On seeing a chart of the Southern Hemisphere constellations, the Lick Observatory astronomer Heber Doust Curtis is reputed to have declared: “It looks like somebody’s attic!”.

While it’s true that the southern hemisphere constellations include such technological relics as an air pump, a chemical furnace and a pendulum clock, there are also exotic animals such as a peacock, a bird of paradise and a dorado chasing a flying fish.

Not to mention the oak tree that was planted by Edmond Halley to commemorate King Charles II, only to be later felled by a Frenchman.

Read our astronomy guide to the Southern Hemisphere and find out what you can see in the Southern Hemisphere night sky tonight.

Find out which constellations are visible in the Southern Hemisphere all year round in our guide to circumpolar constellations.

Before the first European seafarers ventured around the tip of Africa to open trade routes to India and the Far East, the sky around the south celestial pole was a blank slate for Western astronomers.

The 48 Greek constellations in Ptolemy’s book the Almagest of 150 AD went only as far south as Centaurus and Argo Navis.

Beyond that lay the celestial equivalent of terra incognita, beneath the horizon for European observers.

26 southern hemisphere constellations

Constellations introduced by Keyser, de Houtman and Plancius in 1596–1603

- Apus - Bird of paradise

- Chamaeleon - Chameleon

- Dorado - Goldfish (dolphinfish)

- Grus - Crane

- Hydrus - Little water snake

- Indus - Indian

- Musca - Fly

- Pavo - Peacock

- Phoenix - Phoenix

- Triangulum Australe - Southern Triangle

- Tucana - Toucan

- Volans - Flying fish

Constellations introduced by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in 1754

- Antlia - Air pump

- Caelum - Chisel

- Circinus - Compasses

- Fornax - Furnace

- Horologium - Pendulum clock

- Mensa - Table (after Table Mountain)

- Microscopium - Microscope

- Norma - Set square

- Octans - Octant

- Pictor - Painter's easel

- Pyxis - Compass

- Reticulum - Net

- Sculptor - Sculptor's studio

- Telescopium - Telescope

Exploring the southern sky

One man was determined to fill in this blank area of sky: the Dutch cartographer and theologian Petrus Plancius (1552–1622).

When the first Dutch trading expedition to the East Indies, the Eerste Schipvaart, set sail in April 1595, Plancius instructed several members of the ships’ crews to make positional observations of the southern stars.

Foremost among these trusted observers was Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser (c1540–96), chief navigator on the Hollandia, joint-largest of the four ships in the fleet.

The Dutch fleet arrived at Madagascar, latitude 23˚ south, in September 1595 where they remained for several months to resupply and recover from scurvy and malnutrition.

It was during this stopover that Keyser made most of his observations, measuring star positions from the crow’s nest of his ship, probably using an astrolabe given to him by Plancius.

Resuming their voyage, the expedition eventually reached the island of Sumatra in June 1596 before moving on to their final destination of Bantam (now Banten) in Java, where Keyser died.

According to a contemporary account, he died while observing from the crow’s nest, although the cause is not stated.

Fortunately, his legacy did not die with him. When the depleted fleet returned to the Netherlands in August 1597 with its precious cargo of spices from the East, they carried with them another, more lasting treasure: Keyser’s observations of the southern stars.

These were duly delivered to Plancius.

Keyser's 12 southern hemisphere constellations

Keyser’s stars, divided into 12 new constellations, first appeared on a celestial globe made by Plancius in 1598, and again two years later on a globe by his colleague Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612).

These constellations were the first significant additions to the sky since Ptolemy’s time.

There were 122 stars in the 12 constellations, plus five more stars that formed a southern extension of Eridanus, and 12 ‘unformed’ stars that were not part of any constellation.

Whether Keyser observed more stars than this we do not know, because his original records are long lost.

Who actually invented these 12 new southern figures?

It was probably not Keyser, since he would not have had a chance to do so before his untimely death.

Some historians believe they were invented by Plancius after receiving Keyser’s observations.

But there is another candidate: Frederick de Houtman (1571–1627), younger brother of the commander of the Dutch fleet, Cornelis de Houtman (1565–99).

Frederick was also a crew member of the Eerste Schipvaart and made celestial observations of his own, independently of Keyser.

After Keyser died, Frederick would have had access to his records.

We can imagine him whiling away the time on the long voyage home by collating the joint observations and grouping them into constellations representing the wondrous things they had seen.

It seems fair to assign credit for the invention of these new Southern Dozen constellations jointly to Keyser and de Houtman, and their mentor Plancius.

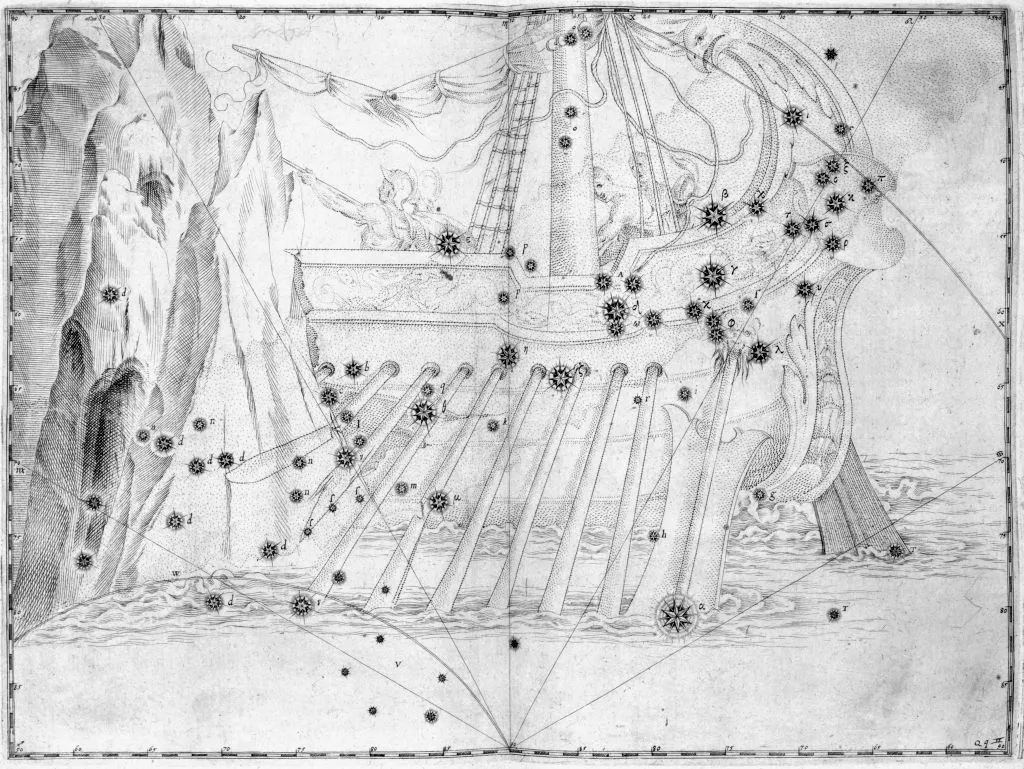

Bayer’s southern star chart

The new southern constellations made their first appearance in print, as distinct from on a globe, in the great star atlas Uranometria in 1603 by the German astronomer Johann Bayer.

Bayer devoted one plate to each of the 48 Ptolemaic constellations, but in addition he gave the new Southern Dozen a separate 49th chart of their own, creating the first all-sky star atlas.

For European astronomers at the start of the 17th century, Bayer’s chart of this hitherto invisible area of sky must have been as much of a revelation as the first photographs of the far side of the Moon were in more recent times.

Since globes were expensive, few people ever saw them. By contrast, Bayer’s atlas was widely circulated.

His Chart 49 was the first time that most astronomers found out about the new constellations, and as a result he was often wrongly credited as their inventor.

In addition, Bayer’s southern chart showed the two Magellanic Clouds, labelled Nubecula Major and Nubecula Minor, as well as the first record of 30 Doradus (the Tarantula Nebula) and the globular cluster 47 Tucanae.

De Houtman’s star catalogue

Seven months after their return from the Eerste Schipvaart, the de Houtman brothers set off again to the East Indies.

In 1599 they reached Aceh in northern Sumatra.

There Cornelis was killed in a dispute fomented by rival Portuguese traders and Frederick was imprisoned for two years by the Sultan of Aceh until a ransom was paid for his release.

During his time in captivity, de Houtman studied the local Malay language and added to the southern stars he and Keyser had observed on the first voyage.

On his return to Holland in 1603, he published his observations as an appendix to a Malay and Madagascan dictionary that he had compiled, surely one of the most unlikely pieces of astronomical publishing in history.

De Houtman’s catalogue lists 304 stars, of which 111 lay in the new Southern Dozen constellations.

The remainder had either already been listed by Ptolemy or were additions to the Ptolemaic constellations, notably Argo Navis and Centaurus.

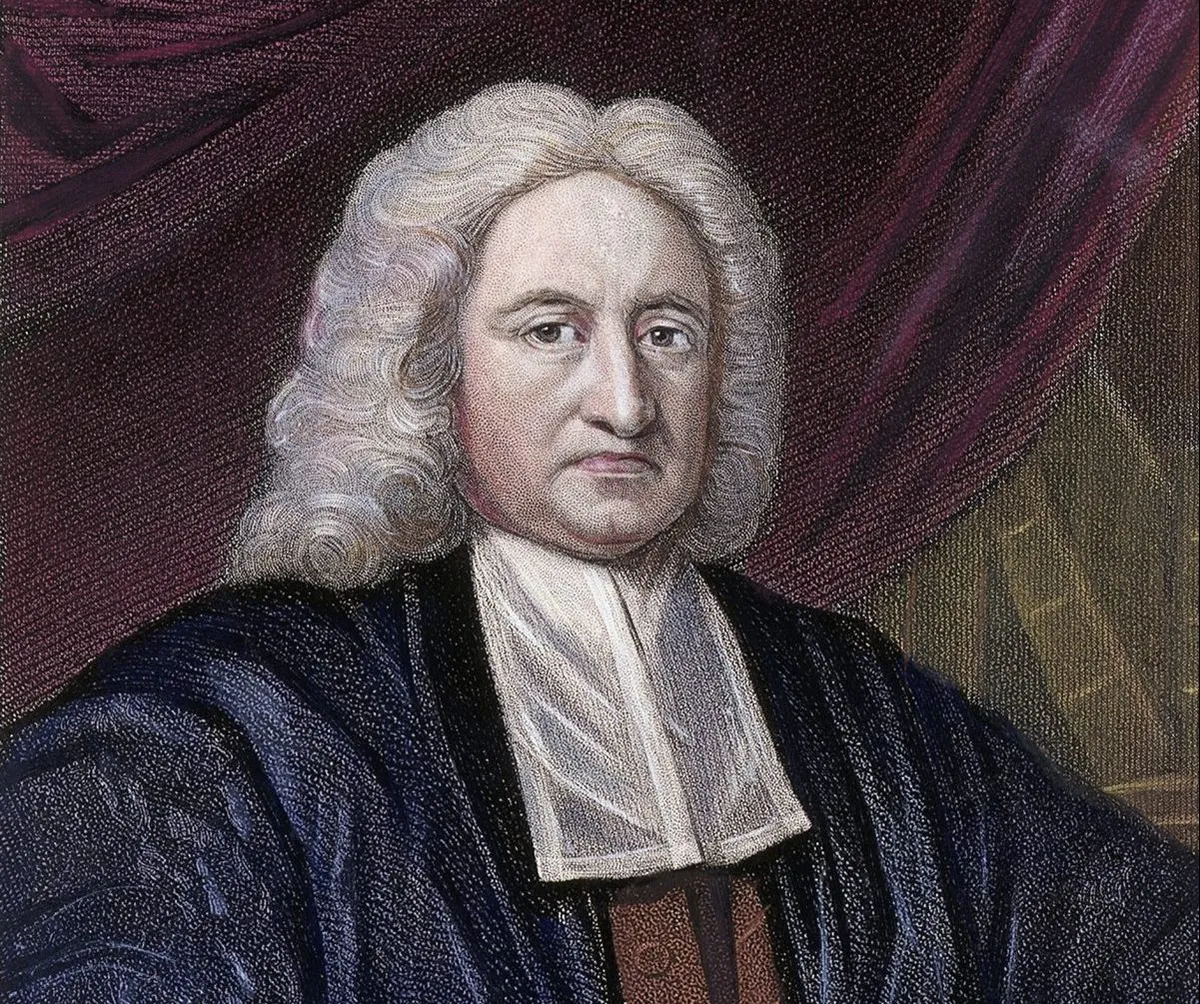

Halley heads south

There things stood for 75 years, until the 20-year-old Edmond Halley (1656–1742) set out for the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic.

His intention was to produce a southern extension to the star catalogue being prepared at Greenwich by his mentor John Flamsteed (1646–1719), the first Astronomer Royal.

He took with him a large sextant with telescopic sights, a smaller quadrant, a pendulum clock and a number of refracting telescopes, all paid for by his wealthy father.

He set these up in a small stone building on a ridge now called Halley’s Mount, near the centre of the island.

What he had not anticipated was the weather, which was far cloudier than he had hoped, allowing no more than an hour’s observing per night.

Even when it was clear, he complained that his instruments and notebook rapidly became soaked with dew.

Halley spent just over a year observing on St Helena, from early February 1677 to late February 1678.

On his return to England he was quick to get his results into print, starting with a star chart that was printed by July 1678.

His accompanying catalogue, Catalogus Stellarum Australium, was published in early 1679.

It contained 341 stars, far fewer than he must have hoped for when he set out.

Halley adopted the Southern Dozen constellations invented by Keyser and de Houtman, and also added a new one of his own: Robur Carolinum – Charles’s Oak, to commemorate the tree in which Charles II of England had hidden to escape the Parliamentary forces after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester in 1651.

Halley formed it from stars that had previously been part of Argo Navis, the ship of the Argonauts.

Among its stars was the peculiar variable star we now know as Eta Carinae.

The overall accuracy of Halley’s catalogue was restricted by errors in the positions of his reference stars, for which he relied on Tycho Brahe’s observations.

Flamsteed’s assistant Abraham Sharp (1653–1742) later recalculated the coordinates of Halley’s stars using Flamsteed’s improved positions for the reference stars, and published the results in 1725 as a supplement to Flamsteed’s posthumous Catalogus Britannicus, thereby turning that work into the first all-sky catalogue.

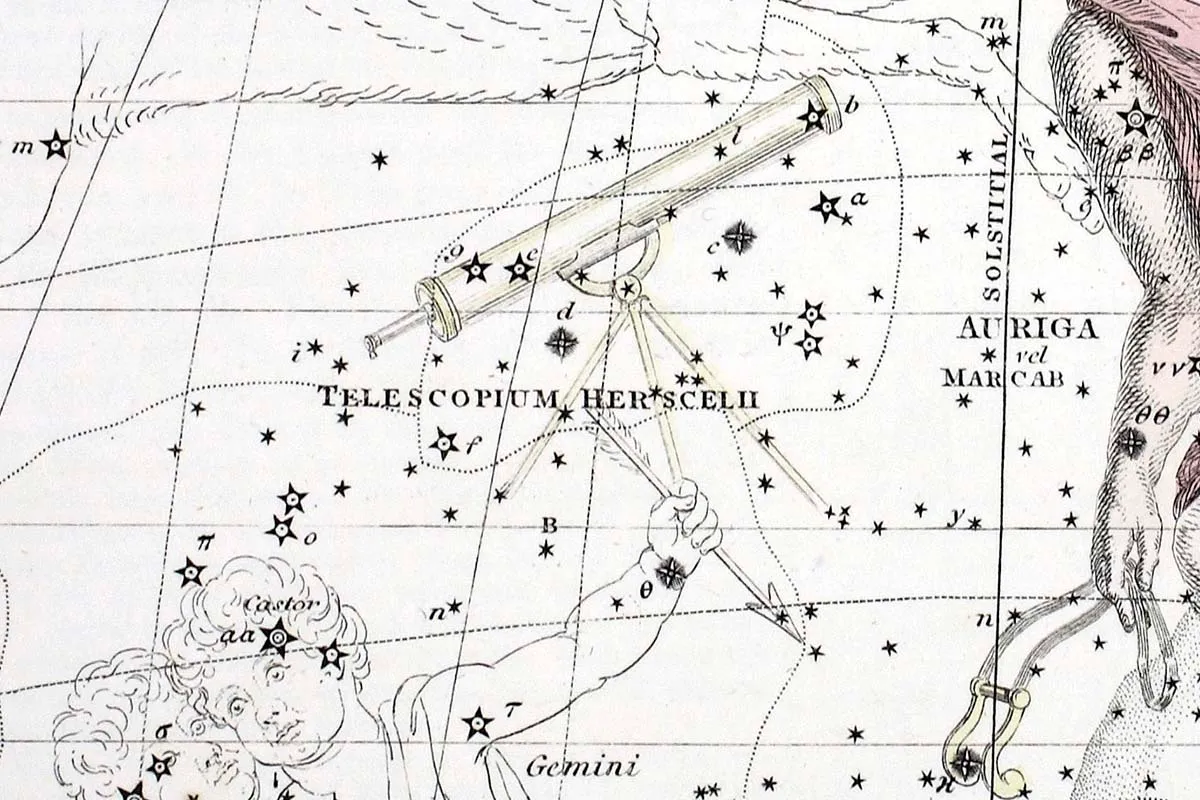

The French collection

Even with the Southern Dozen constellations now firmly established, there were still yawning gaps between them.

These were filled by a French astronomer, Nicolas Louis de Lacaille (1713–62), who is largely responsible for arranging the southern sky into the way we see it today.

In 1750, Lacaille sailed from France to South Africa where he set up a small observatory at the Cape of Good Hope (not yet known as Cape Town) under the famous Table Mountain.

From August 1751 to July 1752, he measured the positions of some 9,800 stars between the Tropic of Capricorn and the south celestial pole using a telescope of a mere 13.5mm (half an inch) aperture mounted on a 3-foot quadrant.

To accommodate these stars, he created 14 new constellations.

Whereas the Dutch explorers had mostly named their constellations after exotic animals, Lacaille commemorated instruments of science and the arts, the exception being Mensa which he named after the Table Mountain under which he had carried out his observations.

As well as these new creations, he uprooted Halley’s Robur Carolinum, evidently considering an homage to an English king an inappropriate addition to the southern sky.

On his return to France in 1754, Lacaille presented the French Royal Academy of Sciences with a chart of the southern heavens containing these new constellations.

An engraved version was published two years later in their Mémoires, along with a preliminary catalogue of stars.

His final catalogue, containing 1,942 entries down to sixth magnitude, was published posthumously in 1763 under the title Coelum Australe Stelliferum, accompanied by a revised map with the names of his new constellations in Latin (the original names had all been in French).

In addition to inventing 14 new figures, Lacaille also divided the unfeasibly large Greek constellation of Argo Navis into three parts: Carina, the keel or body; Puppis, the poop (stern); and Vela, the sails.

Were the three parts to be reunited, the resulting figure would be over 25% larger in area than the current largest constellation, Hydra (whose brightest star is Alphard).

It is sometimes said that Pyxis, the mariner’s compass, was a fourth subdivision of Argo, but in fact it was one of Lacaille’s own inventions.

In 1844, John Herschel, who knew the southern sky well after four years observing at the Cape, proposed replacing Pyxis with Malus, representing the mast of Argo, but it was Lacaille’s invention that stuck.

In fact, no further constellations were added to either the northern or southern skies after Lacaille’s time.

Today, when we look at the southern sky, we see not so much “somebody’s attic” but the results of over 150 years of endeavour.

The southern constellations stand as a monument to those ancient explorers and astronomers who helped fill in our knowledge of the sky.

This guide originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.