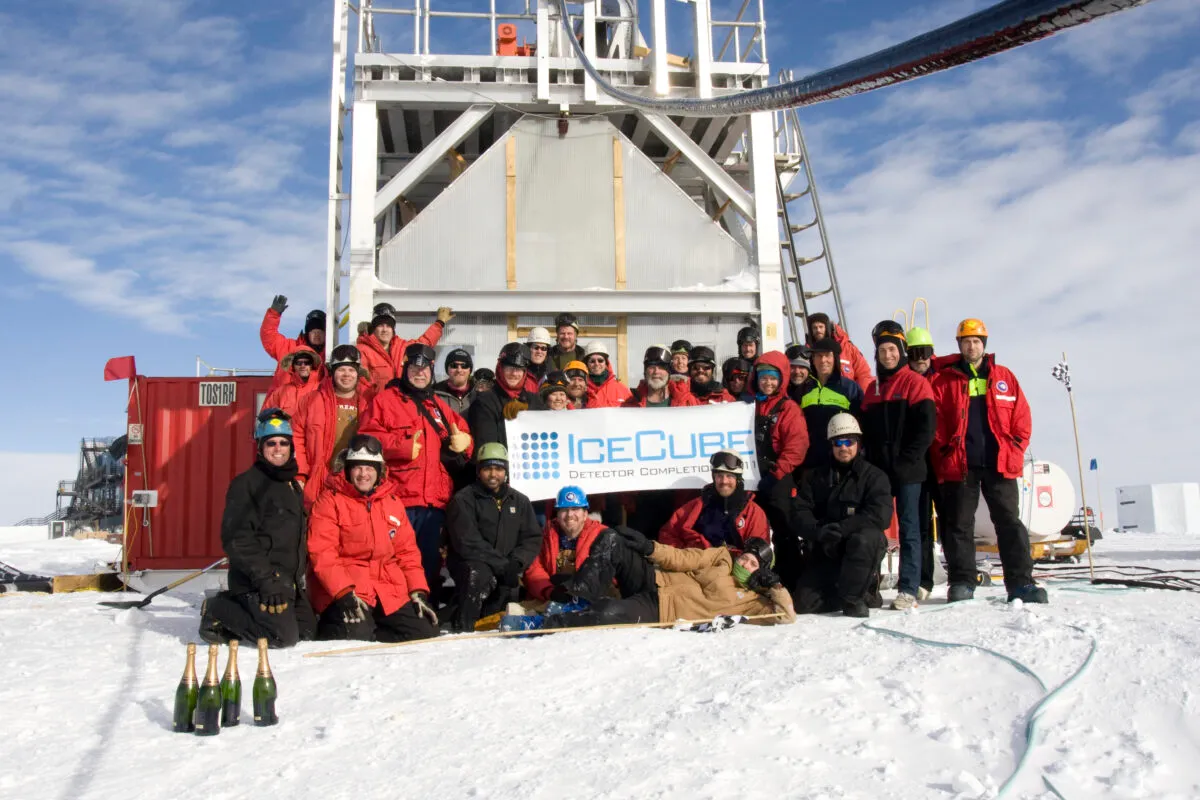

Winterover veterans Moreno Baricevic and Wenceslas Marie-Sainte were in charge of maintaining the unique IceCube Observatory this year, which is actually an experiment consisting of 5,160 detectors buried in a cubic kilometre of ice.

Designed to pick up traces of rare neutrino interactions with matter, it helps scientists understand the cosmic origins of these nearly massless fundamental particles.

"We maintain IceCube’s sensors, the huge amount of cables coming from them, and the IceCube Laboratory, where we have more than 100 computers that collect, process, filter and then send all the meaningful data up north in real time," says Baricevic on a videocall, sitting alongside Marie-Sainte, near the end of their 11-month stint at the Pole.

Working 24/7 and facing the same deprivations that Captain Scott and his men faced 120 years before, for the two researchers Midwinter is always a welcome pause.

"We celebrate the fact that we as a community are passing those difficult days together," says Marie-Sainte, before Baricevic adds: "It’s something that is very sacred."

The duo will be back in Italy and France by now, enjoying everything they had missed while away – which for Marie-Sainte includes riding his bike in the rain and having "a really good Belgian beer".

But when 21 June rolls around, they will celebrate Midwinter again, a moment of pause and reflection upon their life-changing experience on the untouched continent.

This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.